To feminist readers of all ages

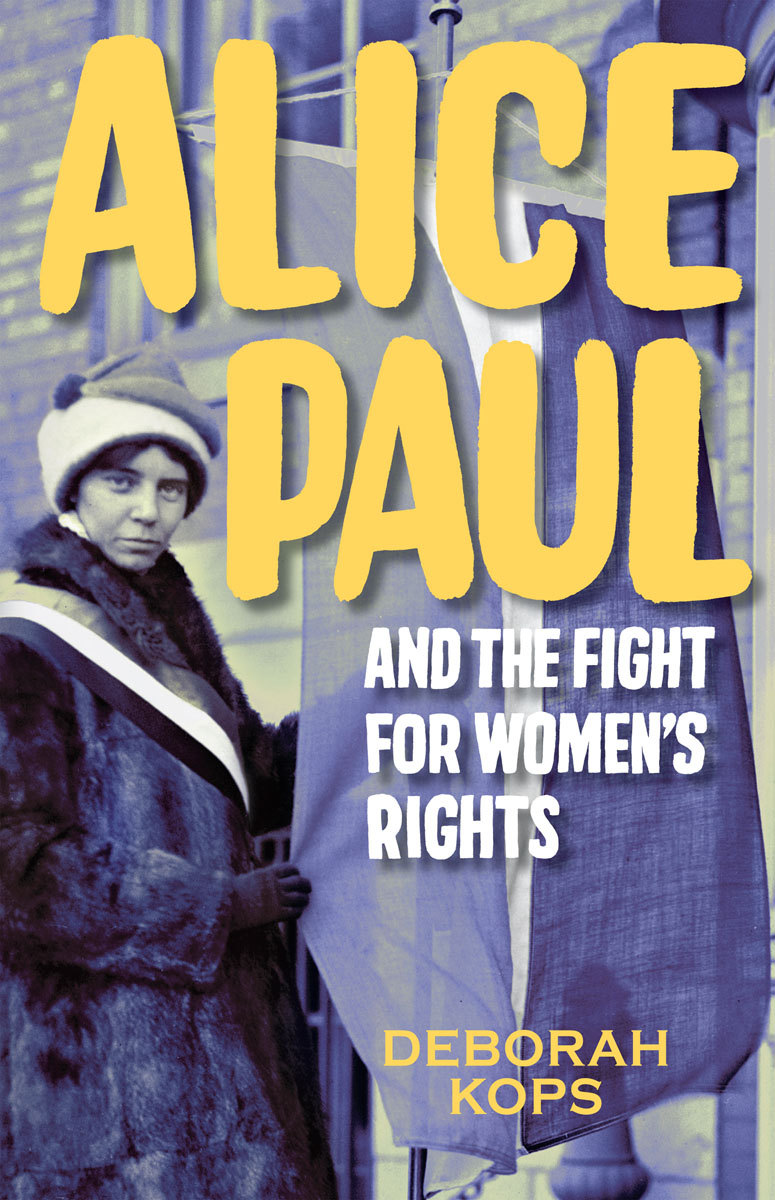

Text copyright 2017 by Deborah Kops

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, please contact .

Calkins Creek

An Imprint of Highlights

815 Church Street

Honesdale, Pennsylvania 18431

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-62979-323-8 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-62979-795-3 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016951184

First e-book edition, 2017

H1.1

Designed by Barbara Grzeslo

Production by Sue Cole

Chapter numbers are handlettered, titles are set in ITC American Typewriter Light Text set in Sabon

I never saw a day when I stopped working for womens rights.

Alice Paul

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

On a fall day in 1917, Alice Paul and three other women, all in coats and proper ladies hats, marched across Lafayette Park to the West Gate of the White House. Paul carried a banner with President Woodrow Wilsons solemn words: THE TIME HAS COME TO CONQUER OR SUBMIT . FOR US THERE CAN BE BUT ONE CHOICE . WE HAVE MADE IT . The president was referring to the countrys determination to win the Great War, which American soldiers were fighting alongside their allies on the battlefields of Europe. But the crowd that soon gathered knew Paul had a different struggle in mind: American women were fighting for the right to vote. The four women stood silently at the gate, but not for long. They, and their audience, were expecting what happened next: A police sergeant called for a patrol wagon, which came rushing through the citys congested streets, ringing its gong. The four were arrested for obstructing traffic and escorted to the wagon. Give them a year, a heckler shouted as they took off. Pauls banner, hanging out of the back of the wagon, flapped in the breeze.

