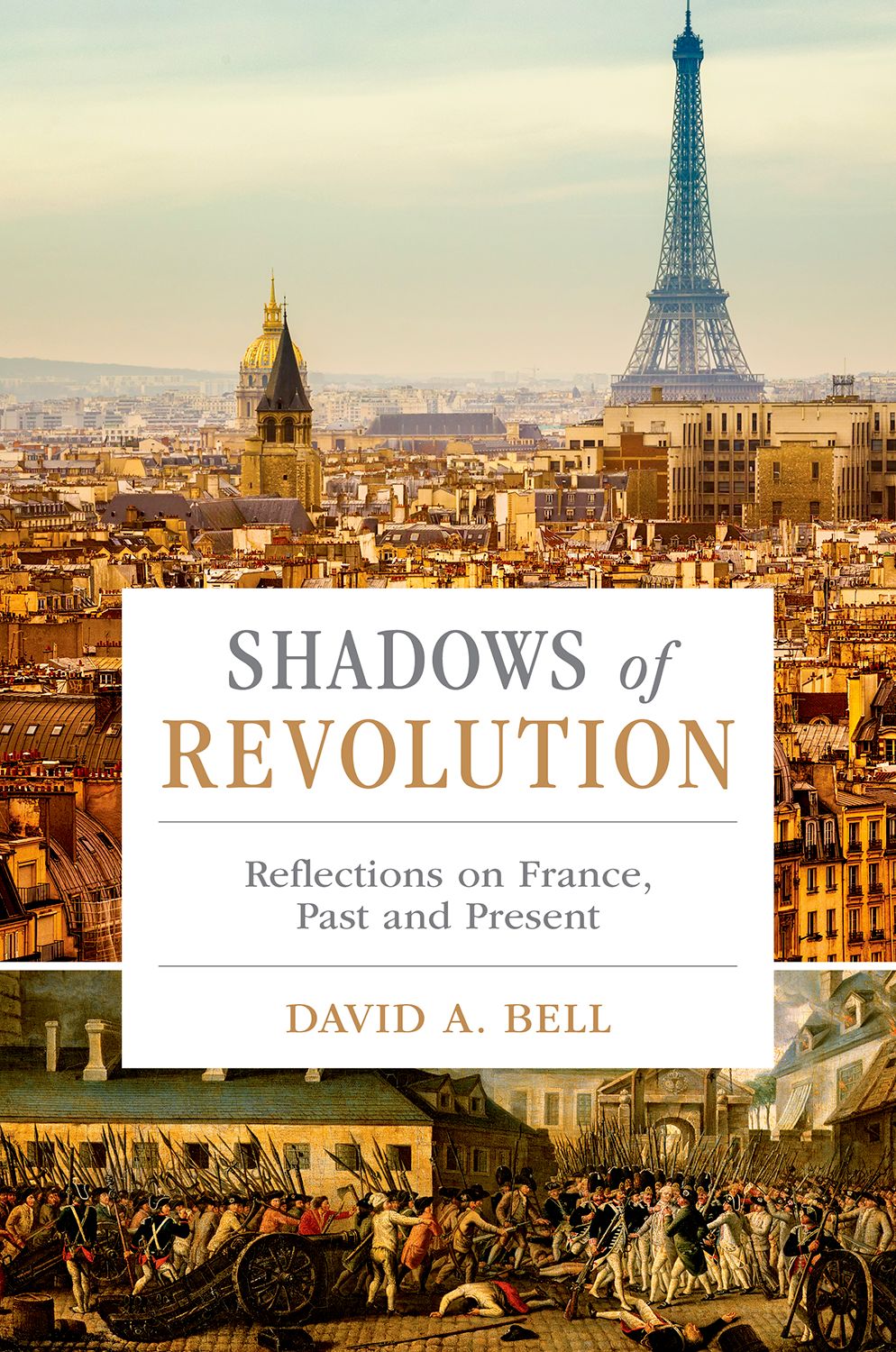

Shadows

of

Revolution

Books by David A. Bell

Lawyers and Citizens: The Making of a Political Elite in Old Regime France, Oxford University Press, 1994.

The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 16801800, Harvard University Press, 2001.

The First Total War: Napoleons Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It, Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

Napoleon: A Concise Biography, Oxford University Press, 2015.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of Americ

David A. Bell 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form, and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bell, David Avrom.

