Table of Contents

To my brother, Geoffrey

PROLOGUE

In the spring of 2008, the Celtics were in the NBA Finals, trying to put a seventeenth banner up in the rafters of the TD Banknorth Garden in Boston.

The Drive for 17.

That had been the slogan that spring, the catchy phrase, as once again Boston and all of New England were caught up in another Celtics play-off run.

It had been twenty-two years since the last one, back when the names had been Larry Bird and Kevin McHale, DJ and Danny Ainge, back when the Celtics in the NBA Finals seemed all but built into the schedule, a rite of spring. It had been more than two decades of the NBA Finals being held in other cities, and during that period the Celtics seemed to drift farther and farther into irrelevancy, overshadowed by both the Red Sox and the Patriots. It was as if their glory days were all in the past tense, those sixteen championship banners up in the rafters, once a symbol of excellence, beginning to stare down like accusers.

The spring of 2008 changed that.

Not only did it resurrect interest in the Celtics; it also resurrected interest in the Celtics storied history, the one represented by all those banners, the constant reminder of what the Celtics had once been. And as the Celtics got closer and closer to that seventeenth title, the Garden became loud and alive again. The hope was for another great Celtics team for a new generation, with Bird, McHale, and Parish morphing into another Big Three of Kevin Garnett, Paul Pierce, and Ray Allen. You could almost close your eyes and see it as all the same story, one big continuum, one banner no different from another.

But what did they know?

That was the question I asked myself as people flocked to this new Garden, with its earsplitting music and light shows, flashing message boards, and bump-and-grind dancers; such were the accoutrements of todays NBA.

What did they know of that first banner, the one from 1957, the one that had started it all?

For you had to be over age sixty to remember it; you had to have grown up with Ike in the White House and Elvis all over the radio. You had to have come of age in the era of fallout shelters and Sadie Hawkins dances in the gym, back before the Beatles and the Kennedys, before Vietnam and color television, back when social unrest was some kid hot-rodding his car in some quiet suburban neighborhood. You had to have grown up in such a different America, a time when the civil rights movement was still in the future and there were few African-American players in the NBA. It was such a different basketball world.

Even then, you might have been a little late to the dance, too young to remember the early days of the NBA, back when professional basketball had all the glamour of roller derby. Often called a goons game, it was frequently ignored by both the big-name newspaper columnists, who didnt consider it worth their attention, and by the majority of the American sporting public. The NBA was in only its eleventh year in the spring of 57, that spring that started the Celtics story.

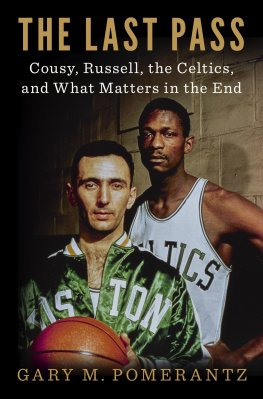

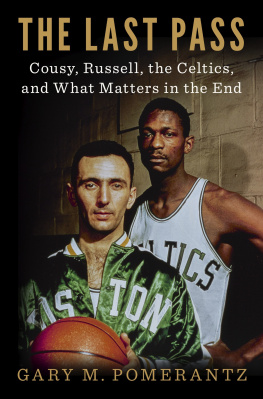

To many in the new Garden in the spring of 2008, the NBA had started with Larry Bird and Magic Johnson in the late seventies. This was often the historical reference point, the beginning of the modern NBA story. Certainly it was the renewal of the great Celtics-Lakers rivalry. Or else it was Michael Jordan a few years later, the beginning of the glittering world of megasalaries, huge endorsements, and stars who walked across the American sports landscape like young princes. To many in the Garden that spring, what they knew about those first years of the Celtics dynasty, of names like Cousy and Russell, they knew from grainy old news-reels and black-and-white photographs, those remnants of another era. Or they knew them from the message board in the Garden, where the icons of history were periodically flashed up when the Celtics paid homage to their past.

Occasionally, they would still be at the Garden, a visible presence, living history. Cousy had been an analyst on the Celtics television games for years. You couldnt be a Celtics fan without knowing who Bob Cousy was, even if the only time you had seen him play was on an old newsreel; even if you didnt know that once upon a time hed been called Mr. Basketball, back in the mid-fifties when he was arguably the biggest name in the game, the flashy guard who threw the ball behind his back and did things on a basketball court that few people had ever done before, one of the players who had made the NBA respectable in an era when so many people in American sport thought it wasnt.

The same was true for Bill Russell, of course, the other mythic figure of the Celtics.

He had been the long-lost Celtic, now back after being away for so long. His time as a Celtic always had been complicated, all the winning and all the titles marred by the prejudice and the discrimination he always had felt in Boston. He was undergoing a certain rebirth, now being called the greatest winner in the history of American sport. There also was the sense, rightly or wrongly, that he had somehow softened, as if most of his battles already had been fought, his demons exorcised. Now he waved to people, laughed his big cackle of a laugh, and to those who had known him in the past, it all seemed incongruous, as though he simply had to be the friendlier twin.

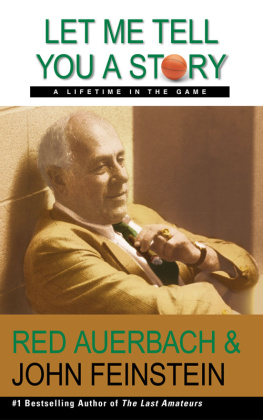

The fans in the Garden had always known Arnold Red Auerbach, who passed away in 2006. Hed been a presence at many Celtics game, the old patriarch walking with a cane in those twilight years, always sitting near midcourt across from the benches, about ten rows up. He was regarded as one of the greatest coaches in basketball history, complete with his nine NBA titles to prove it. More important, he was the one constant in the Celtics long history, as the players came and went, as the eras changed. He had morphed from coach, to general manager, to president, but those were just titles. He was the Celtics, a Boston institution right up there with Paul Revere and Fenway Park, Ted Williams and the Kennedys, complete with the statue at Faneuil Hall to prove it.

The Celtics tradition?

In the end, it was Auerbach.

And through the years, as his legend grew and all those championship banners in the rafters kept staring down at fans, his mystique grew, too. The Celtics are down? Red will think of something. The Celtics need a power forward? Dont worry, Red will bamboozle some general manager somewhere. As if regardless of who the Celtics coach was, or what the names on the door said, Red was really the guy pulling all the strings behind the big curtain; Red was the true wizard.

That had been the perception, and it had remained so until the late nineties, when Rick Pitino became the basketball boss of the Celtics and it became apparent that Auerbach officially was retired, his duties only ceremonial.

By then, Auerbach had long ago become mythic, the fact and the fiction having been sprinkled together for so long, it almost didnt matter what was true and what wasnt. He was revered in ways that would have been unimaginable for many of the sportswriters who had known him when he first came to Boston in 1950. He was revered in ways that would have been unthinkable back in the fifties, back when hed been trying to carve out a reputation for himself, back when it hadnt always been easy.