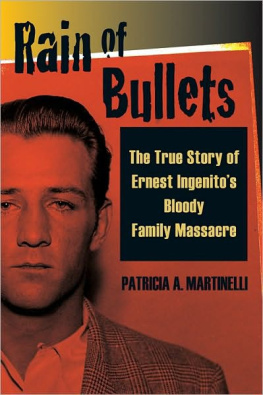

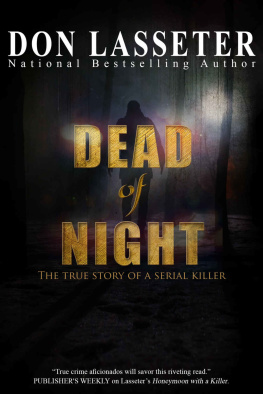

PATRICIA A. MARTINELLI

To the victims and the survivors of domestic violence with my deepest respect

Principals

The Ingenito Family

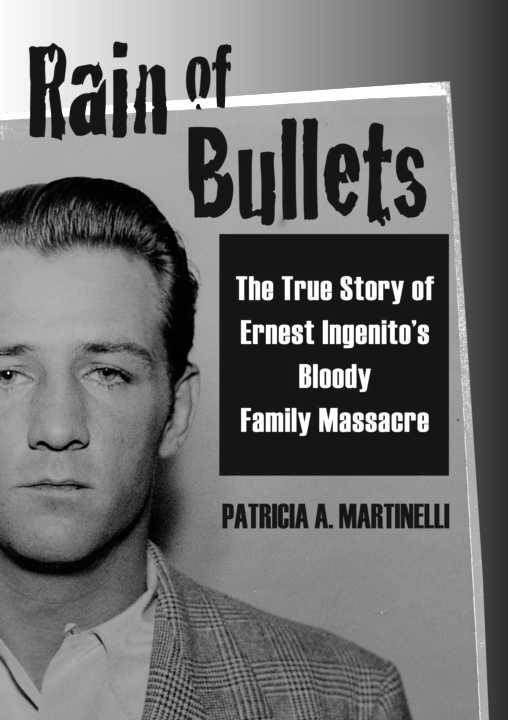

Ernest "Ernie" Martin Ingenito, the accused

Theresa "Tessie" Mazzoli Ingenito, his wife

Michael Ingenito, their older son

Ernest Ingenito Jr., their younger son

The Mazzoli Family

Michael "Mike" Mazzoli, Tessie's father

Pearl "Pia" Pioppi Mazzoli, Tessie's mother

Frank Mazzoli, Mike's younger brother

Hilda Patella Mazzoli, Frank's wife

Nola Mazzoli, older daughter of Frank and Hilda

Barbara Mazzoli, younger daughter of Frank and Hilda

Frank Mazzoli, son of Frank and Hilda

The Pioppi Family

Armando Pioppi, Tessie's grandfather

Theresa Biagi Pioppi, Tessie's grandmother

John Pioppi, Tessie's uncle

Jino Pioppi, Tessie's uncle

Marion Volpa Pioppi, Jino's wife

Jeannie Pioppi, older daughter of Jino and Marion

Teresa Pioppi, younger daughter of Jino and Marion

Armando "Mando" Pioppi, son of Jino and Marion

Other Family Members

Dominick Biagi, Tessie's maternal grandmother's brother

Eva Biagi, Dominick's daughter

New Jersey State Police Investigators

Capt. Howard Carlson

Lt. Hugh Boyle

Lt. Julius Westphalen

Sgt. George T. DeWinne

Det. Sgt. William Conroy

Det. Cpl. William B. Piana

Det. Frank Morrisey

Det. Carl Dereskwicz

Tpr. Leonard Cunningham

Tpr. Nicholas Fagnino

Tpr. Herbert Kolodner

Tpr. John Kurtland

Tpr. Raymond Vorberg

Tpr. George Yeager

Additional Law Enforcement Officials

George Small, Investigator, Gloucester County Prosecutor's Office

George H. Stanger, Prosecutor, Cumberland County

Judges

Judge John B. Wick, Gloucester County Superior Court

Judge Elmer B. Woods, Superior Court Assignment Judge

Prosecuting Attorneys

E. Milton Hannold, Prosecutor, Gloucester County

Guy Lee Jr., Prosecutor, Gloucester County

Rowland B. Porch, Assistant Prosecutor, Gloucester County

Emory Keiss, Assistant Prosecutor, Atlantic County

Defense Attorneys

Herbert H. Butler

Charles Cotton Camp

Louis B. LeDuc

Frank Sahl

Philip Shick

Wellford H. Ware

On the night of November 17, 1950, Ernest Ingenito went on a shooting rampage against his in-laws, killing five people, wounding four others, and affecting the course of many lives with his actions. The shootings occurred in South Jersey, an idyllic place to live at that time. A small population was stretched across miles of rural countryside, and everybody knew everybody else. Very few people had money, but that was all right; chances were good most of your neighbors were in the same boat. Nobody locked their doors. Most kids had open fields to run in and cool streams to splash in when they weren't playing games. Adults generally spent their free time watching television, reading magazines, or talking to one another. Occasionally, everyone might pile into the family car and go for a ride that sometimes ended at the local Stewart's for a round of hot dogs and frothy Black Cows. Violence of this type was something that happened elsewhere, usually in "the city." At the same time, such tragedies were simply not as commonplace as they are now, whether you lived in the city, suburbs, or country. Was it a more innocent time? Of course not. Did it feel like it was? You bet.

I had grown up in South Jersey knowing the bare bones of this story, because it was related, literally through marriage, to my own extensive family. Like most kids, I gave it only nominal attention; for me, there were so many other, more important things to worry about in those days. But in recent years, as I began to write about crime on a regular basis, it seemed like a subject that deserved further exploration for a number of reasons. As a former newspaper reporter who for many years had covered similar stories in the region, I recognized this case as a classic example of what happens when domestic violence explodes.

