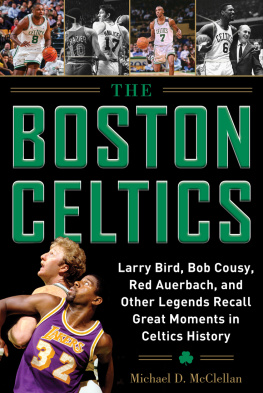

REBOUND!

BASKETBALL, BUSING, LARRY BIRD,

AND THE REBIRTH OF BOSTON

Michael Connelly

To the generation of school children who were sacrificed because adults

failed to find the middle ground between natural law and judicial law.

To my wife, Noreen, and son, Ryan, who are my blessing; my mom and dad, who guide me with the steady hand of love and support; my brothers and sisters, who arent just my siblings but my friends.

First published in 2008 by Voyageur Press, an imprint of MBI Publishing Company and the Quayside Publishing Group, 400 First Avenue N, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

Copyright 2008, 2010 by Michael Connelly

Hardcover edition published in 2008. Digital edition 2010.

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purposes of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or Publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

This publication has been prepared solely by MBI Publishing Company and is not approved or licensed by any other entity. We recognize that some words, model names, and designations mentioned herein are the property of the trademark holder. We use them for identification purposes only. This is not an official publication.

Voyageur Press titles are also available at discounts in bulk quantity for industrial or sales-promotional use. For details write to Special Sales Manager at MBI Publishing Company, 400 First Avenue N, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA.

Digital edition: 978-1-61673-147-2

Hardcover edition: 978-0-7603-3501-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Connelly, Michael (Michael P.)

Rebound! : basketball, busing, Larry Bird, and the rebirth of Boston / Michael Connelly.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-7603-3501-7

1. Boston Celtics (Basketball team)--History--20th century. 2. Basketball--Social aspects--Massachusetts--Boston. 3. Boston (Mass.)--Social conditions--20th century. 4. Boston (Mass.)--Race relations. I. Title.

GV885.52.B67C66 2008

796.323074461--dc22

2008023121

Editor: Josh Leventhal

Designer: Helena Shimizu

Printed in the United States of America

On the front cover, top: Red Auerbach and Larry Bird, June 8, 1979 (AP Images); bottom: School buses with police escort, South Boston, September 12, 1974 (photo Spencer Grant 1974)

Preface

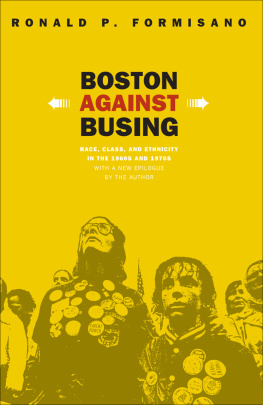

JUST BEFORE THE ORANGE LINE ARRIVED AT DUDLEY STATION, THE TRACKS BOWED OUT IN A PREGNANT CORNER OVER WASHINGTON STREET. When the subway negotiated this crooked bend, the wheels of the train screeched as if warning the passengers of impending danger. That noise made white riders sitting in seats or standing around poles clench their muscles, suffocate breaths, and avert eyes. On the stations platform awaiting the arrival of the train stood hard-working African Americans. They heard the same alarm and held the same fear and distrust. This was the world that Bostonians lived in during the days of forced busing, a time when tolerances became intolerant, where the line of demarcation was defined by race.

I grew up in a predominantly Irish-Catholic neighborhood of Boston called West Roxbury. It was inhabited mostly by firemen, policemen, and politicians of all sorts. My father, a probation officer, and my mother, an unemployed school teacher, found the means to send my five siblings and me to the safe confines of St. Theresa Elementary School for our education. At St. Theresa, we learned how to bless ourselves and say the Act of Contrition and play games of Relievio at recess and floor hockey in gym. The three Connelly boys were altar boys and played CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) sports; my three sisters learned to sew and spin a flag in the color guard. For the most part, the hostilities that existed just miles from our yellow colonial house on Perham Street were simply events that occurred on the nightly news, not much different than the conflicts taking place in Lebanon or Vietnam.

In the winter of 1978, I reached the ripe age of thirteen and immediately began the dance of independence with my parents. I was the fourth Connelly child to leap into the world of adolescence, and consequently my parents knew better than I how to play the game. Only after weighing risk and reward would they allow me to taste the fruits of freedom. On one such occasion, a tame Sunday afternoon in February, I was allowed to join my friends on a trip to the Boston Garden to watch the Boston Celtics play in a matinee game. In previous seasons, Celtic tickets were scarce and not available to aimless teenagers. Sadly, this edition of the men in green was a pathetic shadow of the glory years. Losses at the Garden, which used to be the exception, were now the norm. Players who wore the shamrock on their chest and squeaked high-top black sneakers around the parquet floor were more likely to be booed than cheered as shots and passes often went wayward from their intended destination. Names like Curtis Rowe, Sidney Wicks, and Marvin Barnes did little to rekindle warm memories of Sam Jones, Bob Cousy, and Bill Russell. The inadequacies on the court only served to further frustrate the fans, who came to the Garden to escape the turmoil that existed out on the streets of Boston.

On this Sunday, the futility of the home team couldnt spoil our fun. On our way home on the subway, we took turns exchanging stories along with the other Celtic fans on that train who laughed and told hearty accounts of the game. That was until the train stuttered, slowed, and then rolled toward the next station. Over the static-filled intercom, the conductor called out, Next stop, Dudley Station. Dudley Station everyone.

Instantly, a quiet swept throughout the car. Dudley Station was the stop on the Orange Line where confrontation between the races often occurred, as it marked a transition point between a black neighborhood and a white neighborhood. Jovial conversations turned to whispers, and cynical women gripped their handbags. My two friends and I paused in midsentence as we stood around a shared pole. When the train finally came to a halt, the doors to the platform parted left and right, allowing passengers to disembark. But before the departing riders had a chance to clear the doors, an unknown, long-haired, white teenager, who happened to be sharing our pole, yelled with all the anger of Boston in the 1970s, All niggers off!

Here we were in the midst of one of the most volatile racial storms in the history of Boston, and one side had just dared the other. White riders throughout the train melted in shame while departing black riders took home with them a reminder of hatred. All, that is, except for the very last black passenger who arrived at the doors. He came to a halt, preventing the sliding doors from closing. This delay annoyed the white teenager, who then advanced his challenge: That means you, too.

Pushed beyond the limits, the black man spun on his heels and, with a look of both fear and fury in his eyes, withdrew his hand from his coat pocket. In his hand, he held a handgun, which he pointed at a collage of white faces, not quite sure who had offered the ultimate insult.

At that moment, time froze. A man now held my life in the flex of his right index finger. Because he couldnt identify the author of the racist challenge, he shined the gun on all who stood in vicinity of the utterance. When it was my turn to have the gun set upon me, I could only hope that it was the intention of the gun bearer to send a message of defiance to the riders who would continue past Dudley Station to their houses in white neighborhoods. For this brief yet seemingly never-ending instant, our train had become the epicenter of the Boston racial conflict. Finally, the black man stepped backward off the train with the gun held out as if he were still pondering whether to fire his weapon. While he weighed his options, the doors of the car closed and the train rumbled down the tracks.