ALSO BY LAURENCE LEAMER

Madness Under the Royal Palms: Love and Death Behind the Gates of Palm Beach

Fantastic: The Life of Arnold Schwarzenegger

Sons of Camelot: The Fate of an American Dynasty

The Kennedy Men, 19021963: The Laws of the Father

Three Chords and the Truth: Hope and Heartbreak and the Changing Fortunes in Nashville

The Kennedy Women: The Saga of an American Family

King of the Night: The Life of Johnny Carson

As Time Goes By: The Life of Ingrid Bergman

Make-Believe: The Story of Nancy and Ronald Reagan

Ascent: The Spiritual and Physical Quest of Willi Unsoeld

Assignment: A Novel

Playing for Keeps: In Washington

The Paper Revolutionaries: The Rise of the Underground Press

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In Memory of David B. Fawcett Jr.,

19272012

CONTENTS

Prologue

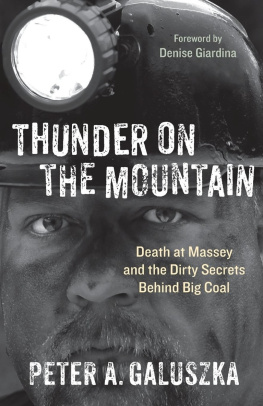

When I was a young man, I worked in a coal mine in southern West Virginia. It was 1971, and I had read Night Comes to the Cumberlands, Harry Caudills classic account of the deprived, exploited people of the Appalachian highlands in eastern Kentucky. I realized that amid the poverty and pain, there was something gritty and real in those lives that was absent from my own. So I gave up my apartment on the West Side of Manhattan and drove down to West Virginia, hoping to write about the region and its people.

In the coal fields, it was a time of turmoil. In 1969, Joseph Jock Yablonski, the defeated reform candidate for the presidency of the United Mine Workers (UMW), had been shot to death in his bed along with his wife, Margaret, as had their twenty-five-year-old daughter, Charlotte. The fear and paranoia in the industry did not lessen until four years later, when Anthony Tony Boyle, the president of the United Mine Workers, was convicted for having ordered Yablonskis murder.

When I arrived in southern West Virginia, the reformist Miners for Democracy was campaigning to take over the corrupt union. The coal companies, meanwhile, were nervous about what they considered outside agitators trying to stir up the miners. The only contact I had was a friend of a friend who ran a furniture store in Beckley, population 16,000the largest town in south-central West Virginia. He said that if I truly wanted to learn about this world, the best way to do it was to become a coal miner.

The UMW and the Westmoreland Coal Company agreed that I could work in a mine as long as I didnt tell anyone else I was a journalist and wrote only about the job and its particulars, not union politics. And so the next day I went to work on the hoot owl shift, from midnight to 8:00 A.M. , in the mine outside Beckley known as Eccles No. 6.

That first night, I showed up in the bathhouse, where the men changed before their shift and where they showered off the coal dust afterward. I arrived just as the second shift was leaving the mine. In my new work pants, long-sleeved green shirt, and unblemished black helmet, I looked like the greenhorn I was. Taking the elevator 150 feet down the shaft with the other men on the shift, I was nervous. In a seam 300 feet beneath the one in which I would be working, 186 miners had died in a 1914 blast, the second-largest disaster in the states mine history. A decade later, nineteen men had died in another explosion.

There hadnt been another accident of that magnitude since, but every time a man went down in the mines he put a tin tab with his name on it on a board in the bathhouse; he took it off when he came back up after finishing his shift. If he was trapped or dead, the octagonal medal would tell the tale.

During a lifetime in the mines, a worker averaged three or four accidents serious enough to require time off. And when miners retired, they often wheezed with black lung diseasea debilitating affliction that came from inhaling too much coal dust for too longor had other life-shortening ailments.

Despite the risks, the mines were the one place a man without much of an education could make a decent living. At that time, there was one other way the men could earn good moneyby leaving the mountain land they loved to work on the auto assembly line in Detroit.

That was why the miners believed me when I told them that I was a garage mechanic from upstate New York and had come down because I needed work. It made sense to them that a man might have to leave everything he cared about to go to a strange place to make a living. Almost from my first night, the miners accepted me as one of them. That was important, for if the men didnt like you, you probably wouldnt last.

These days, before a man goes down in the mine for the first time, he must sit through a week of safety classes. Back in the 1970s, there was no such preparation. A trainee depended on his fellow miners to show him ways to protect himself: how to avoid the overhanging open wires, which would electrocute him, and how to tie his bootlaces so they would not catch in the conveyer belt and drag him down to be mangled or killed.

For the first few nights, I worked resupplying the mine for the daytime shifts, and then I became a member of an eight-man mining crew. One miner in our group worked the continuous mining machine, which clawed out the coal with its whirling, sawlike blades. Two shuttle-car drivers scooped up about five tons of the newly mined coal at a time and carried it back to the conveyer belt. The shuttle-car drivers were expert at their job, but they always spilled some coal on the ground next to the belt. I stood at the belt and shoveled that coal onto it. If I didnt keep up, the belt might go down or the shuttle cars wouldnt be able to deliver their coal properly. I had to be constantly alert for the shuttle cars as they groaned through the tunnel like mammoth centipedes, their headlights breaking through the blackness. On one of my first nights, I broke my finger in two places.

During the lunch break and when the equipment was down, we had plenty of time to talk. I soon realized that most of the miners, unless theyd served in the military, had been no more than fifty miles from Beckley their entire lives and could not really talk about the world much beyond the mine and these mountains. In some ways, these men were almost as isolated from the rest of America as their ancestors had been a hundred years ago, when they had lived off the land in these mountain hollows. Some of them had worked thirty years in the mines and could remember the days before the mechanization of the industry, when they had mined with picks and shovels.

At the end of the shift, heading out, we squeezed past car after car of the coal we had just mined. On a good night, there might be eighty cars or more. Many people feel sorry for coal miners, but the men I worked with were proud of their jobs. And for good reason: they knew they had done something of measurable value, and each morning they saw precisely what they had accomplished. The miners did not talk about what those coal cars symbolized, but without coal there would have been no Industrial Revolution. We now know how coal-powered electric plants pollute the air, and we are slowly moving away from their use. But even at the end of the industrial age, without coal the lights of America would grow dim and there would be no coke to make the steel that constructs the buildings in our cities and towns.