For Mark and Janet

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away.... All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

Contents

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train...

THE FIRST EXPLOSIONS SEEMED VERY FAR AWAY...

A WAVE OF DIZZINESS CAME OVER HIM...

ONCE MORE HE RODE IN A WAGON...

THEY DROVE FOR WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN HOURS...

LOOKING OFF TOWARD THE BLANKNESS...

By David Horwich

Editors note: Speculative Fiction herein abbreviated as SF includes several types of genre literature, including science fiction and fantasy. Robert Silverberg, whose career spans half a century, is one of the foremost writers within this ber-genre. This interview was originally published in a slightly different form in Strange Horizons, www.strangehorizons.com, December 11, 2000.

Interviewer: Youve had an impressively prolific career as a writer. How do you maintain a high level of creativity and productivity? Do you have particularly disciplined working habits?

Robert Silverberg: Absolutely. When Im working, its Monday to Friday, week in and week out, at my desk at 8:30 and finished at noon, never any deviation. I work flat out all that time, no phone calls, no distractions. This is my schedule from November to April; I rarely work at all between April and November, but when I do, in some special instance, I maintain the same steady daily schedule until the job is done. Until 1971 I worked a longer day nine to noon, one to three and my output was accordingly greater, but after that year I saw no need to push myself quite that hard. But even now, when Im relatively inactive as a writer compared with my furious pace of decades ago, I feel no alternative but to keep to the steady schedule while Im working: I simply know no other comfortable way to work.

Interviewer: Have you ever run into writers block?

Robert Silverberg: There are plenty of days when Id rather not go to the office and write. I write anyway, on such days. Once I get started, the reluctance usually disappears.

In 1974, after years of prolonged overwork, I found that I simply didnt want to write any more at all. How much of this was due to changing reader tastes (the tilt toward comic-booky stuff like Perry Rhodan), how much to simple fatigue, how much to various upheavals that were going on in my non-writing life, I cant say. I hesitate to call it a writers block, because I define such blocks as the inability to write when the writer genuinely wants to write, and I simply didnt want to write anymore. After four and a half years, however, I felt I wanted to return to work and I sat down on November 1, 1978 and started Lord Valentines Castle without any difficulty at all, and continued on for the six months needed to write the book as though there had been no intermission at all.

I feel less and less like writing these days, but I dont think of that as writers block, either just as a desire to make life easier for myself as I get into my senior years. Whenever it seems easier on me to write than not to write I always have the option of writing something, which Ill be doing in a couple of weeks when I start a new novel, The Longest Way Home.

Interviewer: Youve written in a variety of genres what draws you to speculative fiction?

Robert Silverberg: It lit me up as a small boy and Ive wanted ever since to contribute important work to the genre that meant so much to me as I was growing up. Its more than light entertainment in my mind; it seems to me the thing I was put here to create, and though I have indeed done an inordinate lot of writing in many genres, Ive always felt I was dabbling, rather than really pursuing a career goal, when working at anything that wasnt speculative fiction.

One exception was the archaeological writing I did [e.g., Akhnaten: The Rebel Pharaoh, 1964]. Archaeology seeming to me the reverse side of the coin from SF exploration into the mysterious past instead of the unknowable future. And Ive crossbred a lot of my archaeological work with my SF [e.g., The Gate of Worlds, an alternative-history novel, published in 1967 and set in the 1980s, in which the civilizations of the Aztecs and the Incas are among the dominant world powers].

Interviewer: Which writers have had the greatest influence on you?

Robert Silverberg: Within SF, Jack Vance, Philip K. Dick, Robert Sheckley, Henry Kuttner, C.M. Kornbluth, Robert Heinlein. Plus others, but those are the obvious names. Outside SF, Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene come first to mind.

Interviewer: How does the process of collaboration compare to writing solo?

Robert Silverberg: I really havent collaborated that much. When I was just starting out I did a multitude of stories with Randall Garrett, who was living next door to me. His skills complemented mine. He was good at plotting and had an extensive scientific education, but couldnt stay sober long enough to get much work finished. I had greater insight into character and command of style, and better writing discipline, but lacked his scientific knowledge. We worked together for a couple of years, 1955-57, and then never again. My subsequent work has been virtually all solo except for a couple of stories I wrote with Harlan Ellison as a lark, and the three Asimov-Silverberg novels, in which I did nearly all of the writing because of the deteriorating state of Isaacs health. I dont particularly like collaborating and am not likely to do any again.

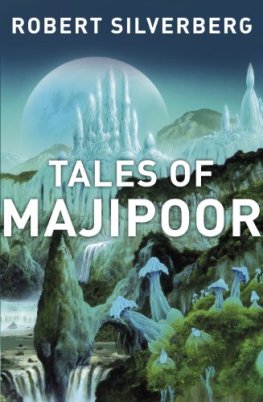

Interviewer: The Majipoor Cycle represents a different direction in your work an ongoing series that explores one enormous world, in contrast to the tightly constructed novels and stories that characterize much of your speculative fiction. Did you plan to write a continuing series, or did it grow in the telling?

Robert Silverberg: Originally I intended to write only Lord Valentines Castle, though I was aware that I had ended it with the question of Shapeshifter unrest unresolved. A year or two later I began writing the stories that made up Majipoor Chronicles to deal with various bits of Majipoor history that I thought were worth exploring, because it bothered me that there had been no occasion to deal with them in the original novel, and then, finally, I decided to do the actual sequel to Castle, Valentine Pontifex, to handle in a realistic way the questions I had raised in the first book.

As the series became popular I felt the temptation to return to Majipoor, and, since there was material in one of the Chronicles stories that seemed to call out for examination in detail, I conceived the idea of the second trilogy, which in fact takes place a thousand years before Castle.

Interviewer: The story of Gilgamesh appears in a number of your works. What special significance does this tale have for you?

Robert Silverberg: Its the oldest known story we have, and it deals with the most profound of issues the reality of death as well as the question of the responsibilities of kings. These are matters Ive often wrestled with and the figure of Gilgamesh neatly encapsulates them in metaphorical mode.

Interviewer: The novella Gilgamesh in the Outback

Next page