Copyright 2018 by Gary M. Pomerantz

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

In the next life, Ill do email and Ill be able to dunk.

PREFACE: APRIL 9, 1957

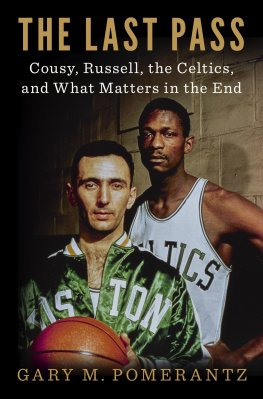

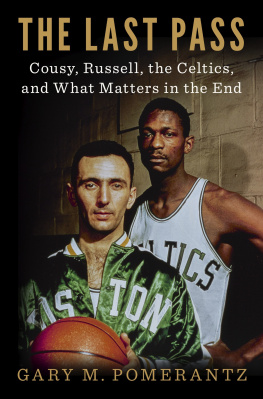

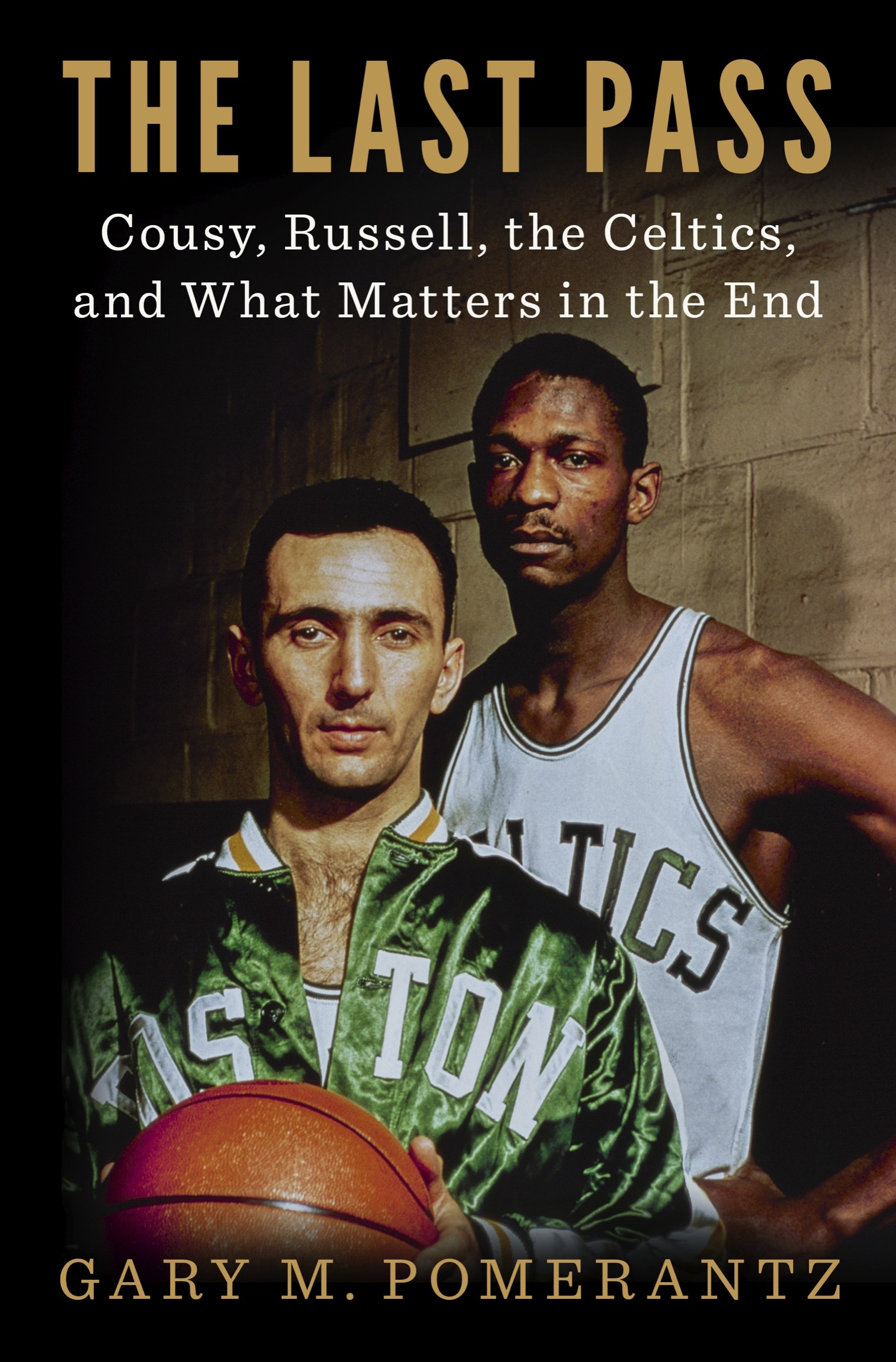

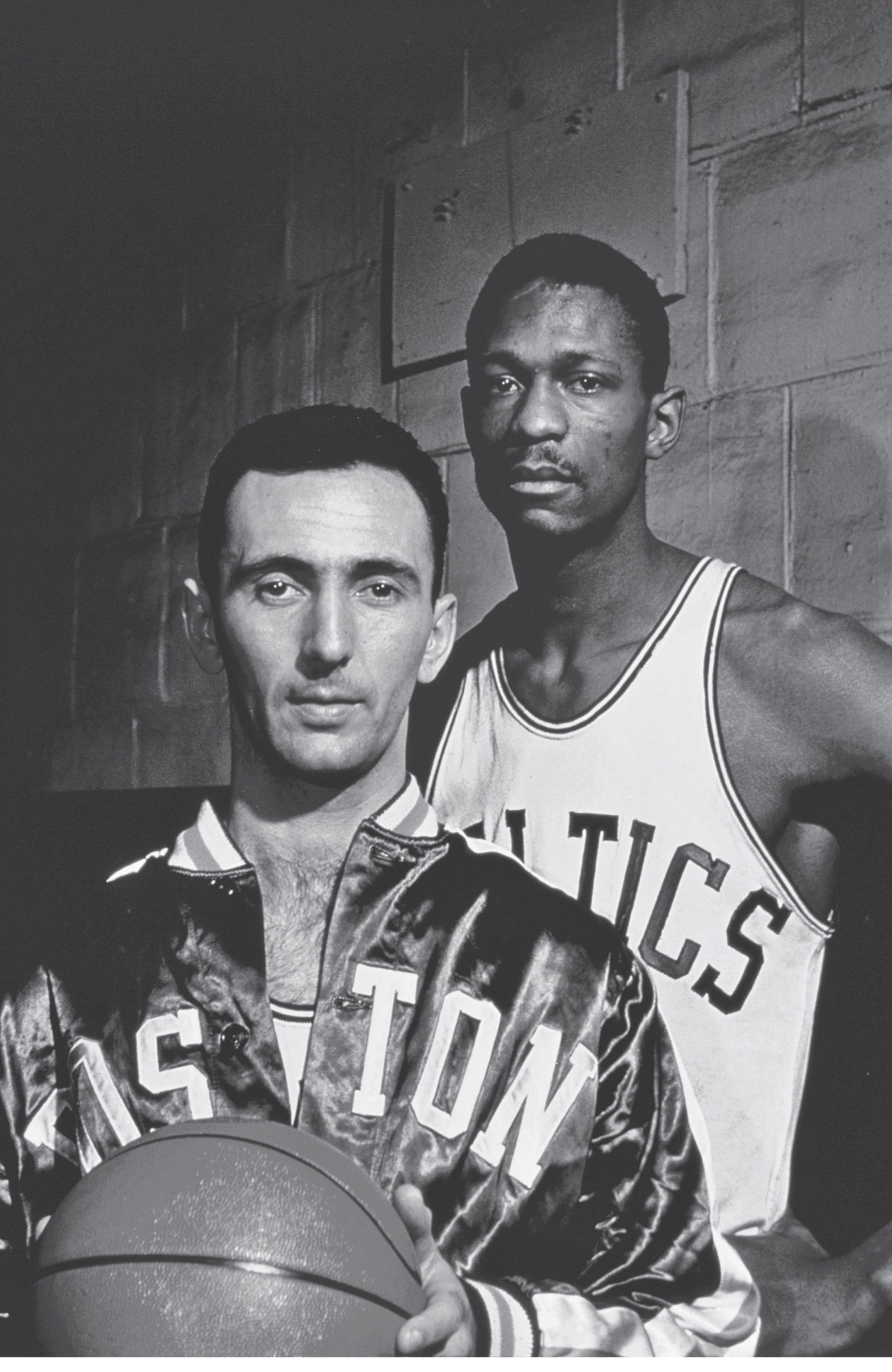

Study the portrait closely. It captures the moment the greatest American professional sports dynasty of the twentieth century took flight. The dynasty was born of a merger of two men more alike than they ever understood. Both outsiders, they were self-analytical and murderously competitive. They moved through separate worlds off the court, but on the creaky parquet floor of the Boston Garden they were interlocking pieces. They blended passing and shot blocking, dribbling and rebounding, offense and defense. They were white and black. They were Cooz and Russ.

At the moment the camera flashed, Bob Cousy was twenty-eight, Bill Russell twenty-three. Cousy, the captain, had been with the Boston Celtics for seven seasons; Russell, the rookie whose arrival was delayed by his participation in the Melbourne Olympics, for about a hundred days. They played in a time when sportswriters still created nicknames for star athletes as if they were comic-book superheroes. As Babe Ruth once was the Sultan of Swat and Joe Louis the Brown Bomber, Cousy was the Houdini of the Hardwood. Russell would become the winningest player in National Basketball Association history, but he escaped without a nickname. He was just Russ.

