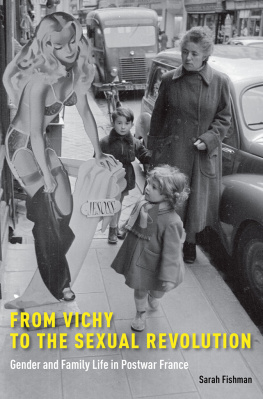

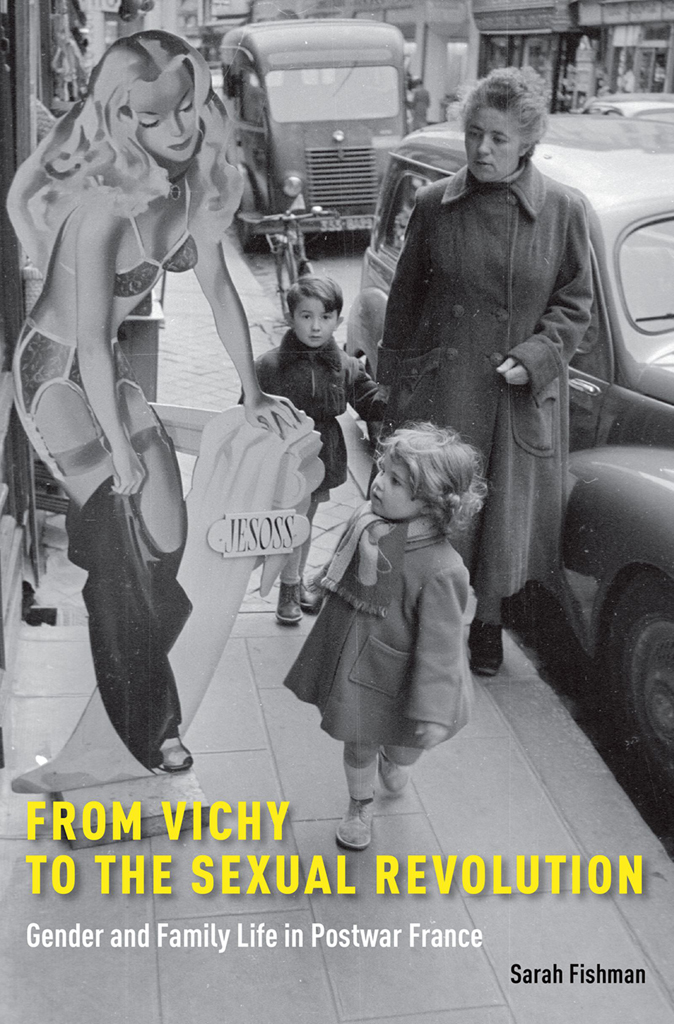

FROM VICHY TO THE SEXUAL REVOLUTION

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190248628

eISBN 9780190248642

To Andy

CONTENTS

It is a pleasure to acknowledge again my huge debt, intellectual as well as personal, to two people who have mentored me throughout my career, Patrice Higonnet and Dominique Veillon, remarkable historians and human beings, models for us all.

My friend and colleague Kathleen Kete has sharpened my thinking since we started graduate school as we shared ideas about our work. In particular, her work on the self sparked me to consider how new notions of the self in the postwar era of affluence were central to many of the changing ideas about relationships within the family.

Here at the University of Houston I have been fortunate to have amazing colleagues who have not only encouraged me but also taken the time to read and comment on drafts of various parts of my work, Robert Zaretsky, Karl Ittmann, Hannah Decker, and Bailey Stone. Hannah may not realize it, but her offhand comment about Freud as I struggled to understand new interest in fathers after the war represented a truly clarifying moment. Thanks to the students, graduate and undergraduate, at the University of Houston, and especially Phuong Nguyen, Katie Streit and Dan Le Clair, for their valuable feedback at the colloquium.

I am also extremely grateful to the University of Houston for supporting me with several small grants that enabled me to travel to France to do archival research. The College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences granted me a Faculty Development Leave, allowing me the time to write. I must also thank my fellow travelers, present and former deans and associate deans John Antel, Cathy Patterson, Joe Pratt, Cynthia Freeland, and Steven Craig, Anadeli Bencomo and the entire staff of the office, Andrea Short, Anna Marchese, Juanita Terrell, Micki Miles and, from Academic Affairs, Janie Graham, dont know what Id do without you, Jyoti Cameron and Chadi Lewis, you too! My heartfelt thanks specifically to John W. Roberts for his constant support, both personal and professional, while he served as dean of the college.

