To all women, past, present, and future, who have fought hard for our rights and our opportunities. May we always persist.

Published in 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lusted, Marcia Amidon, author.

Title: The fight for womens rights / Marcia Amidon Lusted. Description: First edition. | New York, NY: Rosen Publishing, 2020. | Series: Activism in action: a history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018017504| ISBN 9781508185536 (library bound) | ISBN 9781508185529 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Womens rightsHistoryJuvenile literature. | FeminismHistoryJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HQ1236 .L87 2019 | DDC 305.4209 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018017504

Manufactured in the United States of America

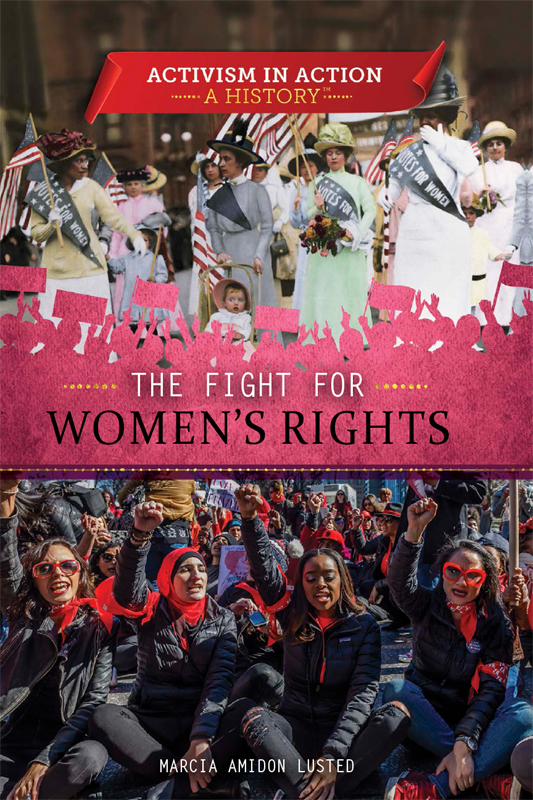

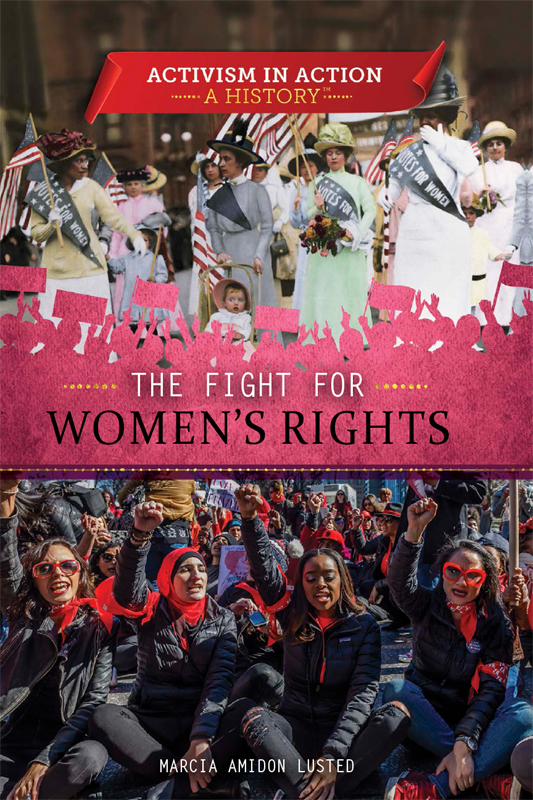

On the cover: Activists have long-advocated for womens rights by participating in public demonstrations, including the 1912 Suffrage parade in New York City (top) and the 2017 International Womens Strike in fifty countries (bottom).

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

F or as long as society has existed, there has been a conflict about the role of men and women, and whether or not women and men should have equal footing. While history tells us that women have seemingly been resigned or even content with their prescribed roles as wives, mothers, and housekeepers, it is also a fact that, historically, womens voices, experiences, and opinions have rarely been written down or remembered. Womens history has some powerful role models, like Queen Elizabeth, who ruled England in the late 1500s, half-mythical figures, like Queen Boudica, who led British Celtic tribes against the Romans in 60 CE, and Cleopatra, who ruled the Egyptians until 30 CE. But there have not been enough actual voices for womens rights from real women who struggled and suffered and worked and demanded equality with men, because the work they did and the words they spoke were not valued.

