LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1978-1

2015 Bernadette Cahill. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

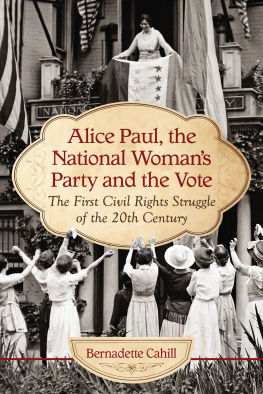

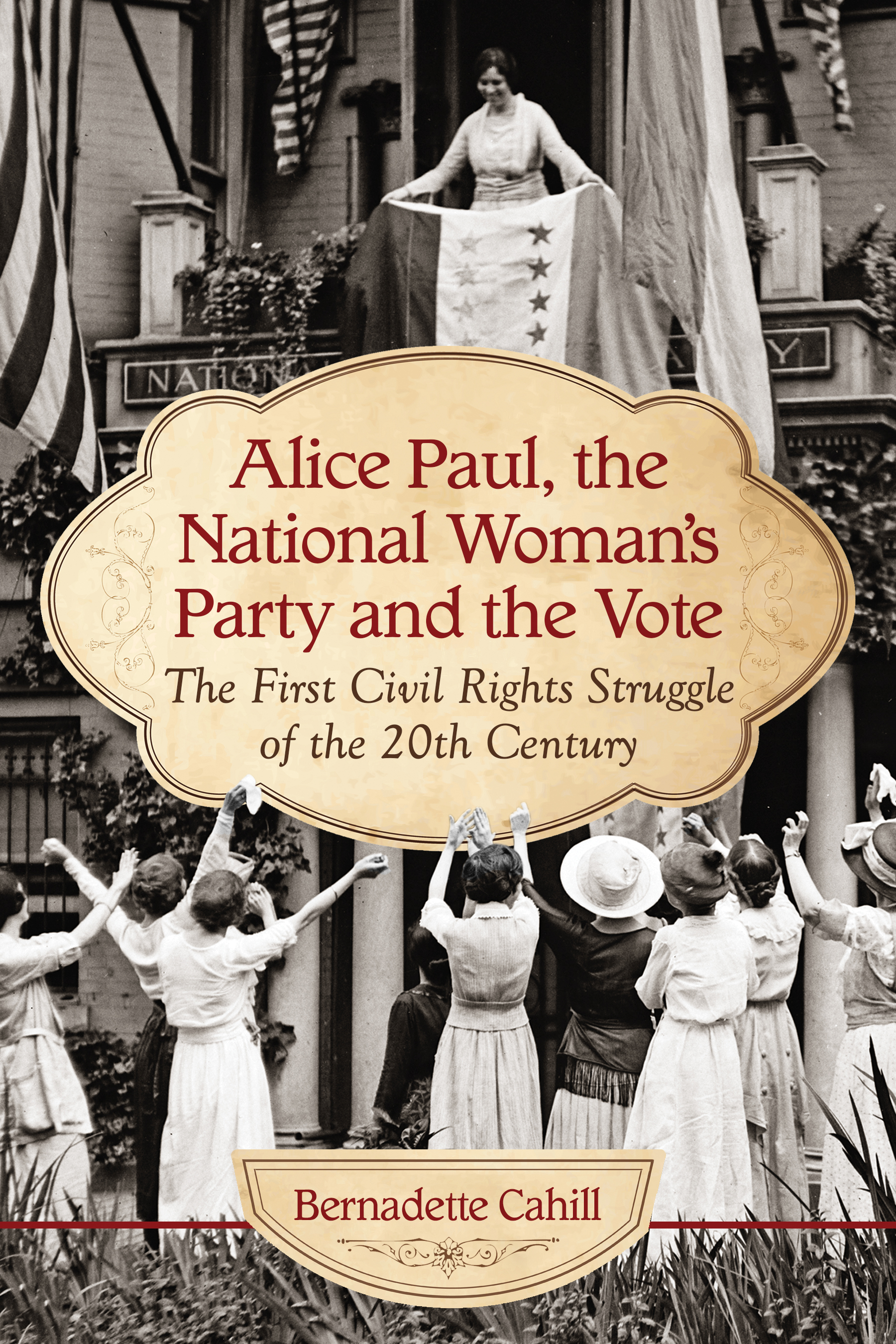

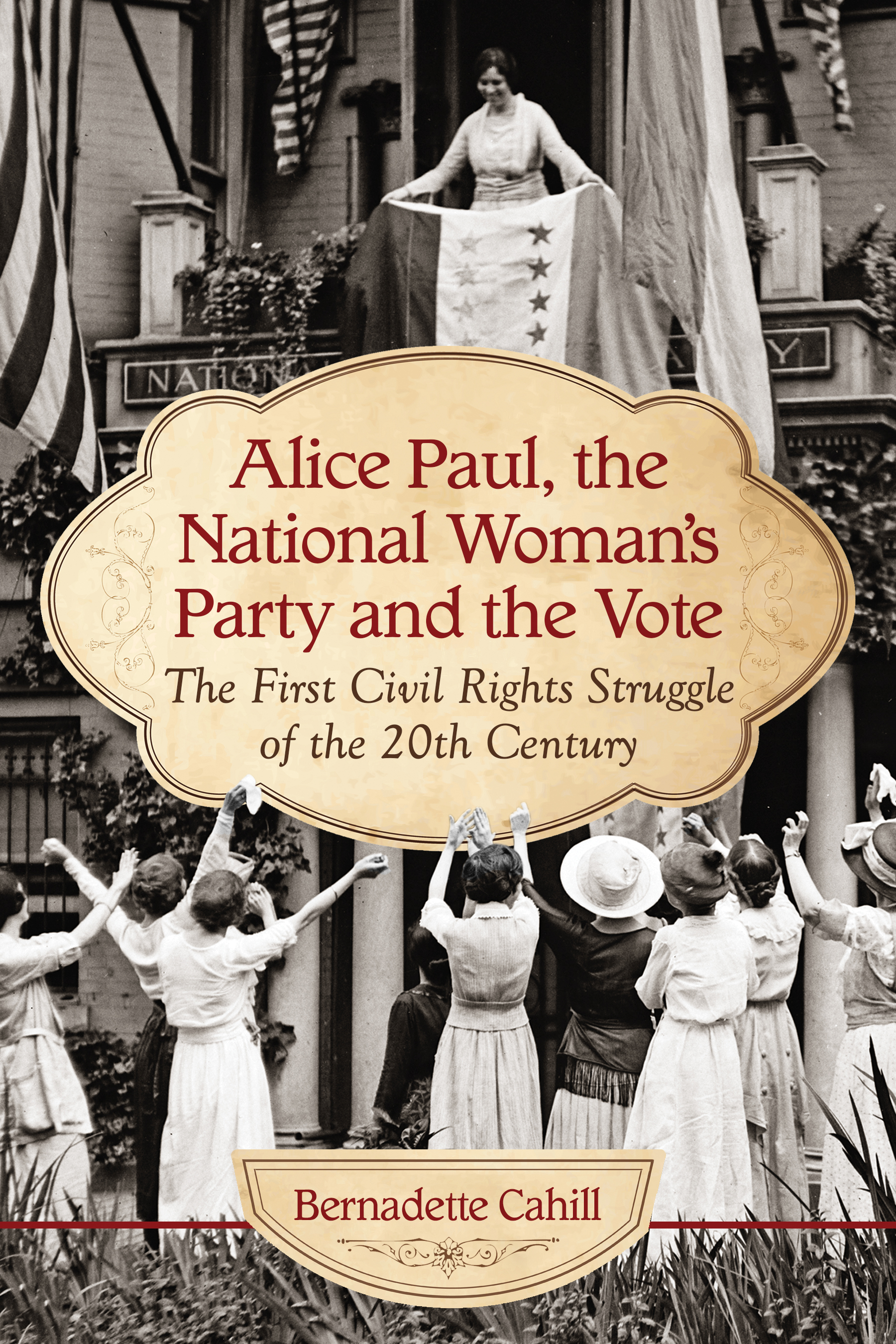

On the cover: Alice Paul, leader of the National Womans Party, unfurls the completed Ratification Flag in Washington, D.C., in August 1920 (Library of Congress)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To

Miss McCann

and to

Thomas Peter Cahill

Preface

The civil rights movement in the United States was about African Americans in the 1960s. That, at least, is how the term is defined in modern times. Whenever the civil rights movement is recalled, visions of marches, police dogs attacking protesters and Martin Luther King, Jr.s I have a dream speech reverberating around the Reflecting Pool in Washington, D.C., are what come to mind.

Yet, such a definition distorts the real history of civil rights. The fact is that campaigns for civil rights in the United States lasted much longer than a period in the middle of the twentieth century. Of equal importance, civil rights in the United States were never about only race: they also involved women and have included womens campaigns for equality under the law, which women have failed to win. They have included struggles for equality of education, of pay, for jobs and in countless other aspects of lifeall the same goals for which blacks have also struggled. Womens campaigns have included, specifically, the struggle for the right to vote. Yet these simple facts are today generally ignored. It was not always the case that women were excluded from the concept of civil rights; their exclusion from that concept seems to be a phenomenon of the past fifty years.

