Table of Contents

TO MAX

MY LOVE AND MY LIFE

CHAPTER 1

NEVER ENOUGH

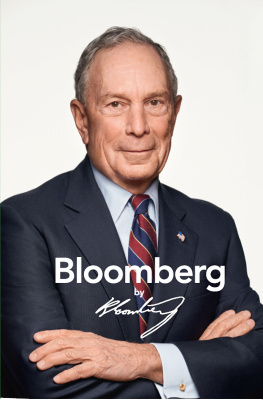

THE FIRST TIME I met Mike Bloomberg was in the late 1990s at a dinner party in his Manhattan town house. It was a typical New York gathering of the moneyed and the prominent, thrown together for an evening of polite conversation that goes in one ear and out the other.

I recall that Dan Rather was there, and Peter Jennings, and that the five-story home was an overdone tribute to marble, formal British furniture and attention-grabbing works of art.

Bloomberg himself barely made an impression. He sat at the head of the table and said little, looking bored. Later, as rumors grew that he wanted to run for mayor, I was astonishedand I was not the only one. That guy, the dull, quiet one whose home looks like a museum?

Id seen mayors come and go and Bloomberg did not fit the mold any which way. The slight, self-made billionaire was the opposite of the boisterous characters New Yorkers enjoy. He had created an improbably successful company, a financial information giant that grew from a sophisticated computer terminal he developed. Few beyond Wall Street and the City of London understood much about that or knew that Bloomberg was a generous philanthropist, but the elaborate ad campaign he could bankroll would fill in the blanks. Recognition wasnt the problem.The problem was, it sure seemed, Mike Bloomberg.

He didnt have the experience or the temperament, he didnt know much about the city, and the city knew less about him. Success in business was supposed to make him a good mayor?

He was trying to buy City Hall like its a cup of coffee, growled Jimmy Breslin. He was spending tens of millions of dollars of his own money to lip-sync the lyrics of politics, wrote Bob Herbert. By my reckoning, he was a rich guy on an ego trip, who should not have gotten anywhere near City Hall, no matter how many millions of his own dollars he spent in pursuit of victory.

After he won in a fluke, many New Yorkers remained skeptical, figuring he would be a caretaker mayor, serving one four-year term and moving on out. New York is hard enough for a seasoned politician to run, let alone a billionaire stiff. Bloomberg was nothing like one of those naturally expansive rich men like Nelson Rockefeller or the open, good-humored Warren Buffet.

He couldnt make a speech, couldntor wouldntanswer a question persuasively and projected a solemnity that approached sourness. A small, graying man with a few too many slightly bucked teeth that discouraged broad smiles, he looked like the businessman he was in his uniforms of expensive dark suits and loafers.

He did not pretend to have patience for small talk or even a modicum of introspection. He did not feel your pain and would not admit to any of his own. Curt, profane, cranky and willful, Bloomberg said and did what he wanted, hated to admit error and was insistently private to the point of paranoia.

Even after his many well-compensated handlers burnished a vanity version of the Bloomberg story, selling it in campaign literature and ads that filled TV screens like electronic wallpaper, New Yorkers did not get to know Bloomberg the way they got to know his predecessors.

That never fully changed.Years into his mayoralty, otherwise well-informed people who learned I was writing his biography revealed a basic ignorance about him, asking whether he inherited his wealth, wondering how many times he was married, if he had any children anddespite nasal evidence to the contraryif he was a native New Yorker.

A public that dines out on stories about its political celebritiesabout Barack Obamas childhood, Bill Clintons appetites, Joe Bidens gaffeswas starved by Mike Bloomberg. Diffidence is not supposed to succeed with a public that wants politicians to feel its pain. Neither is aloof elitism.

Yet the diffident, elite Bloomberg would become one of the most effective mayors in the citys history, holding on to high approval ratings for an unusually long time in punishing New York, earning the publics respect if not its warmth.

It is the paradox of Michael Bloomberg that his great power and wealth were never matched by the power of his personality. But, most notably in his early, most difficult days as mayor, he succeeded anyway in a tough political environment, guiding the city through both bad economic times and good ones.

In more than thirty years of covering New York, I certainly had never encountered a leader like Bloomberg, the citys first, and no doubt last, prideful plutocrat.

Like all hugely successful people, he was lucky as well as smart. His mayoralty benefited greatly from the national prosperity that fueled the citys recovery from the terrorist attacks of 9/11. But more than timing worked for Bloomberg; Bloomberg worked for Bloomberg.

In his first term, he led the city out of recession, smoothly managing the citys finances and services, keeping the central promise of his self-financed campaign to steer clear of influence peddlers and favor-seekers.

Despite his bland persona, Bloomberg pursued bold projects full of political risk. He shook up the citys dysfunctional school system, tried to attack traffic gridlock, broadened a city ban on smoking, revived the public hospitals. He doggedly challenged dealers of illegal guns, kept crime rates down, and becalmed race relations despite aggressive police strategies that offended minority communities and civil libertarians.

And in every rundown corner of the city he aggressively cleared the way for renovation and real estate development, to the chagrin of serious city planners and devotees of city landmarks, to the delight of builders, construction unions and pragmatists who share his preference for imperfect development over neglect.

More than once, Bloombergs ambitions outran his political skills and led to highly visible defeats. He failed to lure the Olympics to New York or build a grand stadium in a dilapidated stretch of Manhattan. He lost a campaign to force private cars out of midtown, and while his overhaul of the city schools is in itself an achievement, whether it will produce a better-educated generation is a matter of protracted debate.

He let politics seduce him, indulging a Walter Mitty dream of running for president of the United States, and when that pursuit collapsed, he turned crudely political back home. Ignoring the advice of his staff and offending some of his warmest supporters, he reversed himself on a law he had supported and rammed the changed statute through the citys weak legislatureall so he could stay in office for a third term.

Redefining himself once again with his blatant political grab, he would write yet another chapter in the improbable life of Mike Bloomberg, a purely American story of drive and wealth, celebrity, self-discipline and restless ego.

By 2007, he was considered to be the richest man in New York, the founder and owner of a communications behemoth that plastered his name across the globe. He was one of the most generous philanthropists in the country. He owned many luxury homes, flew wherever and whenever he wanted in his own private jets, enjoyed the companionship of a handsome woman.

Notwithstanding his suddenly ruthless politicking, he remained unusually popular for an incumbent mayor. New Yorkers, a pragmatic people, tolerated his churlish manner and naked ambition for what they got in exchange: an honest, independent broker with common sense who seemed to think nothing was impossible. If he didnt mess it up, he could join the very small club of New York Citys best mayors.