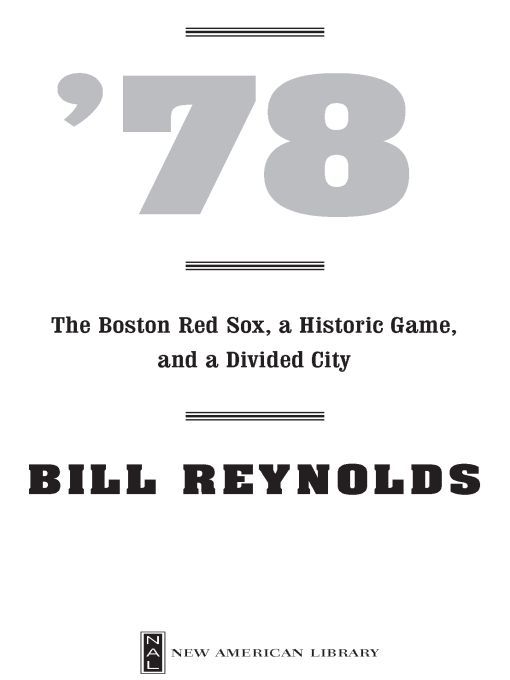

Table of Contents

To my sister, Polly Reynolds,

whose spirit in the midst of daily adversity,

is a constant inspiration.

And to Lizzy, for her ongoing support

and encouragement.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A special thank-you to:

David Vigliano, my agent and professional adviser for twenty years now, who saw that this could be a book when it was just an idea floating around in my head.

Dan Ambrosio, who shepherded the idea through the world of New York publishing.

Mark Chait, who edited this book, shared the same vision of it that I had, and made it better at the crucial time when it needed it most. No writer can ask for more.

Art Martone, the sports editor at the Providence Journal, whose insight into the Red Sox in the seventies was instrumental in the beginning of the process.

The Red Sox, specifically Dick Bresciani and Pam Ganley, who went out of their way to be helpful.

Liz Abbott, whose help in research and in acquiring the pictures was invaluable.

Isabelle Brogna, my techie wizard, who saved me from falling into a technological swamp, and Katie Myers, who helped with the pictures.

On September 25, 1978, the Boston Globes Ray Fitzgerald wrote a column on the sports page titled Lunacy and the Red Sox Fan.

Its premise was that an unidentified man had been found walking aimlessly on a Back Bay street, talking to lampposts and trying to interest a wire-haired terrier in a game of cribbage. So he was brought into a clinic and placed on a cot, a tag around his neck.

The doctor read the inscription on his tag.

I am a Boston Red Sox fan and no longer responsible for my actions. If found, bury me at home plate, next to the teams pennant chances.

The doctor shook his head.

Another one of those. Its close to an epidemic.

Yes it was.

And the Red Soxs collapse wasnt supposed to have happened, of course.

They were just three years removed from losing in the seventh game of the 75 World Series. They were a talented, tested team in its prime, with the iconic Carl Yastrzemski and Carlton Fisk, the regal catcher who seemed as solid as the New Hampshire of his youth. They had the strong-armed Dwight Evans in right field, the sure-handed Rick Burleson at shortstop, and the graceful Freddie Lynn in center, who had swept across that 75 season like a supernova in his rookie year. They had George Scott, the old Boomer himself, one of the last holdovers from the Impossible Dream team of 1967, one of the first black stars with the Red Sox, now trying to hang on, no longer able to pull the ball, his best days all in the past. They had Jim Rice, in the middle of what would turn out to be an MVP season, the most feared slugger in the game.