In addition, telling this story gave me, a second-generation Italian-American woman, a chance to explore the world of the Italians and their children who settled in South Jersey in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Having grown up very close to my roots, which ran deep throughout the area, I have written about a world in which I feel comfortable. In this book, I specifically address the perspective of the Italians of South Jersey, because they were primarily involved in what happened, and because their life experiences colored the events accordingly. The immigrants and their children were a very close-knit group of people; their descendants, even sixty years later, remain the same, often reluctant to discuss on the record what happened all those years ago. When they did talk, passions were sometimes still as strong, as if the murders and assaults had occurred the day before.

Finally, I felt it was important to tell this story because it reveals, at its heart, just how complex human beings are as a species. As a student of history, I have always been fascinated by human behavior. I am not pretending, however, that this book will resolve any of the questions that have plagued civilization since the beginning of time. I doubt that anyone will ever really know the contents of another person's heart, let alone understand why we are unable to treat each other better during the short time we are here. I do not spend a lot of time theorizing about why Ernest Ingenito decided to pick up his guns and start shooting that night. I do not make judgment on his morality, character, or sanity. I will let each reader make up his or her own mind on the matter.

Many of the people who were directly involved in the case passed away before I began my research. Fortunately, their memories live on through others, who were kind enough to share their perceptions about those friends, colleagues, and family members who are no longer here to speak for themselves. Many records remain-some generated by Ernest Ingenito himself-allowing me to reconstruct the chain of events that occurred in the weeks preceding the night of November 17, 1950, and the trials that came afterward. Not surprisingly, there are a few gaps, but none, I think, that have an adverse affect on the story. I have kept the courtroom testimony in the order it was presented, but some of it has been condensed to avoid repetition and irrelevancy. I was not concerned about the number of stenographers who were present in court each day. Sometimes, I left witnesses out completely. This is because I wanted to tell a story and avoid sounding like a trial transcript. For the record, the prosecution called more than forty witnesses to testify against Ingenito; the defense attorney called eight, including the accused, to speak on his behalf.

Sadly, a lot of questions were raised about this incident that may never be adequately answered. Besides the obvious one-why did he do it?-I had difficulty trying to figure out the prosecution's reasons for the way it initially presented the case. In light of the seriousness of the crimes, I was unable to understand why Ingenito received the sentences that he did, which resulted in his serving a relatively short time in jail. I was truly surprised to learn that he was never prosecuted for any of the assaults on those who survived. Even some of the legal experts I consulted were puzzled as to why Ingenito was spared from the electric chair at a time when other murderers, some of whom had killed only one person, received the ultimate punishment. For example, Howard Auld, a thirty-oneyear-old former paratrooper and chauffeur from Bellmawr, was executed in the electric chair at 8:06 P.M. on March 27, 1951, at the New Jersey State Prison in Trenton. He received this sentence in 1945 for the brutal murder of one woman, twenty-three-year-old Margaret McDade, a waitress from Philadelphia who had refused his advances.