Shadows of revolution : reflections on France, past and present

/ David A. Bell.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780190262686 (hardback : acid-free paper)

ebook ISBN 9780190262709

1. FranceHistory. 2. FrancePolitics and government.

3. FranceHistoryRevolution, 17891799Influence.

4. National characteristics, FrenchHistory.

5. Politics and cultureFranceHistory.

6. FranceSocial conditions. I. Title.

DC38.B39 2016944dc23 2015011667

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

In memory of Paul Lemerle, and for his family

Contents

Shadows

of

Revolution

The entrance to the cole Normale Suprieure, Paris. On the round window are written the words: By Decree of the Convention, 9 Brumaire, Year III. Photo by Patrick Luiz Sullivan de Oliveira.

The essays in this book were written over more than a quarter of a century. For the most part, I wrote them in response to a particular book or political event, rather than to be parts of a larger project. But at the same time, in each one I drew on an engagement with France and its history that has consumed me through all of my adult life, and in the course of which I have developed some fairly consistent ideas and points of view. The essays gave me the chance to refine and develop those ideas and points of view. I hope the reader will have no trouble recognizing what binds this book together, but in this Introduction I would like to offer some more explicit thoughts about the books common themes and how I came to them.

I can date the beginnings of my serious engagement with French history very specifically: to September 1983, when I arrived in Paris to spend a year as a visiting student at the cole Normale Suprieure. I was then twenty-one years old, fresh out of college, and excited and apprehensive in equal measure. I knew the coles impressive reputation as an institution of higher learning. Its alumni roll could be mistaken for a hall of fame of French thinkers, from Louis Pasteur and mile Durkheim to Jean-Paul Sartre, Raymond Aron, Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, and Jacques Derrida. I felt comfortable in France, where I had spent two summers and made close friends. I had learned French well. Yet I had never set foot in the coles venerable buildings at 45, rue dUlm in the fifth arrondissement and had not met a single student or faculty member.

My initial impressions of the place did not do much to relieve my apprehension. The cole bears very little resemblance to the American college campuses I had known, consisting as it does of a series of nondescript large buildings crammed together around a few narrow streets in the heart of the Left Bank. Its public spaces seemed mostly to consist of endless, gloomy corridors, with lights on timers that always seemed to switch off at the wrong moment, leaving me fumbling in the dark. The dorm rooms were tiny and shabby, the bathrooms equipped only with toilettes turquesflushable holes in the floor (renovations have since improved matters somewhat). In lieu of anything resembling a printed catalogue, course offerings were announced on small handwritten notices pinned to bulletin boards. The French students I met in my first few days seemed singularly uninterested in getting to know a well-meaning if somewhat clueless American visitor.

Yet over the following weeks and months, my mood improved. I found and bonded with other foreign students, and started to become friends with French students as well. A kindly history tutor, Philippe Boutry, helped me design a program of study for the year. My first visit to the street market in the nearby rue Mouffetard, where the smells wafting from the cheese shops left me pleasurably dizzy with hunger, convinced me that the coles location more than made up for its subpar amenities (over the next year I gained fifteen pounds and did not regret a single ounce of them). I bought a monthly Metro pass and zoomed around the city to my hearts content, feeling very Parisian.

I also started to feel a powerful new connection to the French past. I had come to the cole to study history, and everywhere in Paris history seemed to press itself on me. In one of my courses, the instructor, Boutry himself, spent a lecture describing Pariss medieval fortifications, and then casually remarked to the students that we should go out the door, and turn right, left, then right again. After class I did so, and there, spilling onto the sidewalk of the rue Clovis, was a ruined section of the stone city wall built by King Philippe Auguste nearly eight centuries earlier. A few days later, a classmate took me down the old Roman road that was the rue Saint-Jacques to a sight most visitors to Paris never see: a real Roman arena, the Arnes de Lutce, nearly two thousand years old. Another short expedition, just a couple of stops away on the Metro, led to the eeriest tourist attraction Paris has to offer: the catacombs. In a series of dark tunnels, far below the surface of the city, lie the bones of literally millions of Parisians, exhumed in the nineteenth century from older mass graves and carefully stacked in neat, macabre piles: femurs and ribs and vertebrae, and rows on rows of sightless staring skulls.