At the police court, the judge scowled at Alice Paul, who had been there only two weeks earlier for the same offense. This small young woman, as thin as a wisp of hay, a friend once said, had by then deployed thousands of her troops from the National Womans Party to picket the White House. You force me to take the most drastic means in my power to compel you to obey the law, the judge said. He sentenced the women to at least six months in jail. Paul, a repeat offender and the head of the Womans Partyor, as the police thought of her, the ringleadergot seven months.

Before she climbed into a patrol wagon again and headed for jail, Paul got in the last word. I am being imprisoned, she told reporters, not because I obstructed traffic, but because I pointed out to President Wilson the fact that he is obstructing the progress of democracy and justice at home, while Americans fight for it abroad.

Who was this woman who challenged the president of the United States at the gates of the White House again and again? Who was this suffragist who inspired so many women to hold up banners prodding the president to help them win the vote, knowing they might pay for their banners with a jail sentence? Who was this feminist who thought that winning the ballot would not be enough, that women needed equal rights, too?

1

QUAKER ROOTS

Alice Paul was born in Moorestown, New Jersey, on January 11, 1885. An observant visitor wandering around this town, about fifteen miles from Philadelphia, would realize instantly that it was unusual. Men and women tended to dress plainly. Few women stepped out of carriages in brightly colored stylish dresses; they tended to wear muted or dark tones.

Local speech was even more striking than local dress. Have thee planted thy peas? a man might ask his neighbor in the spring. Almost everyone in Moorestown was a Quaker, and they had been using thee and thy since the 1600s. Back then, colonial Americans addressed anyone they considered inferior as thee, and everyone else as ye. Since Quakers believed strongly in equality, they always used thee, no matter how important or wealthy a person was. Moorestown had its share of wealthy families, though, and Alice Pauls was one of them.

Alice grew up in a large white stucco house with her younger brothers, William and Parry, and her sister, Helen. They played tennis on their front lawn, sometimes landing the balls among the sheep grazing on the nearby pasture of the familys farm. Ducks were also raised on the farm, and one of Alices chores was to count their eggs for her mother. Her father, William, was a stern man who knew he could rely on his eldest child. If there was something difficult and unpleasant that needed doing, he would say to Mrs. Paul, I bank on Alice.

Alice (left) at age nine and a half; her sister, Helen, age five; and her brother William, age eight. The photo was taken in 1894.

When Alice wasnt whacking tennis balls or doing farm chores, she was reading. What she loved were novels, but the towns public library had none because they were frowned upon by the strictest Quakers. So she read the novels of the great English writer Charles Dickens; her parents owned a complete collection. I remember reading every single line of Dickens as a child over and over and over and over again, she said later.

Alice (right) exercises with a friend when she is about fifteen years old.

On Sundays, the family went to Quaker meeting at the simple brick building in the center of Moorestown. There was no church steeple or stained glass and no minister standing up front to lead prayers. Instead, the meeting was a long period of silence, punctuated by a few Friends (that is how Quakers refer to themselves) who felt moved to share a spiritual thought.

Young Alice learned to be comfortable with silence at those meetings. Without really thinking about it, she also absorbed the Quaker beliefs that women and men were equals and that women had the same right to vote that men enjoyed. She didnt realize that not everyone felt that way, because she was surrounded by Quakers. I never met anybody who wasnt a Quaker, and I never heard of anybody who wasnt a Quaker except the maids, she once said. Later, she would discover that Quakers were well represented among the leaders of the long struggle for woman suffrage, or womens right to vote, including Susan B. Anthony, one of the greatest.

Alice attended the Moorestown Friends School from the time she was a child. While her female classmates tended to arrive in carriages, independent Alice made the one-mile trip from home riding bareback on her horse. When she graduated at the age of sixteen, she was at the top of her class. It was very small, five students in all.

On September 18, 1901, Alice Paul boarded a train for Swarthmore College, in Pennsylvania, about thirty miles from Moorestown. No doubt she was excited to be leaving home, but she was not venturing outside the Quaker fold yet. Swarthmore College was a Quaker school. Alices grandfather was one of its founders, and her mother attended for three years before she married.

Swarthmore admitted an equal number of young men and women, and it kept a sharp eye on its female students. Alice saw men in her classes, at meals, and during the after-dinner social hour, when a male friend might ceremoniously escort her to the parlor. At other times, women were expected to stay on the east side of the main building on campus. The enforcer of these rules was the sixty-year-old dean of women, Elizabeth Powell Bond.

Next page