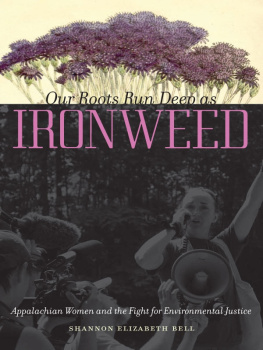

OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP AS IRONWEED

O UR R OOTS R UN D EEP AS I RONWEED

Appalachian Women and the Fight for Environmental Justice

SHANNON ELIZABETH BELL

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2013 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bell, Shannon Elizabeth.

Our roots run deep as ironweed : Appalachian women and the fight for environmental justice / Shannon Elizabeth Bell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03795-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07946-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09521-4 (ebook)

1. WomenAppalachian RegionPolitical activity.

2. Women and the environmentAppalachian Region.

3. Human beingsEffect of environment onAppalachian Region.

4. EnvironmentalismAppalachian Region.

I. Title.

HQ1236.B365 2013

305.40974dc23 2013017243

For Cedar.

Now I truly understand.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I cannot begin to express how deeply grateful I am to the twelve strong, brave, and determined women whose stories fill this book. Donetta Blankenship, Teri Blanton, Donna Branham, Pauline Canterberry, Maria Gunnoe, Debbie Jarrell, Maria Lambert, Joan Linville, Mary Miller, Patty Sebok, and Lorelei Scarboro, you are amazing individuals. Judy Bonds, words do not adequately convey how much you are missed and what an inspiration you have been, and continue to be, in my life and in the lives of so many others. I have learned so much from all of you and am eternally thankful that I have had the chance to meet you, hear your stories, and share your stories with others.

Thank you also to Lisa Henderson Snodgrass, Andy Mahler, Vernon Haltom, Maria Gunnoe, and Bill Price for allowing me to include the beautiful tributes you spoke and sang at Judy Bondss memorial service in January 2011.

My dear friends Vivian Stockman and Tricia Feeney with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition deserve special recognition and thanks for connecting me with many of the women in this book. Thanks also to Sarah Haltom, Vernon Haltom, and Matt Noerpel from Coal River Mountain Watch, who also helped me to make connections in the community. I would also like to acknowledge Melissa Ellsworth and Manali Sibthorpe, who were wonderful companions during a number of my interviews.

The Center for the Study of Women in Society (CSWS) at the University of Oregon believed in this project when it was just an idea in a new graduate students mind. Many thanks to CSWS for providing me with a Graduate Student Research Support grant during the summer of 2007 to conduct the bulk of the interviews for this research. Thank you also to the following agencies and grant programs that funded the Photovoice component of this research: the University of Oregon Department of Sociology Wasby-Johnson Award; the American Sociological Associations Sydney S. Spivack Program in Applied Social Research and Social Policy Community Action Research Initiative Grant, the Greater Kanawha Valley Foundation, the Appalachian Regional Commission, CSWS, and the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition.

I am indebted to my colleagues and mentors who read and commented on drafts and chapters of this manuscript during its various stages: Yvonne Braun, Joan Acker, Sherry Cable, Betsy Taylor, Sandra Ballard, Richard York, Dwight Billings, and Sandra Morgen. Thank you also to Gender & Society for allowing me to reproduce parts of Yvonne Brauns and my 2010 article, Coal, Identity, and the Gendering of Environmental Justice Activism in Central Appalachia in this book.

I am so grateful to Laurie Matheson at University of Illinois Press for her enthusiasm for this project and for believing in the importance of this book from the beginning.

Thank you also to my parents Susan and Tom Bell, who have unconditionally supported me and who have been my constant cheerleaders, no matter how far from home my projects and dreams have taken me.

Finally, I want to express my deep gratitude and appreciation for my wonderful partner Sean Bemis and the endless ways he continues to support me and our family. Thank you for your love and for always knowing how to make me smile.

Note to Readers

Throughout the text I use the term women activists rather than female activists to describe the individuals in the book. While I recognize that it is more grammatically sound to use female (an adjective) than it is to use women (a noun) to modify activists, doing so would not be analytically correct. In this book I am examining the ways in which these activists social location in the gender hierarchy affects their activismnot how their biological sex affects it.

List of Figures

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

| : |

INTRODUCTION

Its not just what I choose to do, its also, I think, what I have to do. Ive always been a very fierce protector of my kids, and Im still doing that. Im still protecting what I have left. Not only [my house and land], but the mountain behind it and the environment and the wildlife and the vegetation. The majority of the Appalachian women that I know were born fighting and protecting.

LORELEI SCARBORO, 2008

People say that ironweed is the symbol for Appalachian women. You know that tall purple flower thats all over the mountains at the end of summer? Have you ever tried to pull it out of the ground? Its called ironweed because its roots wont budge. Thats like Appalachian womentheir roots are deep and strong in these mountains, and they will fight to stay put.

JUDY BONDS, 2006

Black coal dust rains down on a town, destroying property values as well as residents lungs. A housewith a family insideis nearly washed away by a flash flood caused by the presence of a mountaintop-removal mine. A breach in an underground coal waste injection site pollutes the well water of an entire community, and years pass before the toxic contamination is discovered. These

The tremendous environmental burdens the people of Central Appalachia have been forced to bear is part of a global pattern of inequality. Not all people share the weight of the worlds environmental hazards and pollutants equally; those with the least political and economic powerpeople of color, low-income communities, and residents of the global Southbear a disproportionate share of the waste, pollution, and environmental destruction created by society (Bullard 1990; Bullard et al. 2007; Masterson-Allen and Brown 1990; apek 1993; Pellow 2004; Pellow 2007; Faber 2008; Faber 2009). Coal is cheap, but only because the costs of energy production are externalized onto the natural environment and society in the form of pollution, destruction of the land, and limited economic opportunities.

a struggle that has largely been initiated, led, and sustained by working-class women. This book is about some of those powerful, dedicated, tenacious individuals.

Preserving Womens Place in the History of the Central Appalachian Environmental Justice Movement

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.