Rachel Chrastil kindly provided many helpful comments in particular about the polling of young unmarried women. The work and friendship of historians Joelle Neulander and Judy Coffin have always been an inspiration. Thanks to the WWBD gang, including the late and much missed Donna Ryan, life coach Barry Bergen, Steve Zdatny, and Kolleen Guy. Bruno Cabanes and Guillaume Piketty, the organizers of the colloquium Retour lintime in Paris, encouraged me to return to my research on POW wives. So many of my fellow French historians have had an impact on my work and thinking, Sandy Ott, Brett Bowles, Ken Mour, Paula Schwartz, Miranda Pollard, Lisa Greenwald, Shannon Fogg, Jonathyne Briggs, Steve Harp, Manon Pignot, Ludivine Bantigny, Mary-Louise Roberts, Alice Kaplan, Steve Zdatny, Richard Vinen, Richard Jobs, Rebecca Pulju, Simon Kitson, Kristen Stromberg Childers, Alice Conklin, Brian Newsome, Nicole Rudolph, Robert Nye, and Ed Berenson. French historians are wonderful group; Im so happy to be a member of this family!

In addition to published sources at the BNF, this book also rests on archival sources that required special permission to consult. I must express my most sincere appreciation for their help and support to the archivists and staff at the four different departmental archives, Paris, the Drme, the Bouches-du-Rhne, and the Nord. Many thanks also to Marianka Louwers, Yasmina Guerfi, Vronique Grall, and Jean-Victor Auclair Prvost for their assistance in tracking down and granting permission to use images.

In France, Annette Becker and Genevive and Yves Dermenjian provided me not only with places to stay in Lille and Marseilles but with intellectual enlightenment and wonderful companionship. Thanks to Pascal Poulain and Thierry Zabal for being great friends. Isabelle LeCoufle and her amazing, loving, and boisterous family provide me with a home away from home and an intensive immersion totale whenever I arrive in Paris; you have no idea how much it means.

Anonymous reviewers comments proved most helpful as I undertook final revisions to the manuscript. This book has benefitted tremendously from the clear and perceptive guidance of Nancy Toff at Oxford University Press.

Finally, thanks to my family for putting up with my long absences, believing me when I told them it was work. Andy, I could never have done any of this without you, and Alex and Katy, none of this would have made any sense without the two of you! I love you.

Twenty-one years later, Laura wrote to Confidences for advice, asking, Are all men retrograde, jealous and not with the times? Lauras husband married her knowing she worked as a model, but after the honeymoon she returned to work, and ever since scenes have been multiplying. Is this what marriage is all about? I am profoundly disappointed. In response, the advice columnist speculated that Lauras husband could fall into the category of those who prefer that their wives stay at home. That is his right. But you also have the right not to share his somewhat selfish opinion.

This book examines how and why ideas about womens and mens lives, gender roles for men and women, courtship, love and marriage, spousal relations, parenting, childhood, and adolescence changed in the twenty years from Frances liberation in 1944 to the mid-1960s.

Frances situation looked particularly dire just after World War II. Air raids and combat left much of the country in ruins. Political divisions ran deep. The war and immediate postwar years witnessed the apotheosis of profound political divisions in France that dated back to the 1789 Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, France remained divided into two long-standing, broad camps. On one side stood the monarchist, anti-republican right that rejected democracy and equality, feared outsiders, resisted social change, and insisted on the need to shore up authority and fatherhood. On the other side, a pro-republican left favored democracy, political equality, and individual rights. A decade after the establishment in 1870 of the Third Republic, the republican left triumphed politically over the monarchist, authoritarian right. However, over its seventy-year lifespan, the Third Republic experienced periodic profound crises that threatened its stability and at times, seemingly, its very survival. At the start of the Great War in 1914, in a rare show of patriotic unity, both left and right had put aside their differences to form the so-called sacred union. But that brief unity fell apart after the wars end. If anything, division intensified throughout the 1920s and 1930s as new political parties formed on the extremes, the Communist Party on the left and several fascist parties on the right. The increased polarization left France unstable, immobilized in the face of growing domestic and international difficulties. However, unlike its neighbors to the east, while France cycled rapidly through governments as it struggled to deal with the Great Depression, political unrest, and intensifying foreign crises, the Third Republic survived in France until military disaster brought it down in 1940.