Contents

Landmarks

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to:

My greatest teacher

&

most challenging student,

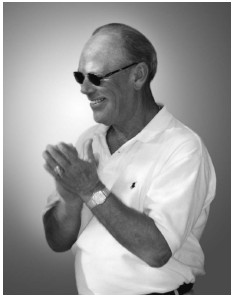

My father, Steve Gruwell

CHAPTER 1

W hy do we have to read books by dead white guys in tights? asked Sharaud, a foulmouthed sixteen-year-old, after he took one look at my syllabus.

Sharaud had entered my class at Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach, California, wearing a football jersey from Polytechnic High School. He must have known that donning the rival jersey was bound to get a rise out of the other students. He arrogantly strutted around my class, taunting the other players that he was going to take their places on the field, then leisurely strolled to the back of the classroom and took a seat.

As I started to discuss the curriculum, my students rocked in their seats and played percussion with their pencils. Some checked their pagers, while others reapplied their eyeliner. Some slouched, some laid their heads on the desks, and some actually took a nap. This was not the reception I was hoping for on my first day as a student teacher.

I dodged a paper airplanemade out of my syllabus, I quickly realizedand tried to make myself heard over a string of yo mama jokes.

I fidgeted with my pearls. I glanced at the polka-dot dress I was wearingit was similar to the one that Julia Roberts wore in Pretty Womanand wondered if I had chosen the wrong profession.

Why hadnt I gone to law school like Id originally planned? In a courtroom, unlike this chaotic classroom, a judge would bang his gavel with gusto after the first projectile had flown across the room, and any innuendo about his mothers integrity would bring instant charges of contempt of court. I needed a daunting authority figure in a black robe to tell these kids that they were out of order. I looked around the room, but an authority figure was nowhere to be found. Then came a panicked realizationI was the authority figure, armed only with a broken piece of chalk.

As a student teacher, I should have been able to rely on my supervising teacher, but he had stepped out of the classroom. When I met with him over the summer, he suggested that it would be a good idea for me to begin teaching on the first day of school, rather than easing my way into it. If you dive right in, he said, youll establish your authority from the get-go. From the comfort of his living room, this suggestion sounded great. I had visions of passing out my syllabus and having students stick out their hands like Oliver Twist and ask for more. In reality, the only person requesting more was my supervising teacher, who conveniently snuck out to get more coffee and never returned.

After nearly forty years of teaching, my supervising teacher planned to retire at the end of the school year. He had emotionally checked out and was now simply coasting on autopilot. Id assumed student teachers were to be handled like timid student drivers, with someone ready to grab the wheel when changing lanes or parallel parking went awry. Since my so-called mentor wasnt there to put on the brakes or take control, I didnt know which direction to go except forward.

To gain my composure, I tried to sound authoritative while reading my supervising teachers Guidelines for Student Behavior. I heard some students snickering. I stopped reading to see what they were laughing about.

You got chalk on your ass, yelled a student from the back.

Daaamn, girl! Can I have some fries with that shake? said another.

Somehow the Guidelines werent sticking, because the class was completely out of control. Even though I had studied classroom management, it was obvious that my students were the ones managing me. I just wanted to make it to the end of the hour.

Right before the bell rang, one of my students, Melvin, leaned back in his seat and announced, I give her five days!

Youre on, said Manny.

Im gonna make this lady cry in front of the whole class, Sharaud bragged as he walked out the door.

At that moment, I could hear my fathers smug I told you so echo in my mind. A little less foreboding than Beware the Ides of March, but accurate nevertheless.

I felt like a failure. It was obvious that I didnt know what I was doing. I had no idea how to engage these apathetic teenagers who hated reading, hated writing, and apparently hated me. And to make matters worse, student teachers did not receive salarieswe actually paid for the privilege! I was holding down two part-time jobs after school and on weekends to help pay for my semesters tuition at the university. I worked at Nordstrom department store as a salesclerk in the lingerie department and at a Marriott Hotel as a concierge. Paying to teach in the trenches was like putting my face through a cutout hole at a carnival while a quarterback threw pies at me. At least with a carnival, Id see it coming.

Once the students left, I picked up the paper airplane off the floor. I circled the room, collecting handouts that had been left behind, and saw ESL scribbled in black marker on several desks on the left side of the room. In educational jargon, ESL stands for English as a Second Language. Earlier, when Id seen ESL etched on my door, Id foolishly thought some Spanish-speaker was paying homage to my classroom. I soon realized this ESL had nothing to do with educationit was the acronym for East Side Longosthe largest Latino gang in Long Beach.

Similar gang insignias were on other desks. These defaced desks marked my students territory. The Asian students hit up the desks with the name of their respective gang affiliation, as did the African Americans. My multicultural classes in college had conveniently left out the chapter on gangs and turf warfare.

In lieu of a seating chart, I naively let the students pick their own seats. What struck me now was that they chose comfort zones determined by race. This realization gave me pause. I had imagined my students filing into my class and forming a melting pot of colors as they chose their seats, but the pot must have been pretty cold, because there was absolutely no melting. The Latinos had staked out the left side, while the Asian students occupied the right. The back row was occupied by all the African American students, and a couple of Caucasians sheepishly huddled together in the front.

My classroom wasnt the only place where the students segregated themselves. It was worse out on the school quad. During lunch, the students again separated themselves based on racial identity. The students even had nicknamed their distinct areas: Beverly Hills 90210, Chinatown (even though most of the students were immigrants from Cambodia), the Ghetto, and South of the Border.

The transparent segregation of the school shocked me, especially since I was expecting Wilson to be a model of integration. On paper, it was one of the most culturally diverse schools in the country, and Id chosen to student-teach at Wilson for exactly that reason. Clearly, there was a disparity between what Id read about Wilson High and its reality.

My dad used to share stories about seeing segregation firsthand. In the early sixties, when he was drafted to play minor league baseball for the Washington Senators, some of his teammates were forced to drink out of separate fountains, eat at different sections in restaurants, and stay at separate motels whenever his team traveled through the South. As a catcher, my dad said he judged a batter by his swing, not the color of his skin. So when Hank Aaron started hitting balls out of the park, my father hailed him as his new hero and named his daughter Erin in honor of the legendary batter.