WORSE THAN

THE DEVIL

Anarchists, Clarence Darrow, and

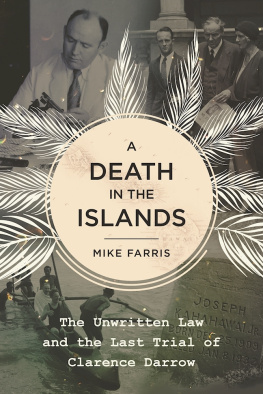

Justice in a Time of Terror

Dean A. Strang

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2013 by Dean A. Strang

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Strang, Dean A.

Worse than the devil: anarchists, Clarence Darrow, and

justice in a time of terror / Dean A. Strang.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-299-29394-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-29393-2 (e-book)

1. Trials (Riots)WisconsinMilwaukeeHistory20th century.

2. Judicial corruptionWisconsinMilwaukeeHistory20th century.

3. Darrow, Clarence, 18571938.

4. AnarchistsWisconsinMilwaukeeHistory20th century.

5. Italian AmericansWisconsinMilwaukeeHistory20th century.

6. Bay View (Milwaukee, Wis.)History20th century.

7. Milwaukee (Wis.)History20th century. I. Title.

HV6483.M55S77 2013

345.7750243dc23

2012032689

In memory of

Alma Sieber Strang

Catharine McClelland Wedge

Per (Paul) Strang

Arthur H. Wedge

Contents

Worse than the Devil

Illustrations

Preface

Usually, Chicagos Haymarket Square comes to mind first when the topic of radicals on trial arises or when we ask how justice fares in the heated atmosphere of political struggle, fear of foreign-born agitators, and grief over lives lost. Just maybe, though, events that took place ninety miles north of Chicago and thirty years after the Haymarket tragedy offer an even better moment for considering those questions. More police officers died in a Milwaukee bombing in November 1917 than died in the May 4, 1886, bombing in Chicago. Several of the Chicago defendants were immigrants; all of the Milwaukee defendants were. And, while both cases concerned anarchism, the dominant radical (and sometimes violent) ideology of that era, the Milwaukee case arose in the early months of this countrys direct participation in an unprecedented world war, when the country was awash in nativist sentiment, patriotism, and intolerance of dissent.

The trials themselves provide even sharper contrast. After the bomb exploded in the ranks of police officers who were clearing Haymarket Square, the ensuing trial in Chicago directly concerned responsibility for that bombing. And that trial may not have been the failure that conventional wisdom has had it for decades. The Milwaukee trial was different. It was but a proxy proceeding in two senses.

First, police and prosecutors never charged anyone with making or planting the bomb that eventually exploded in an assembly room at Milwaukees central police station. The trial that began the very next week nominally concerned only a separate event, a disturbance in an Italian neighborhood that had resulted in gunplay and death more than two months before the bomb destroyed much of the police station. Because the trial began in Milwaukee just three days after that city buried nine fallen police officers whose deaths otherwise went unvindicated, it became a proxy for the bombing trial that never would be.

Second, the eleven defendants themselves were proxies for their supporters whom the public, police, and mainstream newspapers widely blamed for the bombing. When someone planted the bomb, these eleven already were in jail awaiting trial on the separate events two months earlier. Jail is exactly where they had been since that melee. They could not have made or planted the bomb had they wanted to. But because the intended target of the bomb was the man at the center of the neighborhood disturbance, an antagonist of the eleven defendants, it was easy, even natural, to assume that supporters of the eleven were responsible.

Even if not the travesty that many think, Chicagos Haymarket trial surely included a kind of corruption of the justice system. That corruption is the sort that festers in any opportunity for the selfish ambitions of lawyers and judges to overtake the selflessness that their official duties high-mindedly suggest. In the light of intense public interest, judges sometimes strut a path that they hope will lead to higher office, prosecutors preen for the same reason, and both defense lawyers and their clients resort to political theater designed to advance their personal fame or broad causes rather than their legal interests. The Milwaukee story includes corruption of the justice system in the same sense and possibly to an even greater degree. Specifically, it ends in an appeal that leaves one queasy even today. No less than Chicagos own Clarence Darrow is a central figure in that unsettling appeal.

This book explores all of this.

Uncoupled from its day and details, the books story is a parable of the human frailty that necessarily weakens every link in any system of justice, including ours today. In its own time, the story concerned immigrants who were real or suspected anarchists. Thirty years later, after the next world war, it would have concerned actual and suspected communists, many of them also immigrants or the children of immigrants. Today, it might concern actual and suspected Islamist radicals, who again often are immigrants, the children of immigrants, or watching the West (and the United States especially) from afar.

So the accidental details of characters, creed, and catalyst change over time. But the underlying flaws, even failings, of our institutions of criminal justice stubbornly resist rectification. In a land that proposes to dispense equal justice under law, the alienated newcomerthe other, whoever he or she is in a given dayremains at real risk of an outcome that has little to do with individual justice or even fair process and much to do with assuaging public fear and venting anger. The prejudices, superstitions, and plain fears that animated police officers, prosecutors, judges, and juries a century ago all persist today. Now, more than ten years after the September 11 attacks and the sometimes repressive or lawless responses of our institutions of criminal justice to those events, the parable is worth telling and remembering.

Beyond its value as parable, this story also has concrete historical importance. The most significant aspect is a previously unknown episode in which Americas greatest trial lawyer, Clarence Darrow, perhaps tried directly to corrupt the justice system. Questions about Darrows ethics and tactics are not new. He stood trial twice in Los Angeles on juror bribery charges after the 1912 McNamara brothers prosecution, and there are other documented, if hazier, incidents in which allegations arose about the lawfulness of his work. But no biographer or researcher ever has raised a question about his role in the 1918-19 appeal from the Milwaukee convictions of eleven Italians. While the evidence is not conclusive, it also is not weak: it begins with the sworn testimony of an ex-prosecutor who directly implicated himself in the illegal plot and continues with some corroboration of that lawyers testimony.