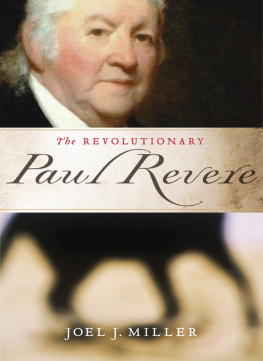

Joel Barlow

Joel Barlow

JOEL BARLOW

American Citizen in a Revolutionary World

RICHARD BUEL JR.

2011 Richard Buel Jr.

All rights reserved. Published 2011

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Buel, Richard, 1933

Joel Barlow : American citizen in a revolutionary world /

Richard Buel Jr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8018-9769-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8018-9769-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Barlow, Joel, 17541812. 2. Poets, American18th centuryBiography.

3. DiplomatsUnited StatesBiography. 4. PoliticiansUnited

StatesBiography. I. Title.

PS705.B84 2011

811.2dc22

[B]

2010017552

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book.

For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936

or .

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible. All of our book papers are acid-free, and our jackets and covers are printed on paper with recycled content.

For those in the Wesleyan community

who have supported my scholarly career

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction

Picture the crowded, still medieval city of Algiers in July 1796. Joel Barlow had recently accepted appointment as the U.S. consul there, at the urging of his long-time friend and fellow Yale graduate, David Humphreys, then U.S. minister to Portugal. The administration of George Washington needed someone of Barlows stature to resolve an urgent problem. Before 1793 only a few American vessels venturing into the Mediterranean had fallen victim to North African piracy. But after Britain had arranged a truce between Algeria and Portugal toward the end of that year, armed vessels from the Barbary states started seizing American merchantmen in the eastern Atlantic and enslaving their crews. Pleas for help from the 150 American seamen incarcerated at Algiers had appeared in American newspapers.

Barlow and his wife had just returned to Paris after fourteen months residence in Hamburg, but the summons from Humphreys, a man Barlow had long admired, was hard to refuse. Both men feared that if the new U.S. government could not defend its citizens against enslavement, it would not be worthy of their allegiance. Though Britain posed a more immediate, strategic challenge to the United States, failure to free American citizens from North African slavery could seriously compromise the still fragile authority of the federal government.

Barlow brought unusual qualities to the job of U.S. consul. Though at home he was known for The Vision of Columbus (1787), his epic poem about America and its recent revolution, in Europe he had achieved notoriety as a defender of the French Revolution. His wholehearted endorsement of the revolutions early republican phase had led the National Convention to confer French citizenship on him in 1793. That status gave him a diplomatic advantage because France was the European power best able to influence the North African appendages of the Ottoman Empire. Barlow initially assumed his mission would take only a few months, but he soon found that being the American consul in Algiers was more taxing than he had expected. Commitments had already been made by Joseph Donaldsonan advance agentabout the payment of tribute to the dey of Algeria, which could not be fulfilled. To placate this impatient, capricious tyrant, Barlow resorted to expedients for which he lacked formal authorization. To compound his difficulties, the bubonic plague broke out three months after his arrival in Algiers.

The plagues seasonal appearance, later in 1796 than usual, was accepted by the Islamic denizens and rulers of the region as a visitation of Allah. Although a good Moslem was supposed to submit to such judgments, those who were able left the city for the countryside. Barlow could have taken this precaution, but it was not an option for the American sailors held prisoner in unhealthy conditions, some of whom contracted the disease. Barlow felt obliged to visit them and to render both the sick and the well any assistance he could, despite the risk of contracting the disease himself. In early July, Barlow drafted a long letter to his wife Ruth, who had remained in Paris. After explaining his situation, he warned Ruth that he might never return. But he was unlikely to unnecessarily alarm her because, as he noted, the letter would not come into your hands unless & untill by some other channel you shall have been informed of the event which it anticipates. Because Barlow assumed Ruth valued his life more than you do your own, as he did hers, he sought to explain the pressing duty of humanity he felt to expose my self... in endeavouring to save as many of our unhappy citizens as possible.... Though they are dying very fast, yet it is possible that my exertions may be the means of saving a number who otherwise would perish. If Barlow died in the course of helping them, he begged Ruth not to upbraid my memory by even thinking that I did too much.... [M]any of these persons have wives at home as well as I.... If their wives love them as mine does me (a thing which I cannot believe, but have no right to deny) ask these lately disconsolate and now joyful families, whether I have done too much.

Barlow found drafting this farewell letter difficult since he could think of no word of tenderness, of gratitude, of counsel, of consolation that could compensate for robbing you of, the husband whom you cherish. The only thing he could do, since they were childless, was to make Ruth his sole heir. He estimated his estate might come to as much as $120,000, from which Ruth would derive an annual income of between $5,000 and $7,000. That would make her richer than most other American women, whose claims on their husbands estates were usually limited to a dower third. Barlow had never been bound by the usual, but he felt obliged to explain to Ruth his reasons so that she could parry the criticism he expected his bequest to generate.

In a view of justice and equity, Barlow felt that whatever we possess at this moment is a joint property between ourselves and ought to remain to the survivor. When they had married, I was destitute of every other possession as of every other enjoyment. I was rich only in the fund of your affectionate economy and the sweet consolation of your society. Looking back upon our various struggles and disappointments, particularly since 1790when Ruth had joined him in EuropeBarlow marveled how often he had been rendered happy by misfortunes; for the heaviest were turned into blessings by the opportunities they gave me to discover new virtues in you, who taught me how to bear them. Barlow had become happier in [Ruth] during the latter years of our union because he had learned to love you better; my heart has been more full of your excellence, & less agitated with objects of ambition, which used to devour me too much. He attributed the acquisition of the competency which we seem at last to have secured... more to your energy than mine: I mean the energy of your virtues, which gave me consolation and even happiness under circumstances, wherein, if I had been alone, or with a partner no better than myself, I should have sunk. Since Ruth deserved to enjoy the fruits of our joint exertions with me.... if by my death you are to be deprived of the greater part of the comfort you expected, it would surely be unjust and cruel to give any portion... to others.

Next page