Copyright 2011 by Phil Rogers

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Triumph Books, 542 South Dearborn Street, Suite 750, Chicago, Illinois 60605.

Triumph Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

This book is available in quantity at special discounts for your group or organization. For further information, contact:

Triumph Books

542 South Dearborn Street

Suite 750

Chicago, Illinois 60605

(312) 9393330

Fax (312) 6633557

www.triumphbooks.com

Printed in U.S.A.

ISBN: 978-1-60078-519-1

Design by Sue Knopf

All photos courtesy of AP Images unless otherwise noted.

To Phyllis Merhige,

Katy Feeney,

Ernie Banks,

and pioneers everywhere

C ONTENTS

Index

F OREWORD

By Thomas Boswell

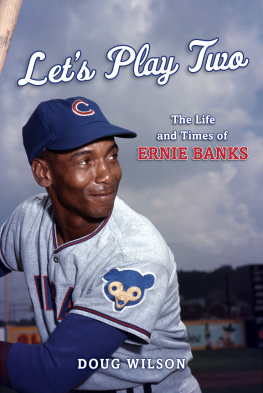

W hen we are sifting for childhood heroes, we look for what we lack. Even though I grew up in Washington, D.C., I looked all the way to Chicago to find Ernie Banks. Then I didnt let him go.

The late 50s were full of major sports heroes. I could have found something that appealed deeply to me in Johnny Unitas, Arnold Palmer, or Willie Mays. I certainly read enough profiles of all of them, and other stars, in every sports magazine. There were local D.C. heroes, like home run champion Roy Sievers, who I fell for hard as a kid. But with all the rest of sports to choose from, I picked Banks and followed his last 15 seasons avidly.

By 69, after I graduated from college, Ernie was the last childhood hero that I still rooted for every day. In September, as his Cubs battled Americas darling, the Miracle Mets, I clung to Banks, then 38, as he staggered toward his only chance to play in a World Series. When the Cubs failed, I took a lesson from their fallsupplied by Banksthat has never left me.

If you want a defining trait, one that survives defeat, attracts affection from others, and mysteriously restores itself, then its hard to beat enthusiasm.

Its a great day for a ballgame. Lets play two, isnt just a quotation thatll probably end up in Bartletts [Familiar Quotations]. Its philosophy.

Believe me, as someone whos covered baseball for 35 years at the Washington Post, nobody wants to play 324 games, not even Ernie. Lets play two, is a world view and a deep one, not a quip.

The outward joy that Banks professed, even if it was partly innate to his temperament, was also a daily act of will: a lifelong private commitment to enthusiasm as a guiding principle.

For countless people, including me, its hard to find anybody among family or friends whos a living example of that combination of attitude and energy. When you find a Banks who sticks to those guns all his life, thats the definition of a role model.

He who would be calm must first put on the appearance of calm, Shakespeare wrote. In other words, our emotions do not simply come from inside us and express themselves outwardly. The process can work in reverse. By putting on the outward appearance of calmor confidence or enthusiasm or whatever quality we valuewe can increase our tendency to feel that way.

Every day for 19 seasons, Banks put on that appearance of joy and convinced himself and probably some teammates that they were playing ball not so much competing as publicly scrutinized pros.

So how did that sensibility stand up to The Collapsethe epitome of the sport as pain, not play?

When the Cubs crashed in September, losing 11-of-12 to go from five games ahead to 4 behind, it all happened so fast that it seemed more grotesque than dramatic and, by the end, darkly comic. Banks slumped, too. But after seven straight losses, he made a personal stand. Against the Phils, he drove in a run in the first inning, then homered in the eighth to give the Cubs a 21 lead; they blew it, of course. The next day, in the only Cubs win of the whole smashup, Banks drove in four of their five runs. That was the old mans statementnot nearly enough, but something.

On the final day of the season, when manager Leo Durocher, the grouch who said, Nice guys finish last, was disengaged from his team and stuck with the disgrace of his defeat, Banks was still showing upjust to play baseball. On the seasons last day, Banks, the oldest man in the lineup, played his 155th game of the year and had a triple, a homer, and he drove in three runs to finish the season with 106 RBIs, a total he hadnt topped since his twenties.

You need all kinds of role models as you grow up. That 69 Cubs choke sealed it for meBanks would remain one of mine. No team could fail worse. Mostly, Banks stunk, too. But I didnt respect him any less. And nobody else seemed to, either.

By 77, Ernie had been voted into the Hall of Fame. Durocher got in by the back door of the Old Timers Committee in 94three years after he died. Banks has been going to Cooperstown every August for a third of a century, enjoying the chatter with his fellow immortals. Leo never got to sit on the veranda of the Otesaga Hotel overlooking Lake Glimmerglass and preen. Lets play two, or nice guys finish last? Excuse me, but I call it a parable.

In a baseball sense, Banks is an immortal because he averaged 41 homers and 115 RBIs per year as a shortstop from 195560, making himself the equal of Mays, Mickey Mantle, or anybody else in the game for those half-dozen years.

Thered never before been a middle infielder with such power. And to this day, there still hasnt. Banks won a Gold Glove, too. Switching to first base and remaining a solid hitter until hed amassed 512 homers assured him a place in the Hall.

But it is the Other Banks, the man who exemplified an entire stance toward how we approach life, who will be remembered long after most of baseballs 500home-run men are forgotten.

Perhaps fans of the 50s, when Banks emerged, were particularly susceptible to what he embodied. From 1929 through the early 50s, the whole country, and especially the Greatest Generation, endured a unique sequence of traumas from the Depression to World War II to McCarthyism.

The virtues that were required to survive those times were admirable but perhaps tended toward a narrow spectrum. My friends and I seemed to come from families whod all walked 20 miles to schooluphill both ways. My grandfather, a small-town farmer who almost went broke in the 30s, worked dawn to dusk. I saw him grab a snake out of a ditch, crack it like a whip, and throw it back dead. My father, an Army sergeant, was in the Normandy invasion, but he never talked about it. Another relative, who started a union, was accused of being un-American and blackballed.

These days, it almost seems quaint to make a list of taken-for-granted American traits back then: determination, the need for rigorous education, delayed gratification, and even stoicism. But Banks added something different and exciting for many of us.

Arriving in the big leagues just seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line, no sensible fan thought that Banks had come up easy. Hed even played in the Negro Leagues.

Everyone assumed that even if Banks temperament tended toward cheerfulness, there was something else at work. Ernie made himself want to play two, even on days when he undoubtedly didnt. And yet that habit of enthusiasm, that determination to focus on the love of the game for its own sake, seemed to become a reinforcing principle for him. The more he repeated it, lived it, the more it became true.

In short, maybe you could make yourself be happy.

All Banks fans will have their own affectionate version of Ernie. I imagine Banks on a hot August afternoon at Wrigley Field when the ivy vines are drooping and the Cubs flag in center field is near the bottom of the pole. He says, for the millionth time, Its a beautiful day for a ballgame. Lets play two.

Next page