Contents

Guide

Desperate

An Epic Battle For Clean Water And Justice

In Appalachia

Kris Maher

For the people of the Forgotten Communities

It is a region of black riches concealed under green velvet.

Oliver F. Holden, mining engineer, September 1921

PART I BLACK WATER FEBRUARY 2004MAY 2005

CHAPTER 1

K evin Thompson had been hunting for evidence all afternoon. A lone figure trekking through a rolling three-thousand-acre property in Mingo County, West Virginia, the forty-year-old attorney had climbed over barbed-wire fences and hiked up and down ridges on behalf of a client who was suing Arch Coal, one of the nations biggest coal companies, for contaminating his land. With his tan floppy hat, a backpack stuffed with topographic maps, and binoculars strung around his neck, Thompson looked more like a reality-TV explorer than a lawyer. For safety reasons, he was wearing steel-toe boots and carrying a hard hat. He knew he probably should have told the coal company that he would be out on his clients property that day but he wanted to cover the ground without interference. A quarter of a mile away, beyond a rise, bulldozers and giant rock trucks were moving dirt on a flattened ridge, and coal that had been buried for millions of years lay black as velvet in the sun.

As he hiked up a valley fill, a steep slope of churned-up dirt, Thompson scanned the ground for signs that the workers hired by an Arch subsidiary had illegally dumped fuel and machinery there. On previous visits, Thompson had found tainted water seeping out of the ground. As an environmental engineer had recently told him, black water meant diesel was oozing to the surface, and red water came from rusting equipment. While hiking higher, he listened for the beeping of trucks on the other side of the ridge. He knew that as long as the miners were moving coal around, he didnt have to worry about rocks raining down on him from another blast on the mountain.

Thompsons client James Simpkins was a prominent local businessman who sold lumber and mining equipment. He supported mining on his remote spread and had even mined large tracts of it himself, slopes that were now covered with thick grasses where his prized Angus cattle grazed. But he believed the coal company had been negligent and contaminated his property with fuel and machinery. Hed hired Thompson a few months earlier after watching him win a sizable settlement against Arch for an adjacent landowner. Simpkins told people he admired the young mans hustle. He liked Thompson, he said, even if he was a lawyer.

Thompson had a full head of light auburn hair, a resonant baritone voice, and an occasional stutter when too many thoughts crowded his brain. He also had a wife and daughter at home in New Orleans, where he rowed crew on the bayous to keep in shape. In the 1990s, he had built a successful litigation consulting business there and narrowly missed making a fortune when a chance to sell it fell through. But then an undeniable urge had led him to stake a claim as an environmental lawyer in southern West Virginia. After years of working as a consultant, he found he was drawn to the detective work of litigation as much as he was to arguing before a judge in a courtroom. And the coalfields were only a two-hour drive south from his hometown of Point Pleasant, close enough that he could stay there and keep an eye on his aging mother.

It was February 2004, and after working for a year and a half on two contamination lawsuits against Arch, Thompson was still getting his footing in the coalfields. He hadnt found any new evidence on the valley fill that day, but before climbing down he stopped to take in the view. The series of ridges around Simpkinss property was called Mystery Mountain. And that seemed appropriate enoughthis part of the state was still largely a mystery to Thompson. Now the gray and ocher ridges of the Appalachian Plateau, still bare from winter, stretched into the blue distance like swells in a choppy sea. Its the most amazing view youve ever seen, he often told people. Its crazy up there.