Richard Meek was the photographer. He shot forty-five covers for Sports Illustrated and Life. His camera caught Ali, Nixon, Bette Davis, Arthur Ashe, James Cagney. In the tunnel outside the locker room at the Boston Garden before Game 5 of the 1957 NBA Finals between the Celtics and the St. Louis Hawks, Meek used two portrait lights. As Cousy and Russell stood in front of a cinder-block wall, the brilliant lights gave their eyes a celestial spark. In 1928, the arenas creator, boxing promoter Tex Rickard, settled for the industrial ambience of a cramped workingmans arena perched above the cacophony of North Station across Causeway Street. More than once, Cousy declared that the Gardens rats were bigger than the customers.

The photographer may have reached for symbolism in his positioning of the Celtics: Cousy up front, bathed in satiny warmth, and Russell in the back, partially concealed and in shadow. Certainly, that was how white sportswriters at the Boston dailiesand they were all whiterepresented the two players in the sports pages, as if to say, This is Coozs team and Coozs town. Still, Meeks photograph suggested another truth. Even as Cousy won the leagues Most Valuable Player award in 1957, the rookie Russell loomed. Already he had begun to take over.

They posed for Meek minutes before tip-off. Their minds were elsewhere, on the battle against the Hawks Bob Pettit, the Bombardier from Baton Rouge. Their expressions are taut, severe. They might have been Civil War soldiers standing for Mathew Brady. The rookie Russell offers a hint of the menacing glower that, years later, he would describe as a big batch of smoldering Black Panther, a touch of Lord High Executioner and angry Cyclops mixed together, with just a dash of the old Sonny Liston. On first glance, Cousy seems made of porcelain, smooth and soft. But his eyes are fixed in a hard stare.

A Boston sportswriter, Bill McSweeny, had seen those faces before big games. He had entered the Celtics locker room worried and left reassured by the sight of Cousy alongside Russell. The Celtics coach, Red Auerbach, didnt much worry. He once broke an uncommon tension in the locker room by barking out, Hey, if you guys are worrying about playing them, how do you think they must feel having to play us? The Celtics laughed, knowing he was right.

Meek snapped this portrait four months after the successful conclusion to the Montgomery Bus Boycott started by Rosa Parks. In another five months, the Little Rock school desegregation crisis would prompt President Eisenhower to send federal troops. Cousy and Russell played in Boston, birthplace of the American Revolution, the abolitionists, the Kennedys, and all those colleges and universities, including Boston University, which had awarded Martin Luther King Jr. his doctorate only two years before. But there was another side to Boston. Court-ordered busing in the seventies would peel away the veneer and expose Bostons deep racial fissures for all to see, but they were always there. Still, in these years of growing racial unrest, the two Celtics stars, a white man and a black man, merged their ambitions, skill sets, and sweat for a shared success built on a foundation of mutual respect.

Hours after Meek took this portrait, Cousy, Russell, and the Celtics defeated St. Louis in Game 5. Four days later, they won their first title. If anyone called it the NBA championship, Auerbach would wag his finger and correct them: It was the worlds championship.

Then the Celtics won it again, and again, and again, and...

It all began with the ball in Houdinis hands.

Sixty years later, as an old man, Cousy studies the same portrait. He says those two guys might have come from the wake of a dear friend. Then, upon deeper study: It really looks like we are on a death march. But he knew better. He knew what the camera caught: the ultimate game face.

Mostly there is solitude now on Salisbury Street in Worcester, Massachusetts, near Boston, where Cousy, just months from his ninetieth birthday, walks with a cane, reads voraciously, and lives alone with echoes and memories in the sprawling 6,300-square-foot house that he and his wife, Missie, bought in the final months of the Kennedy administration. Missie died in 2013they were married nearly sixty-three yearsbut her spirit fills the house. The painting of her wearing her good-luck green dress, a gift from the New York Knicks on Bob Cousy Day in 1963, hangs in the dining room. As part of his daily protocol, Cousy begins each morning by walking to his bedroom bureau and addressing Missies funeral Mass card. Gmornin, sweetheart, he says. I love you!

The men who were the Celtics were more prolific over a thirteen-year span than the New York Yankees, Green Bay Packers, and Montreal Canadiens ever were, winning eleven NBA championships from 1957 to 1969, including eight consecutively. That dynasty began with Cousy. He played thirteen pro seasons for the Celtics, made thirteen all-star teams, won six NBA championships, captured that 1957 Most Valuable Player award, led the league in assists eight times, and averaged 18.4 points per game. It wasnt only what he did but