Published in 2016 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2016 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J. E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Jeremy Klar: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Michael Moy: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Introduction and conclusion by Emily Swanson.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The French Revolution, Napoleon, and the Republic: libert, galit, fraternit/edited by Jeremy Klar.First edition.

pages cm.(The age of revolution)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6804-8025-2 (eBook)

1. FranceHistoryRevolution, 1789-1799Juvenile literature. I. Klar, Jeremy.

DC148.F726 2016

944.04dc23

2014038138

Photo credits: Cover, p. 1 DEA Picture Library/Getty Images; pp. xii, 5051 Heritage Images/Hulton Fine Art Collection/Getty Images; pp. 4, 66, 67, 127 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.; p. 7 Leemage/Hulton Fine Art Collection/Getty Images; p. 13 Musee de la Marine, Paris, France/De Agostini Picture Library/M. Seemuller/Bridgeman Images; p. 14 DEA/M. Seemuller/De Agostini/Getty Images; pp. 17, 46 AISA - Everett/Shutterstock.com; pp. 20, 55, 91, 111 Photos.com/Thinkstock; pp. 2627, 125 Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; pp. 3031, 75 Private Collection/ Look and Learn/Bridgeman Images; pp. 32, 95 Classic Vision/age fotostock/SuperStock; p. 37 Leeimage/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 39 National Gallery of Art, Washington, Timken Collection; pp. 64, 86 Private Collection/Bridgeman Images; p. 81 Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 105 DeAgostini/SuperStock; pp. 112113 Jastrow; p. 117 DEA/A. Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images p. 133 Print Collector/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

CONTENTS

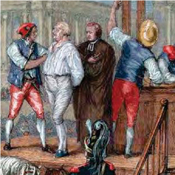

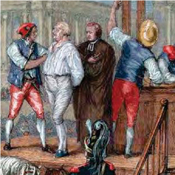

O n the morning of July 14, 1789, a Parisian crowd advanced on the Bastillea medieval fortress on the east side of Parisdemanding the release of the arms and munitions stored there. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Bastille had become not only a state prison and a place of detention for important persons charged with various offenses. Beyond its role as a prison, the Bastille had also become a symbol of the despotism of the ruling Bourbon monarchy. Angered by the prison governors evasiveness, the people stormed and captured the placean action that came to symbolize the end of the French monarchic regime and its social institutions.

The French Revolution is considered by most historians to mark the definitive end of the premodern era in France. Although the revolutionary fervour began in 1787, it reached its definitive climax in 1789 with the fall of the Bastille, and did not end until the late 1790s with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. Inspired by the Enlightenment ideas of such philosophers as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Ren Descartes, the French revolutionaries overthrew the oppressive systems of feudalism and absolute monarchy in favour of secularized individualism, representative government, and constitutionally defined inalienable rights.

While it is largely remembered for its devolutions at times into infighting and what essentially amounted to bloodbaths, the French Revolutions true impact was its influence in giving form to our modern understanding of democracy and citizenship. The French Revolution sent a message not just through France but in fact to the whole world that the essential sovereignty of the individual and the political might of the masses could not be ignored.

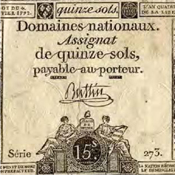

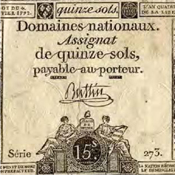

With the fall of the Bastille in 1789, the French Revolution was undeniably underway, however, the revolution was not born overnight; it was in fact the culmination of decades of political unrest and economic instability. The French economy had been devastated by the excessive spending of Louis XVI and the countrys involvement in the American Revolution. While providing aid to American revolutionaries enhanced French prestige, the country won no land or economic gains through their involvement, and as a result, France was burdened with loans it couldnt repay and, a seriously battered economy.

The peasant class had also endured years of severe famine and economic hardships brought on by droughts and a particularly violent hailstorm that devastated the countrys crops. An unusually cold winter in 1788 caused rivers to freeze, slowing the trade and transport of flour and other staples. As a result, the price of breadthe main form of sustenance for most of the populationnearly doubled. The immediate threat of food shortages and the economic disenfranchisement of the peasants, combined with changing understandings of citizenry and a public inspired by Enlightenment philosophy, set the stage for revolution.

By the fall of 1786 peasant riots had begun to spring up throughout the countryside. In an attempt to appease the lower classes and prevent outright revolution, King Louis XVI assembled the Estates-Generala protodemocratic body comprised of members of the clergy, nobility, and the bourgeoisieand invited its representatives to present their grievances to the court. Unfortunately, and perhaps unavoidably, dissent among the three orders of the Estates-General devolved into arguments and stagnation. As a result the nonaristocratic Third Estatewhich represented a hugely disproportionate majority of the countrys populationbegan to mobilize independently to support their goals of equal representation and direct representation.

In June 1789, fearing that they would be overruled by the two privileged orders in any attempt at reform, the deputies of the Third Estate led in the formation of the revolutionary National Assembly. The creation of the National Assembly signalled the end of representation based on the traditional social classes. The new organization gathered at an indoor tennis court and vowed not to leave until they had created a constitution for a new France. Despite their initial resistance, the majority of the noble members of the Estates-General ultimately joined the National Assembly, and Louis XVI was forced to recognize the new political body, albeit reluctantly.