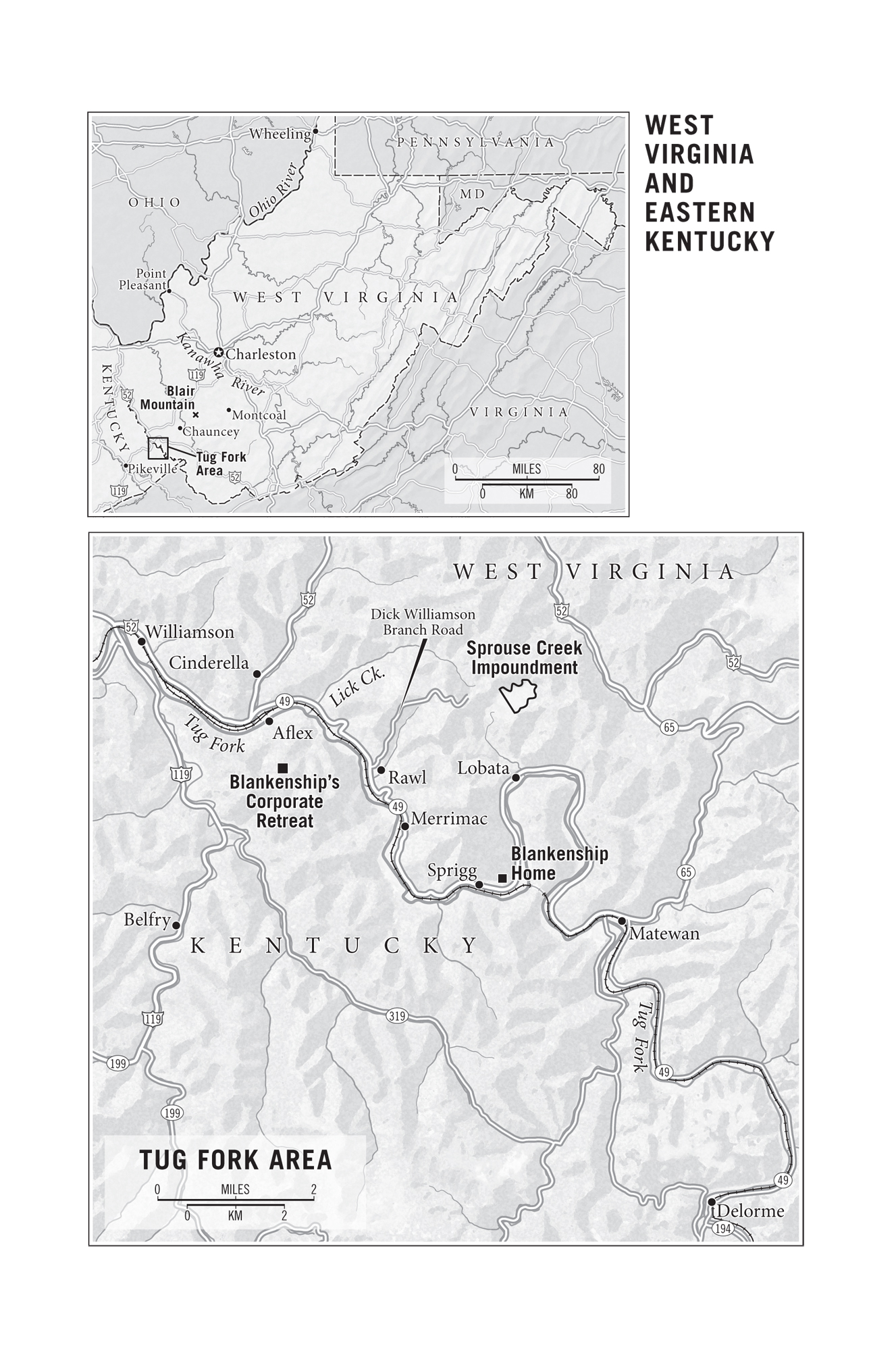

On his way to his car, Thompson remembered he had an appointment with three potential clients: a preacher named Larry Brown, his brother Ernie Brown, and another man named B.I. Sammons. He had a scrap of paper with directions to a church nearly an hour away. He threw his gear into his Ford Explorer and realized he had just enough time to make it. He thought about stopping to clean uphis right hand, which hed snagged on a fence, had dried blood on it and his pants were caked with dirtbut he decided showing up on time was more important. All he knew about the three men who wanted to meet him were their names and that they lived in a place called Rawl. It didnt strike Thompson as a complicated matter. B.I. had simply said that their wells had gone bad. As he drove down Route 49 beside the Tug Fork, a winding tributary of the Big Sandy River on West Virginias rugged border with Kentucky, Thompson figured a coal company must somehow be involved.

