Religion and Resistance in Appalachia

Religion and Resistance in Appalachia

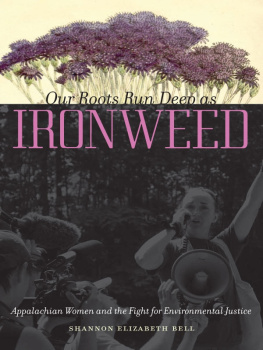

Faith and the Fight against Mountaintop Removal Coal Mining

JOSEPH D. WITT

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2016 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Photographs by Joseph D. Witt.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-6812-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6813-5 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6814-2 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

In the Gospel of Matthew in the seventeenth chapter,

it says if we have the faith of a mustard seeda tiny mustard seed

if we have that kind of faith, we can move mountains!

I will tell you today, that we have the faith of a mustard seed

NOT to move mountains! You, all of you here today,

represent tiny mustard seeds and you are making a difference!

Reverend Jim Lewis, Marsh Fork Elementary School,

Raleigh County, West Virginia,

June 23, 2009

Contents

Introduction

Marsh Fork Elementary, June 23, 2009

In the summer of 2009, I participated in a rally against mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia. The rally was held on the grounds of Marsh Fork Elementary, a school situated between the Coal River and Route 3 in Raleigh County, West Virginia. Sitting immediately below a slurry impoundment (a giant reservoir of toxic coal sludge produced by the coal preparation process and retained by an earthen dam), Marsh Fork Elementary also sat at the center of many debates surrounding the safety and justness of mountaintop removal. Activists cited increased health problems for Marsh Fork students due to their proximity to an active strip mine, such as abnormally high rates of asthma, and worried about the potentially disastrous consequences of any stresses or failures in the earthen dam retaining the slurry. The nearby mine and processing plant were owned and operated at the time by Massey Energy, one of the most controversial coal companies in the region. It was led by Don Blankenship, an outspoken and active opponent of labor unions and environmental regulations. Both Blankenship and his company were frequent targets for environmentalist outrage, and for his part, Blankenship seldom passed an opportunity to denounce tree huggers and others who, so he claimed, would destroy the jobs of hard-working Appalachian miners. In 2012 a new elementary school was built several miles from the original site, thanks to donations and ongoing political pressure; but in June 2009 these issues remained unsettled.1

As I approached the rally that morning I was surprised to see the highway lined with people, shouting and brandishing signs with statements like Massey Wives Support Our Miners and WV Miners Say Go Home Tree Huggers (see ). These were procoal industry counter-protestors who had come there in response to the publicly advertised antimountaintop removal rally. Perhaps noticing my Florida license plate (where I was then living), a small number among the counter-protestors leaned toward my car as I drove slowly by, shouting Go home! and making obscene gestures. This was a surprising introduction to the intensity with which local Appalachians viewed the coal industry and those who would oppose it. I was truly unprepared for such a large number of intimidating counter-protestors.

Figure 1. Pro-coal counter-protestors at Marsh Fork Elementary, Sundial, West Virginia, June 23, 2009.

After finding a spot to park along the side of the road, I walked to the school grounds, where the antimountaintop removal activists had set up a small stage and were preparing to begin the rally. I noticed Judy Bonds and Sage Russo, two West Virginia activists who had both encouraged me to attend the rally when I had met them earlier that year. I also noticed the familiar faces of Larry Gibson, the Keeper of Kayford Mountain; Maria Gunnoe, who, like Judy Bonds, would eventually be awarded the prestigious Goldman Prize for grassroots environmentalism; and Ed Wiley, the grandfather of a Marsh Fork student whose Pennies of Promise campaign had helped raise concern for the situation at the school. Dozens of people mingled around the stage wearing clothing and paraphernalia identifying them as mountaintop removal opponentspins that stated Stop Mountaintop Removal; shirts from the local environmental organization, Coal River Mountain Watch, reading, Save the Endangered Hillbilly; and the neon yellow t-shirts and hats characteristic of Larry Gibsons Keeper of the Mountains Foundation. A man dressed as Uncle Sam with an exaggerated prosthetic nose loped around the field on stilts. Outside the group of mountaintop removal opponents, men wearing the characteristic blue and orange miner uniforms gathered in groups. Some revved their motorcycles nearby to drown out the rally speakers. A musician with the antimountaintop removal group played banjo on stage while pro-mining counter-protestors criticized his technique and goaded him to play Coal Miners Daughter (Loretta Lynns popular country song about growing up in a mining community in eastern Kentucky). Reverend Jim Lewis, an Episcopal priest in Charleston, West Virginia, and Denise Giardina, an award-winning West Virginia author and ordained Episcopal deacon, walked through the crowd in the white collars and black shirts characteristic of their religious positions. At the same time a middle-aged man in a miner uniform stood at the edge of the crowd and chanted, God gave us the trees so we could be happy, among other sometimes indecipherable statements, in the rhythmic style of Pentecostal preachers. Hollywood actress and environmental activist Daryl Hannah and NASA climatologist James Hansen addressed the crowd about the dangers of climate change and the need to end fossil fuel dependency. A local American Indian activist, preachers such as Lewis and Giardina, and leaders of environmental organizations spoke as well. They were all met by the jeers, shouts, and air horns of counter-protestors. At one point the PA system came unplugged, to which many counter-protestors in the crowd yelled, There, we cut your coal off! Ken Hechler, a long-serving West Virginia politician who was then in his nineties, spoke about the need to continue to protect miners and their families from exploitation by the coal industry. As Hechler spoke, the loud counter-protestors drifted away, leaving a striking calm to the end of the rally.

Next page