Women did not make much progress in gaining their rights until they began to be heard. In 1792, English writer Mary Wollstonecraft wrote a pamphlet called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, arguing that it wasnt that women were inferior to men, but only that they werent given enough education to compete with men. She suggested that women should be given equal access to education and schooling and that a nations well-being depended on the essential contributions of women. Slowly, more women broke down barriers to make their voices heard, to become educated, and to gain ground in seeking womens rights.

Elizabeth I, who ruled England and Ireland from 1558 to 1603, is considered by many to be the greatest monarch in British history.

The history of womens rights in the United States and all around the world is one of women standing up and telling their stories, and then standing up to the forces that would keep them from being equal citizens and partners. Womens stories are essential to the struggle for equal rights. As author Rebecca Solnit wrote in the Guardian newspaper in 2017:

Being unable to tell your story is a living death, and sometimes a literal one. If no one listens when you say your ex-husband is trying to kill you, if no one believes you when you say you are in pain, if no one hears you when you say help, if you dont dare say help, if you have been trained not to bother people by saying help. If you are considered to be out of line when you speak up in a meeting, are not admitted into an institution of power, are subject to irrelevant criticism whose subtext is that women should not be here or heard. Stories save your life. And stories are your life.

The fight for womens rights is not over, and perhaps never will be. But listening to the voices of women who have brought us to this point, and tracing the path that the feminist movement has followed will help to continue the forward motion that will move todays girls along the path to becoming women with equal rights and an equal place in their societies, tomorrow.

CHAPTER ONE

IN THE BEGINNING

F rom the vantage point of the twenty-first century, it can be difficult to imagine a time when women had virtually no rights,

and often their fathers or husbands made their decisions for them. However, women living during the early years of the United States, in Colonial America, were strictly confined to rigid gender roles, had very little freedom of choice, and no legal rights. Much of this was due to strong religious values, which taught that women were to be subservient to men. Their role was to maintain the household and raise children. The Christian Bible taught that women were inferior to their male counterparts, and more given to sin, so they were subservient first to their fathers and then to their husbands. Under Colonial laws, single women could not sue or be sued or enter into contracts. Women might be taught to read, enabling them to read the Bible, but otherwise many women were not educated.

This young Puritan woman was taught the skills to be a good housewife and to be subservient to her husband.

BEING POWERLESS

A married woman was legally powerless. Her husband controlled all of her property, even that which was hers before she got married, and he had complete legal control of their children. Divorce was not allowed. Women could not vote. They could not speak during church services or town meetings and had no voice in selecting ministers or in town affairs. The Puritan leader William Bradford wrote, according to Gail Collins Americas Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines, Touching our government, you are mistaken if you think we admit women for they are excluded, as both reason and nature teacheth they should be.

Women might contribute to the family finances by raising chickens for eggs and making butter, or by creating textiles. But these would be sold by her husband and, most often, the money remained under his control. Of course, there were exceptions, occasionally a woman was forced by her husbands absence to take over some control of family businesses. She could do the work of a printer, storekeeper, or farmer, but she couldnt actually have that title. The few occupations that were open to women were running a tavern or being innkeepers since these jobs were closely related to running a house. Midwives were women, but some Colonial women worked as doctors as well. A woman known as Mistress Allyn served as an army surgeon during King Philips War and was paid twenty pounds in British money. Of course, her male counterparts made three times as much money to do the same job.

SHE VOTED

One Colonial woman did manage to vote. Lydia Chapin Taft of Uxbridge, Massachusetts, went to the local town meeting in 1756. Because her husband had recently died, just before an important town vote concerning the French and Indian War, she cast a vote in his place. Taft would vote in a total of three town meetings, in 1756, 1758, and 1765. From 1775 to 1807, the constitution of the state of New Jersey permitted anyone with property valued at fifty pounds or more to vote, including single women. Taft was allowed to vote as a widow, but married women were not included because their property was considered to be their husbands.

Next page