Contents

Guide

Page List

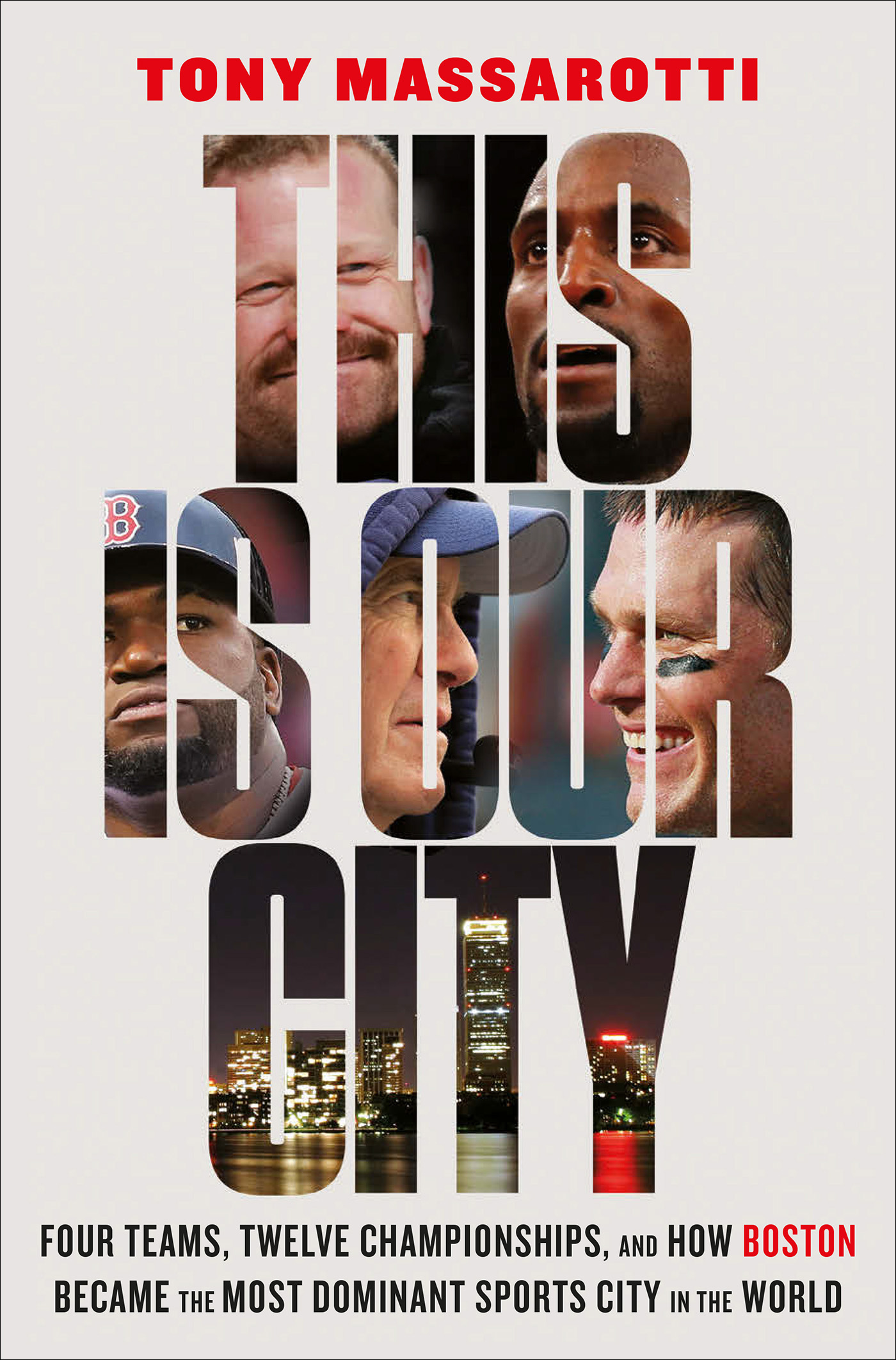

Also by Tony Massarotti

A Tale of Two Cities: The 2004 YankeesRed Sox Rivalry and the War for the Pennant (with John Harper)

Big Papi: My Story of Big Dreams and Big Hits (with David Ortiz)

Dynasty: The Inside Story of How the Red Sox Became a Baseball Powerhouse

Knuckler: My Life with Baseballs Most Confounding Pitch (with Tim Wakefield)

Copyright 2022 Tony Massarotti

Cover 2022 Abrams

Published in 2022 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022933717

ISBN: 978-1-4197-5358-9

eISBN: 978-1-64700-254-1

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

For Boston

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

To me, Boston always has felt like a neighborhood... Its one of the things I love most about playing there.... Ive invested in Boston during my time there, and I feel like Boston has invested in me.

longtime Boston Red Sox pitcher Tim Wakefield in his memoir, Knuckler: My Life with Baseballs Most Confounding Pitch

In the middle of it all, in the heart of Boston and amid a crisis that shook the city and the country to its heels, David Americo Ortiz spoke. He spoke for himself. He spoke for his teammates. And he spoke for fans, neighbors, public servants, and city officials during a time Boston boomed with pride, trembled with fear, celebrated its considerable history, and pondered its suddenly uncertain future.

