All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

B ALLANTINE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Pat Humphries for permission to reprint an excerpt from Swimming to the Other Side composed by Pat Humphries, and 1992, published by Moving Forward Music. Reprinted by permission.

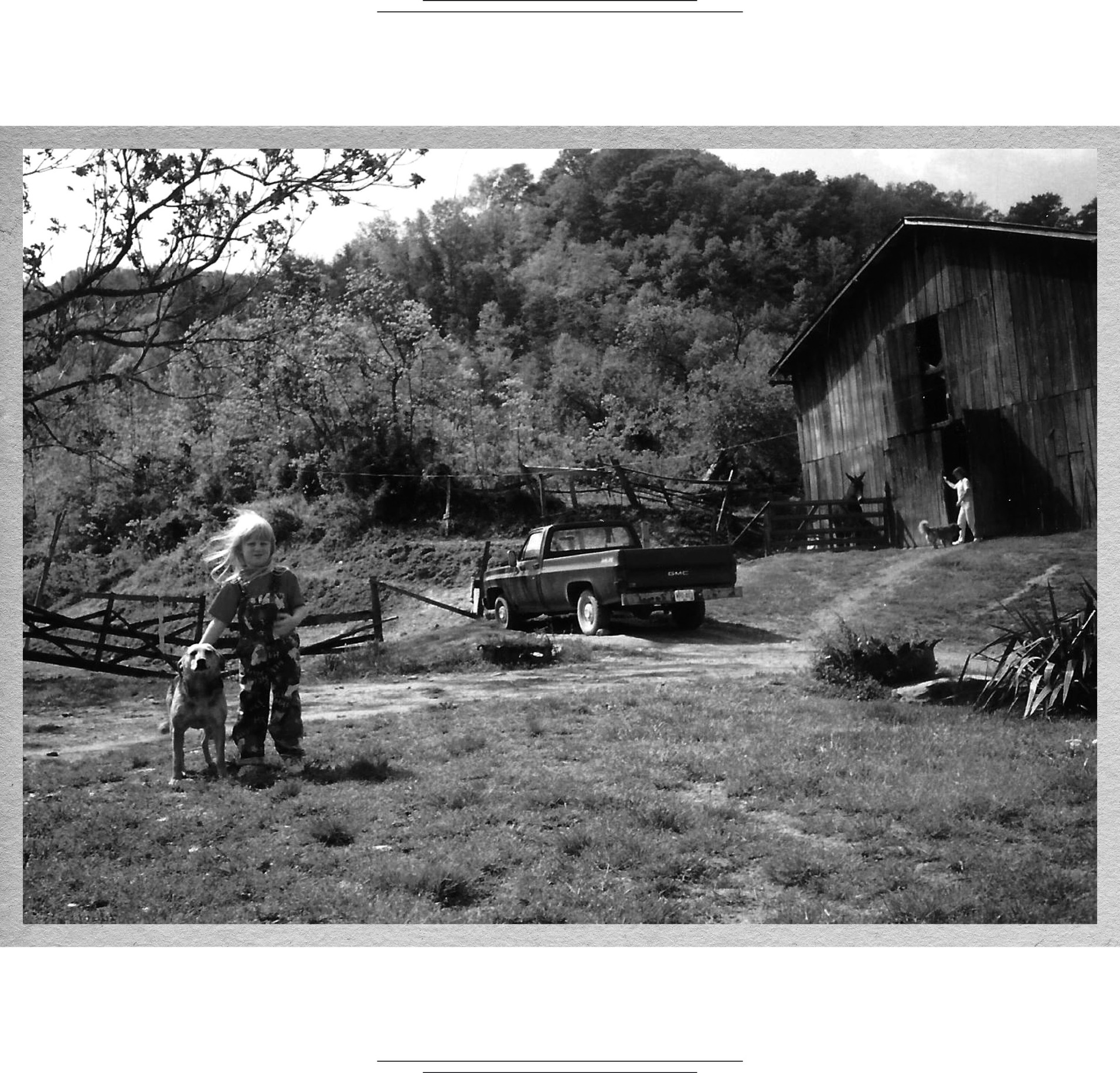

You dont go to Owsley County, Kentucky, without a reason. You cant take a wrong turn and accidentally end up there. Its miles to the nearest interstate, and theres no hotel in town. It doesnt cater to outsiders.

A half dozen times each year, I drive to Owsley County, where my mom grew up, and where, in many ways, I did too. The roads to this tiny Appalachian community wind tightly through the mountains, snaking around corners and plunging into valleys. Even after all my years of making the journey, I still feel a bit nauseous on some of the curves.