They also had quality starting pitching, no insignificant thing for the Red Sox, whose history always seemed to be a lineup that looked at the friendly left-field wall as a siren song but whose pitching forever seemed to betray them, my kingdom for an ace. Now they had four of them: the crafty Luis Tiant, with his trademark cigars in the locker room and a pitching motion that seemed like the baseball version of some guy running a three-card monte game on a street corner, now you see it, now you dont, complete with turning his back to the batter in the middle of his windup; the flamethrowing Dennis Eckersley, who always looked as if he were on his way to Studio 54 in New York with his long hair, mustache, and chiseled features, and had his own language to match, a combination of California slacker and surfer dude; Mike Torrez, who had been with the Yankees the year before but was now with the Red Sox, this gun for hire; and the irrepressible Bill Lee, the Spaceman himself, baseballs counterculture hero whom Eckersley called Sherwin Williams because he was a master at painting the corners of the plate.

The same Bill Lee who had said three years earlier that the only person in Boston with any guts was Judge W. Arthur Garrity, the man who had ordered the forced busing that had torn the city apart.

In the middle of July they had an amazing fourteen-game lead on the Yankees and were eight ahead of the Milwaukee Brewers, and seemed to be on cruise control to win the division, especially since the Yankees were in a free fall, a dysfunction in pinstripes, a melodrama masquerading as a baseball team. It was as if this was the Red Sox team all of New England had been waiting for ever since 1918, the last year the Red Sox had won a World Series. They were the best team in baseball. The record said so.

Then the swoon had started.

There had been a combination of reasons, certainly, everything from injuries to the theory that manager Don Zimmer played his regulars too much, and thus burned them out, to the vagaries of the game itself. All this had combined with the Yankees starting to play appreciably better after manager Billy Martin suddenly resigned in another installment of the miniseries that had become the Yankees, and was replaced by Bob Lemon, a move that quieted the chaos and began to bring the curtain down on all the drama.

In early September the Yankees came into Boston for a four-game series in Fenway Park, and by this time they were only down four, so close now the Red Sox could hear their breathing. When they left Boston the two teams were tied, and the Yankees had outscored them 42-9 over the four games, four games in which the Sox seemed as gone as summer, as if all their flaws were outlined in neon.

This is the first time Ive seen a first-place team chasing a second-place team, said Tony Kubek, the former Yankee shortstop, on NBC.

The Yankees reliever Sparky Lyle, who was infamous for sitting naked on cakes that had been delivered to the Yankee clubhouse, then asking his teammates, Do you want a piece? would later say that the Sox had been so bad he pitied them.

The Yankees felt that the Red Sox had worn the pressure on their faces all that weekend, and each loss had seemed to take a little more of the spirit out of them. The Sox swoon resurrected all the tortured history. How they hadnt won a World Series since 1918. How they had lost two World Series seventh games in the past eleven years. How they seemed almost cursed, forever unable to win the big one, the sense that the Red Sox truly were New Englands team, with their gloomy Puritan forefathers and their sermons on sin, with the foreboding that now seemed to hover over the franchise like some angry old ghost. As if their history was something they couldnt shake, even as the decades came and went, and the players came and went, and everything changed, except for the fact that the Red Sox never won it all.

Fenway Park was like St. Petersburg in the last days of Czar Nicholas, Peter Gammons wrote in the next weeks Sports Illustrated under a headline that read The BOSTON MASSACRE.

This was the team that had been so good the first half of the season?

This was the team that had been called the best team in Red Sox history?

This was the team that at one point had led the Yankees by fourteen games, causing the Yankees Reggie Jackson to quip, Not even Affirmed can catch them, a reference to the great horse who had won the Triple Crown that year.

But the Yankees had caught them. They were tied in the standings and the Red Sox seemed as gone as weekends at the Cape. They also seemed to be limping toward the finish line like some old horse longing for the barn. Yastrzemski was in and out of the lineup with an assortment of minor injuries. Fisk had been playing with a cracked rib. Butch Hobson, the young third baseman with his native Alabama running through his speech, had bone chips in his right elbow that made it painful to throw across the infield, the main reason why he led the major leagues in errors. Lynn had bad ankles. Burleson had an ankle problem. Evans had been beaned in late August and still had dizzy spells.