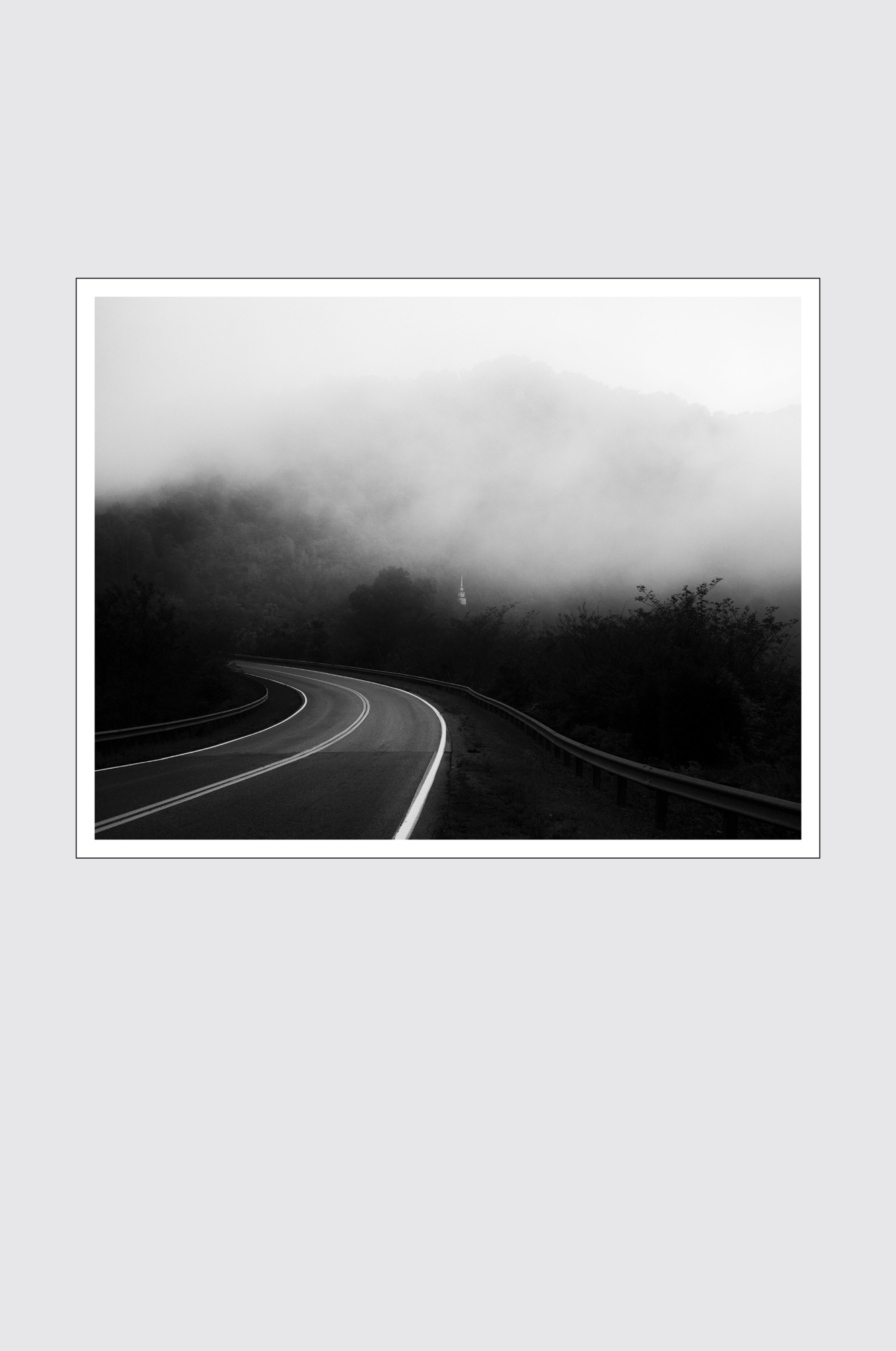

When Thompson turned onto Dick Williamson Branch Road, he found an old coal-mining community set in a hollow between low hills. The square houses with porches and newer double-wide homes were crowded close to a single lane of pavement, their tiny yards hemmed in by chain-link fences. Thompson slowed as a few barking dogs trotted into the road. At the top of the hollow, which was already in shadow, he came to a plain white church with a steeple. He noticed an ancient coal company house next to it that was weathered and gray. Then Thompson saw bright plastic toys in the yard and realized a family was living there.

Inside the Rawl Church of God in Jesus Name, more than fifty people filled the pews, and at first Thompson thought he had interrupted an evening service. The last of the sunlight was hitting imitation stained-glass windows: a white dove and a ray of yellow light against a scattering of abstract blue and green shapes. A few heads turned when Thompson entered, and then a tall man with narrow shoulders and large, silver-framed glasses approached him and asked if he was a lawyer.

Im not dressed like one, but I am, Thompson said. The man introduced himself as Larry Brown, pastor of the church, and Thompson realized that all the people in the pews had been waiting for him. Larry Brown brought Thompson over to his brother Ernie, who had dark-brown hair and looked about twenty pounds heavier and ten years younger. Then Larry introduced Billy Sammons Jr., who went by B.I. and wore a plain white trucker hat over his white hair. Ernie Brown and B.I. seemed eager to talk, but Larry hushed them. This is the fella we want to hear from, he said.

Brown walked Thompson up the blue-carpeted aisle to an altar that looked more like a stage set for a high school band concert, with microphones, acoustic guitars, and a drum kit. A seven-foot-tall white cross, with a wooden crucifix at its center, hung on the wall. Just tell the people a little about yourself, Larry Brown said.

Thompson looked out on the room full of people. After spending the day wandering around with only his own thoughts, it took him a few seconds to adjust to the crowd. But once he started talking, the words came easily. He introduced himself and said he focused on cases involving contamination from mines and other sites, and then he cut the tension in the room by apologizing for his appearance.