On this drive, Im talking to one of my legal clients on the phone. Yes, Ill meet you at the courthouse at eight A.M. Thursday, I yell, as though increasing my volume will make up for the patchy cell service. Yes, eight A.M. !

This client has called me repeatedly over the past few days, and this isnt the first time Ive confirmed the time of her hearing. We are going to court to get a protective order to keep her safe from her physically abusive husband. I can tell shes nervous.

I start to say something to comfort her, but Im interrupted by three short beeps letting me know that I haveonce againlost service. C ALL F AILED flashes across the screen, and I cant help but feel as though this call isnt the only thing failing in my legal practice these days. I decided to work as a legal services lawyer in rural Kentucky to make a differenceto represent women who couldnt afford an attorney. Everything is harder than Id anticipated. I sigh and switch on the radio.

Eventually the mountains give way to Booneville, the county seat and the only town for miles. From the top of the ridge I can see the town in its entirety, spanning just a few blocks, nestled in the holler below. I sigh again, this time with relief: It is always exactly how I remember it. There is comfort in that.

But once Im driving in Booneville, surrounded by its smallness, there is a moment where the comfort resembles confinement. The town itself feels stagnant, silent, unchanging. Occasionally a pickup truck roars around the block and breaks the quiet. The stores are worn around the edges, with faintly painted signs and pitched awnings that flap against the gray sky. There is no trace of new business or development. The megachain stores so familiar to most Americans are nowhere to be found. Two dollar stores and two gas stations are the only franchises in town.

The local high school proclaims itself the home of the Owsley County Owls. And that is how Owsley County is pronounced: Owl-sley County. The order of the letters in the word doesnt really matter. People give little thought to such formalities.

The 1970s-style courthouse occupies the center of the town square. I occasionally go there for my work as a lawyer. When I do, I chuckle as I pass the sign inside that reads N O T OBACCO U SE A LLOWED IN C OURTHOUSE. E XCEPT FOR THE O FFICE OF THE S HERIFF, C OUNTY T REASURER, AND C OUNTY C LERK. I used to think it was a joke, but a lawyer who works there assured me that its not. They banned smoking in the courthouse just a few years ago, and Im told some officials refused to go outside to have their cigarettes.

A plaque in front of the courthouse proudly states Boonevilles claim to fame: Daniel Boone once spent the night in the town square. Owsley County has another claim to fame: It is one of the poorest counties in America. According to the 2010 census, it has the lowest median household income$19,351anywhere in the United States outside of Puerto Rico. More than 45 percent of the population lives in poverty. Only 38 percent participates in the labor force, and more than 20 percent has a disability. Even those numbers dont accurately describe how deep the poverty runs here.

Its not always visible, the poverty. Some parts of town are stacked with rows of neat brick ranches and freshly painted homes. One bright yellow house flies an American flag and has a beautiful birdbath in the front yard. Another has a border of flowering trees and well-manicured bushes. These parts of Booneville could be any small town in America.

But in some places the poverty is all that you can see: the places scattered with houses and trailers falling in on themselves, the structures so tilted and crooked it looks like a stiff wind might knock them over. The gaps in some of the wooden houses are visible from the road, and Im told that at least a few of them still have dirt floors. At first glance, these places look abandoned. But a vehicle in the driveway is a marker that this sagging structure is someones home.

Its hard for me to know which part of Owsley County I should show the rest of the world. Presenting the broken, falling-in places helps people understand the extent of the poverty. And I do want them to know how deep it goes. Maybe if they understand it, they can help fix it. But I also dont want them to think that this poverty is all that exists in Appalachiato see Eastern Kentucky as hopeless, broken, dirty. Thats not what I see when I look at this place that I love.

I round the square and continue driving. Along the way, some of the lawns are scattered with what appears to be junk: old car parts, refrigerators, childrens toys. But I know that, for some people, the piles of seemingly useless stuff serve a purpose, and an entrepreneurial one at that. People here make a living however they can: selling old car parts, repairing refrigerators, organizing yard sales. They collect anything of possible value because they never know what will come in handy. If nothing else, they can sell the junk in a nearby town for fifty dollars a truckload. They are always thinking of ways to earn money, help a neighbor, provide for their family. There is drive, creativity, effort in unexpected places.

Some people look at this image of poverty with a sense of disgust: they see unkempt humans living in unkempt homes. Others view it with a sense of pity: those poor people, trapped in such awful circumstances. I try to look at it with a sense of respect: to remember how hard they are working to survive in the overlooked corner of the world they call home.