THE FUNERAL

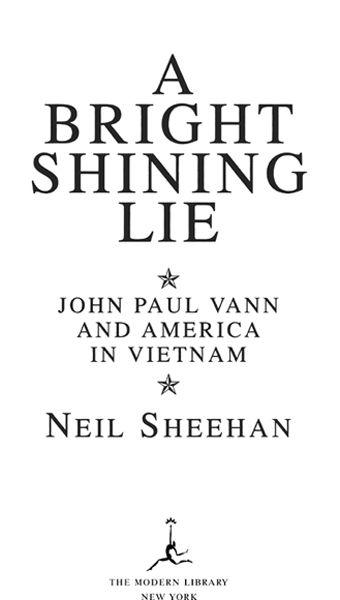

I T WAS a funeral to which they all came. They gathered in the red brick chapel beside the cemetery gate. Six gray horses were hitched to a caisson that would carry the coffin to the grave. A marching band was ready. An honor guard from the Armys oldest regiment, the regiment whose rolls reached back to the Revolution, was also formed in ranks before the white Georgian portico of the chapel. The soldiers were in full dress, dark blue trimmed with gold, the colors of the Union Army, which had safeguarded the integrity of the nation. The uniform was unsuited to the warmth and humidity of this Friday morning in the early summer of Washington, but this state funeral was worthy of the discomfort. John Paul Vann, the soldier of the war in Vietnam, was being buried at Arlington on June 16, 1972.

I T WAS a funeral to which they all came. They gathered in the red brick chapel beside the cemetery gate. Six gray horses were hitched to a caisson that would carry the coffin to the grave. A marching band was ready. An honor guard from the Armys oldest regiment, the regiment whose rolls reached back to the Revolution, was also formed in ranks before the white Georgian portico of the chapel. The soldiers were in full dress, dark blue trimmed with gold, the colors of the Union Army, which had safeguarded the integrity of the nation. The uniform was unsuited to the warmth and humidity of this Friday morning in the early summer of Washington, but this state funeral was worthy of the discomfort. John Paul Vann, the soldier of the war in Vietnam, was being buried at Arlington on June 16, 1972.

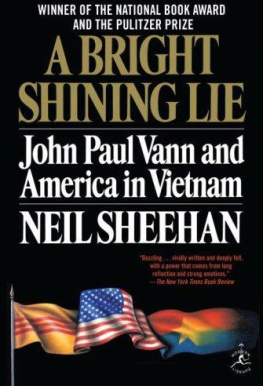

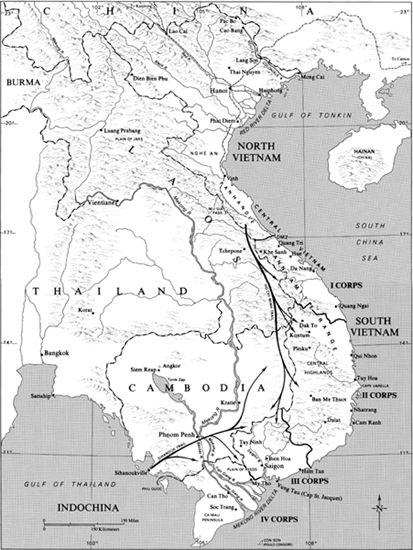

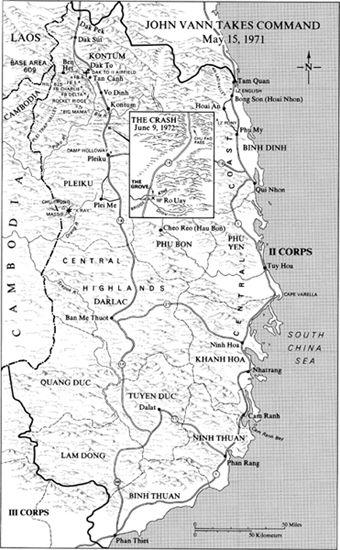

The war had already lasted longer than any other in the nations history and had divided America more than any conflict since the Civil War. In this war without heroes, this man had been the one compelling figure. The intensity and distinctiveness of his character and the courage and drama of his life had seemed to sum up so many of the qualities Americans admired in themselves as a people. By an obsession, by an unyielding dedication to the war, he had come to personify the American endeavor in Vietnam. He had exemplified it in his illusions, in his good intentions gone awry, in his pride, in his will to win. Where others had been defeated or discouraged over the years, or had become disenchanted and had turned against the war, he had been undeterred in his crusade to find a way to redeem the unredeemable, to lay hold of victory in this doomed enterprise. At the end of a decade of struggle to prevail, he had been killed one night a week earlier when his helicopter had crashed and burned in rain and fog in the mountains of South Vietnams Central Highlands. He had just beaten back, in a battle at a town called Kontum, an offensive by the North Vietnamese Army which had threatened to bring the Vietnam venture down in defeat.

Those who had assembled to see John Vann to his grave reflected the divisions and the wounds that the war had inflicted on American society. At the same time they had, almost every one, been touched by this man. Some had come because they had admired him and shared his cause even now; some because they had parted with him along the way, but still thought of him as a friend; some because they had been harmed by him, but cherished him for what he might have been. Although the war was to continue for nearly another three years with no dearth of dying in Vietnam, many at Arlington on that June morning in 1972 sensed that they were burying with John Vann the war and the decade of Vietnam. With Vann dead, the rest could be no more than a postscript.

