Neil Gaiman - Odd and the Frost Giants

Here you can read online Neil Gaiman - Odd and the Frost Giants full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Odd and the Frost Giants

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Odd and the Frost Giants: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Odd and the Frost Giants" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Odd and the Frost Giants — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Odd and the Frost Giants" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

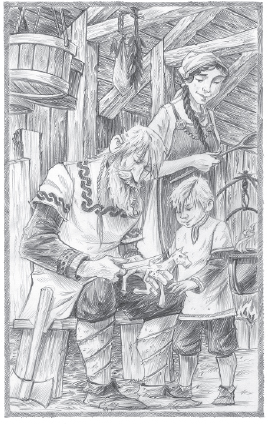

Illustrated by

Brett Helquist

For Iselin and Linnea

T HERE WAS A BOY called Odd, and there was nothing strange or unusual about that, not in that time or place. Odd meant the tip of a blade , and it was a lucky name.

He was odd, though. At least, the other villagers thought so. But if there was one thing that he wasnt, it was lucky.

His father had been killed during a sea raid two years before, when Odd was ten. It was not unknown for people to get killed in sea raids, but his father wasnt killed by a Scotsman, dying in glory in the heat of battle as a Viking should. He had jumped overboard to rescue one of the stocky little ponies that they took with them on their raids as pack animals.

They would load the ponies up with all the gold and valuables and food and weapons that they could find, and the ponies would trudge back to the longship. The ponies were the most valuable and hardworking things on the ship. After Olaf the Tall was killed by a Scotsman, Odds father had to look after the ponies. Odds father wasnt very experienced with ponies, being a woodcutter and wood-carver by trade, but he did his best. On the return journey, one of the ponies got loose during a squall off Orkney and fell overboard. Odds father jumped into the grey sea with a rope, pulled the pony back to the ship and, with the other Vikings, hauled it back up on deck.

He died before the next morning of the cold and the wet and the water in his lungs.

When they returned to Norway, they told Odds mother, and Odds mother told Odd. Odd just shrugged. He didnt cry. He didnt say anything.

Nobody knew what Odd was feeling on the inside. Nobody knew what he thought. And, in a village on the banks of a fjord, where everybody knew everybodys business, that was infuriating.

There were no full-time Vikings back then. Everybody had another job. Sea raiding was something the men did for fun or to get things they couldnt find in their village. They even got their wives that way. Odds mother, who was as dark as Odds father had been fair, had been brought to the fjord on a longship from Scotland. She would sing Odd the ballads that she had learned as a girl, back before Odds father had taken her knife away and thrown her over his shoulder and carried her back to the longship.

Odd wondered if she missed Scotland, but when he asked her, she said no, not really, she just missed people who spoke her language. She could speak the language of the Norse now, but with an accent.

Odds father had been a master of the axe. He had a one-room cabin that he had built from logs deep in the little forest behind the fjord, and he would go out to the woods and return a week or so later with his handcart piled high with logs, all ready to weather and to split, for they made everything they could out of wood in those parts: wooden nails joined wooden boards to build wooden dwellings or wooden boats. In the winter, when the snows were too deep for travel, Odds father would sit by the fire and carve, making wood into faces and toys and drinking cups and bowls, while Odds mother sewed and cooked and, always, sang.

She had a beautiful voice.

Odd didnt understand the words of the songs she sang, but she would translate them after she had sung them, and his head would roil with fine lords riding out on their great horses, their noble falcons on their wrists, brave hounds always padding by their sides, off to get into all manner of trouble, fighting giants and rescuing maidens and freeing the oppressed from tyranny.

After Odds father died, his mother sang less and less.

Odd kept smiling, though, and it drove the villagers mad. He even smiled after the accident that crippled his right leg.

Odds father would sit by the fire and carve, making wood into faces and toys and drinking cups and bowls.

It was three weeks after the longship had come back without his fathers body. Odd had taken his fathers tree-cutting axe, so huge he could hardly lift it, and had hauled it out into the woods, certain that he knew all there was to know about cutting trees and determined to put this knowledge into practice.

He should possibly, he admitted to his mother later, have used the smaller axe and a smaller tree to practise on.

Still, what he did was remarkable.

After the tree had fallen on his foot, he had used the axe to dig away the earth beneath his leg and he had pulled it out, and he had cut a branch to make himself a crutch to lean on, for the bones in his leg were shattered. And, somehow, he had got himself home, hauling his fathers heavy axe with him, for metal was rare in those hills and axes needed to be bartered or stolen, and he could not have left it to rust.

So two years passed, and Odds mother married Fat Elfred, who was amiable enough when he had not been drinking, but he already had four sons and three daughters from a previous marriage (his wife had been struck by lightning), and he had no time for a crippled stepson, so Odd spent more and more time out in the great woods.

Odd loved the spring, when the waterfalls began to course down the valleys and the woodland was covered with flowers. He liked summer, when the first berries began to ripen, and autumn, when there were nuts and small apples. Odd did not care for the winter, when the villagers spent as much time as they could in the villages great hall, eating root vegetables and salted meat. In winter the men would fight and fart and sing and sleep and wake and fight again, and the women would shake their heads and sew and knit and mend.

By March, the worst of the winter would be over. The snow would thaw, the rivers begin to run and the world would wake into itself again.

Not that year.

Winter hung in there, like an invalid refusing to die. Day after grey day the ice stayed hard; the world remained unfriendly and cold.

In the village, people got on one anothers nerves. Theyd been staring at each other across the great hall for four months now. It was time for the men to make the longship seaworthy, time for the women to start clearing the ground for planting. The games became nasty. The jokes became mean. Fights were to hurt.

Which is why, one morning at the end of Marchsome hours before the sun was up, when the frost was hard and the ground still like iron, while Fat Elfred and his children and Odds mother were still asleepOdd put on his thickest, warmest clothes, stole a side of smoke-blackened salmon from where it hung in the rafters of Fat Elfreds house and a firepot with a handful of glowing embers from the fire; and he took his fathers second-best axe, which he tied by a leather thong to his belt, and limped out into the woods.

The snow was deep and treacherous, with a thick, shiny crust of ice. It would have been hard walking for a man with two good legs, but for a boy with one good leg, one very bad leg and a wooden crutch, every hill was a mountain.

Odd crossed a frozen lake, which should have melted weeks before, and went deep into the woods. The days seemed almost as short as they had been in midwinter, and although it was only midafternoon it was dark as night by the time he reached his fathers old woodcutting hut.

The door was blocked by snow, and Odd had to take a wooden spade and dig it out before he could enter. He fed the firepot with kindling, and tended it until he felt safe transferring the fire into the fireplace, where the old logs were dry.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Odd and the Frost Giants»

Look at similar books to Odd and the Frost Giants. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Odd and the Frost Giants and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.