Another key fact in the history of these two struggles has also been lost. While they have had a direct impact on each other at key moments in their respective histories and the impact of the black movement on women has been recognized, the equally important influence of womens rights on blacks has largely been ignored. In particular, it is virtually unheard of that the black civil rights movement in the 1960s could not have achieved what it did when it did without the pivotal event of the victory of womens suffrage forty years earlier, specifically the campaign of Alice Paul and the National Womans Party. Yet the strategy of this group to bring the issue of votes by women right to the gates of the president in the teen years of the twentieth century established the model for succeeding sustained political activism and secured important precedents and rights that African Americans were able to utilize in their own struggle against racial inequality and discrimination.

The travails of the two movements may have been different in many details, but the movements had the same origin at the founding of the nation and they both have worked towards making the nation established on liberty and equality live up in practice to its principles. As such, the black civil rights movement and the woman civil rights movement are equal in import, as are their histories and influence on U.S. history. Yet today, the Civil Rights Movementcapitalizedis the name given to the sixties struggle for African American rights, while the still-incomplete struggle for the emancipation of women is referred to as womens rightsoften not capitalizedas if it is only a side issue. The former long ago won the goal of equality, in theory at least, in United States fundamental law. By contrast, the campaigns for womens civil rights a century after women won the vote have still not achieved that same basic goal. Further, the African American movement is constantly honored and recognized. Womens long struggle receives considerably less recognition in United States history and its significance is subordinated to that of black rights. The recognition that the womens struggle receives hardly accords with the percentage of women in the population. Further, there are distinct practical results for women and their history because of this second-class status in civil rights.

This book aims to rebalance this situation. It looks at these issues and examines the pivotal role of Alice Paul and the National Womans Party in helping to establish civil rights for all in the United States.

Introduction

This book is ultimately about place. It is about particular places in a key development in United States history and specifically about Alice Paul,

the National Womans Party (NWP) and the significance of each in that history. It is about neglected civil rights sitesthe places where Paul and the NWP struggled to win and guarantee the primary civil right of this nation, the right to vote, for 50 percent of the population.

This book grew out of two events in my own life: finding the Iron Jawed Angels movie and a visit to the nations capital in 2010. Iron Jawed Angels tells how a group of young women went to Washington, D.C., in late 1912 and until 1920 faced down the president of the United States in order to force a successful conclusion to the campaign for votes for women, which had been ongoing since 1848. A remarkable story of determination and unbounded courage, the victory of these women was so unquestionable that many people in the twenty-first century are unaware that the struggle took place.

My mothers work with Lilian Lenton in Britain for equal rights for women helped to spark my own lifelong interest in womens past. By spring 2008, in Boone, North Carolina, I was writing many articles for the local newspaper and magazine about womens history, particularly the Equal Rights Amendment. Iron Jawed Angels and further researches raised my knowledge level. Then in August 2010 a long-planned trip to Washington, D.C., turned out to coincide with a 90th anniversary demonstration at the White House for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. This triggered the idea of going to see for myself the places where the major scenes in Iron Jawed Angels had occurred. In particular, I wanted to know the actual location of the building with the balcony where Alice Paul had displayed the star-spangled NWP flag when the Nineteenth Amendment was promulgated. I assumed that not only would the building be marked clearly, but also that many other locations in Washington would be similarly marked. I also expected to find books easily on this specific subject.

I had expected a lot. During my few days in the area, I found that, apart from the White House and the Capitol, the Sewall-Belmont House Museum was the only building I could easily locate that was associated in some way with the NWPs campaign. Further afield, I did find the Occoquan museum in Lorton, about twenty miles to the south in Virginia, and Alice Pauls family home in Moorestown, New Jersey. Multiple searches on the Web while I was in Washington produced a brochure of womens history sites from the National Womans History Museum (NWHM). This raised my hopes, but, although it contained a useful summary of the suffrage struggle, it was empty of the kind of detail I wanted. My curiosity unsatisfied by this particular trip, I now immediately began a month of solid research on the Web while I also hunted for places and events through every book I could get my hands on about the final suffrage campaign in D.C. This period ended in another quick trip to Washington to locate and photograph the places I had found. My tour saddened me: so little of the city remained the way it was a century ago that pinning down specific locations was almost impossible.

Next page