These jerseys that were wearing today, it doesnt say Red Sox. It says Boston, Ortiz noted just beyond the first baseline at Fenway Park, Bostons kitchen, its core. We want to thank youMayor [Tom] Menino, Governor [Deval] Patrick, the whole police departmentfor the great job that they did this past week.

And then he said this:

This is our fucking cityand nobody is going to dictate our freedom.

David Ortiz raised his fist.

Stay strong, he said.

And then, as if both stunned by Ortizs unexpected vulgarity and in completely unabashed agreement, a capacity crowd at Fenway Park roared to a crescendo, nodding in approval, clapping furiously. Did Papi just say what I think he said? Indeed he did. Well, amen to that. Just five days after the Marathon bombings of April 15, 2013, which took three lives, wounded nearly three hundred people, and left sixteen others without limbs, Bostonians were also psychologically scarred, significantly wounded. They were unsure. They were frightened. They were also mad as hell and looking for somethingor, perhaps, someoneto rally around, and they found him in Ortiz, nicknamed Big Papi, the titanic teddy bear around whom the Red Sox had been built for the better part of the twenty-first century.

In all, Ortiz addressed Bostonians for less than forty seconds on that brilliant sun-splashed afternoon of Saturday, April 20, 2013, though his words continue to resonate as if he had delivered the Gettysburg Address. At the start of what would become yet another championship during Bostons dynastic beginning to the new millennium, Ortiz was as qualified as anyonemore so, reallyto lead Boston back from tragedy, to preach unity and resolve, to commence the healing. As the designated hitter of the Red Sox, Ortiz was a giant, someone more identifiable to Americans than the mayor or the governor. Born under the red, white, and blue flag of the Dominican Republic, Ortiz had come to Boston from the Minnesota Twins and resurrected his baseball career, put an end to the mythical Curse of the Bambino, and led Boston to two championships (and had the Red Sox on the way to a third).

In the process, Boston had become his home. By 2013, Ortiz was in his eleventh season of a Red Sox career during which he had initially struggled for a foothold, eventually endured, and ultimately succeeded. Boston has never been the kind of place to storm in and sweep people off their feet, after all, and the list of those rejectedparticularly athleteswas long and distinguished.

Who are you? Where are you from? What do you want here?

But now? Ortiz was not merely welcomed. He had the right to preach, to rage, to lead. His uniform alone spoke volumes. For home games at Fenway Park, the Red Sox customarily wore their traditional white jerseys and pants trimmed in red piping, with button-up tops, black leather belts, red numbers and letters outlined in blue, the words RED SOX emblazoned on their chests in a familiar, unique font. But on April 20, 2013, as Ortiz succinctly pointed out, the jerseys this time featured BOSTON in all-red letters, with no piping and no trim, an understated style designed to issue the simplest of reminders: that the Red Sox were not merely representatives of their city and its values nor solely ambassadors for those from all six New England statesthey were neighbors and fellow taxpayers, too, shoulder to shoulder, arm in arm.

Our city.

This is our city.

This is our fucking city.

Beyond the acceptance by Bostonians, Ortiz was, of course, the perfect man to cross all barriers. He was bilingual, fiercely competitive, wonderfully engaging, genuinely good-hearted, talented and gritty, relentless but patient, and also imperfect. Along with New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady and coach Bill Belichick during the citys astonishing run of sports championships to start the millennium, Ortiz had become as synonymous with Boston as Paul Revere and the Old North Church. Brady and Belichick had won three championships by then, Ortiz two. The Celtics and Bruins had won one each. Boston had become, in the arena, the Athens or Rome of American sports, the center of the sports universe, the Hub. Boston had defeated Los Angeles. Boston had defeated New York. Boston had defeated Philadelphia and Boston had defeated St. Louis. The Boston Marathon bombings were something altogether different, of course, but Boston believed in David Ortiz. Boston trusted him.

And if Boston believed in him, the country did, too. Nearly twelve years after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Boston had become the primary target this time, the victim. When Ortiz spoke on this occasion, all of America was listening.

You get goose bumps [listening to the speech], Boston mayor Marty Walsh would say years later. At that point, Mayor Tom Menino was sick and we were all in a state of shock, fearand Big Papi made a statement about our city. He basically put a stake in the ground, and that helped in the healing process. He was speaking for a lot of people. I dont advocate that athletes use that language, but he certainly drove his point home.

Said Tom Manchester, vice president of field marketing for Dunkin Donuts, the Boston-based coffee empire for whom Ortiz was a spokesperson: For me personally when he gave that speech, he could have dropped the F-bomb 10 times and it really wouldnt have mattered to me because I was feeling that way and I think he articulated what all of New England was feeling.