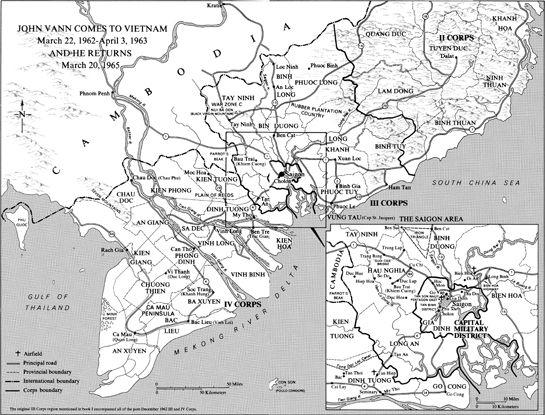

He had gone to Vietnam at the beginning of the decade, in March 1962, at the age of thirty-seven, as an Army lieutenant colonel, volunteering to serve as senior advisor to a South Vietnamese infantry division in the Mekong Delta south of Saigon. The war was still an adventure then. The previous December, President John F. Kennedy had committed the arms of the United States to the task of suppressing a Communist-led rebellion and preserving South Vietnam as a separate state governed by an American-sponsored regime in Saigon.

Vann was a natural leader of men in war. He was a child of the American South in the Great Depression, a redneck born and raised in a poor white working-class district of Norfolk, Virginia. He never tanned, his friends and subordinates joked during that first assignment in Vietnam. Whenever he exposed himself to the sun by marching with the South Vietnamese infantrymen on operations, which he did constantly, his ruddy neck and arms simply got redder.

At first glance he appeared a runty man. He stood five feet eight inches and weighed 150 pounds. An unusual physical stamina and an equally unusual assertiveness more than compensated for this shortness of stature. His constitution was extraordinary. It permitted him to turn each day into two days for an ordinary man. He required only four hours of sleep in normal times and could function effectively with two hours of sleep for extended periods. He could, and routinely did, put in two eight-hour working days in every twenty-four and still had half a working day in which to relax and amuse himself.

The assertiveness showed in the harsh, nasal tone of his voice and in the brisk, clipped way he had of enunciating his words. He always knew what he wanted to do and how he wanted to do it. He had a genius for solving the day-to-day problems that arise in the course of moving forward a complicated enterprise, particularly one as complicated as the art of making war. The genius lay in his pragmatic cast of mind and in his instinct for assessing the peculiar talents and motivations of other men and then turning those talents and motivations to his advantage. Detail fascinated him. He prized facts. He absorbed great quantities of them with ease and was always searching out more, confident that once he had discovered the facts of a problem, he could correctly analyze it and then apply the proper solution. His character and the education the Army had given him at service schools and civilian universities had combined to produce a mind that could be totally possessed by the immediate task and at the same time sufficiently detached to discern the root elements of the problem. He manifested the faith and the optimism of post-World War II America that any challenge could be overcome by will and by the disciplined application of intellect, technology, money, and, when necessary, armed force.

Vann had no physical fear. He made a habit of frequently spending the night at South Vietnamese militia outposts and survived a number of assaults against these little isolated forts of brick and sandbag blockhouses and mud walls, taking up a rifle to help the militiamen repel the attack. He drove roads that no one else would drive, to prove they could be driven, and in the process drove with slight injury through several ambushes. He landed his helicopter at district capitals and fortified camps in the midst of assaults to assist the defenders, ignoring the shelling and the antiaircraft machine guns, defying the enemy gunners to kill him. In the course of the decade he acquired a reputation for invulnerability. Time and again he took risks that killed other men and always survived. The odds, he said, did not apply to him.

I T WAS a funeral to which they all came. They gathered in the red brick chapel beside the cemetery gate. Six gray horses were hitched to a caisson that would carry the coffin to the grave. A marching band was ready. An honor guard from the Armys oldest regiment, the regiment whose rolls reached back to the Revolution, was also formed in ranks before the white Georgian portico of the chapel. The soldiers were in full dress, dark blue trimmed with gold, the colors of the Union Army, which had safeguarded the integrity of the nation. The uniform was unsuited to the warmth and humidity of this Friday morning in the early summer of Washington, but this state funeral was worthy of the discomfort. John Paul Vann, the soldier of the war in Vietnam, was being buried at Arlington on June 16, 1972.

I T WAS a funeral to which they all came. They gathered in the red brick chapel beside the cemetery gate. Six gray horses were hitched to a caisson that would carry the coffin to the grave. A marching band was ready. An honor guard from the Armys oldest regiment, the regiment whose rolls reached back to the Revolution, was also formed in ranks before the white Georgian portico of the chapel. The soldiers were in full dress, dark blue trimmed with gold, the colors of the Union Army, which had safeguarded the integrity of the nation. The uniform was unsuited to the warmth and humidity of this Friday morning in the early summer of Washington, but this state funeral was worthy of the discomfort. John Paul Vann, the soldier of the war in Vietnam, was being buried at Arlington on June 16, 1972.