The Construction of Testimony

The Construction of Testimony

Claude Lanzmanns Shoah and Its Outtakes

Edited by Erin McGlothlin, Brad Prager, and Markus Zisselsberger

Wayne State University Press

Detroit

Contemporary Approaches to Film and Media Series

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu.

General Editor

Barry Keith Grant

Brock University

Southern Illinois University

2020 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4734-8 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-8143-4733-1 (hardback); ISBN 978-0-8143-4735-5 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019956854

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

Contents

Erin McGlothlin and Brad Prager

Lindsay Zarwell and Leslie Swift

Sue Vice

Jennifer Cazenave

Noah Shenker

Dorota Glowacka

Gary Weissman

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann

Erin McGlothlin

Brad Prager

Debarati Sanyal

Markus Zisselsberger

Leah Wolfson

Regina Longo

Compiled by Lindsay Zarwell and Jennifer Cazenave

Most of the contributions in this volume originated as papers presented at a workshop on Claude Lanzmanns Shoah outtakes, which was held at the University of Missouri in November 2015. The editors are grateful to the Research Council of the University of Missouri and the Washington University Center for the Humanities for providing the financial support that made that workshop possible. At the University of Missouri, Robert Greene and Stacey Woelfel helped secure additional funding. We would like to thank Rmy Besson, Sven Kramer, and Michael Renov for their participation in and feedback at the workshop. Further, we are grateful to Heidi Grek of Washington University in St. Louis for assistance in assembling this volumes bibliography.

From the very first stages of this project, we have been able to count on Lindsay Zarwell and Leslie Swift at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museums Spielberg Film and Video Archive. Without their expert guidance, this project would never have come to fruition.

Finally, Wayne State University Press has been extremely supportive throughout the many stages of publication. We are grateful to Daniel Magilow and an anonymous reviewer, who provided extremely helpful feedback. We are also particularly indebted to our acquisitions editor, Marie Sweetman, to the series editor, Barry Keith Grant, as well as to Kristin Harpster and Emily Shelton, all of whom kept everything moving forward.

Inventing According to the Truth: The Long Arc of Lanzmanns Shoah

Erin McGlothlin and Brad Prager

In 2016 Lindsay Zarwell, one of the lead archivists at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museums Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive, which is associated with the USHMMs project to restore and digitize the many hours of outtakes from Claude Lanzmanns epic Holocaust documentary Shoah (1985), drew our attention to a historically compelling and visually unorthodox interview that Lanzmann chose not to edit for inclusion in the final theatrical release of his film. The Ziering Oppenheimer interview is a nearly two-hour discussion with Herman Kempinsky (who later changed his name to Hermann Ziering) and Lore Oppenheimer. At the time of their meeting with Lanzmann, the two were copresidents of the Society of the Survivors of the Riga Ghetto.

In many ways, Lanzmanns joint interview with Kempinsky and Oppenheimer, which was filmed in New York and conducted mostly in English, is consistent with the approach he typically took in the interviews he filmed for Shoah. Lore Oppenheimer in particular conforms to the conventional expectations of the interview subject. Extraordinarily self-possessed, she has no trouble gazing directly into the camera as she recounts painful events, including the story of her familys arrival in the Riga Ghetto, where they moved into an apartment that still contained the belongings of Jews who had been torn from their homes in the middle of meals before being deported and murdered. Lanzmann periodically challenges her to supplement her narrative with facts, asking whether it was really true that there were dozens of Jewish suicides in a single day among the residents of the so-called Judenhuser (Jewish houses) in Hannover, where her story began. She directs him to look at the gravestones in the Jewish cemetery, groups of which now display the same date of death.

In terms of its thematic content, Kempinskys testimony also appears to follow a conventional format. Reading the transcript, one would not notice that anything was unusual about this particular interview. Like many of the other survivors in Shoah, Kempinsky, who was born in Kassel in 1926 to Polish Jewish parents and was thus a teenager during the war, recounts stories that must be difficult for him to tell. At the beginning of the war but prior to his deportation from Germany, he was required, as a Polish citizen and therefore an enemy of the Reich, to appear daily at the local police station on his way to school. The sergeant on duty forced him to say his name aloud, adding to his given name the obligatory Israel, the middle name that in 1938 was made mandatory by German law for all male Jews. Moreover, because Kempinskys first name was ostentatiously Germanicand because he shared it with the Reich Marshal Hermann Gringthe sergeant insisted that he repeat his name with prefatory dehumanizing epithets such as Saujude or Schweinehund. In the interview, Lanzmann asks Kempinsky more than once to repeat these appellations in German, just as he was made to do at the time, and Kempinsky indulges Lanzmanns desire for what must be a painful reenactment.

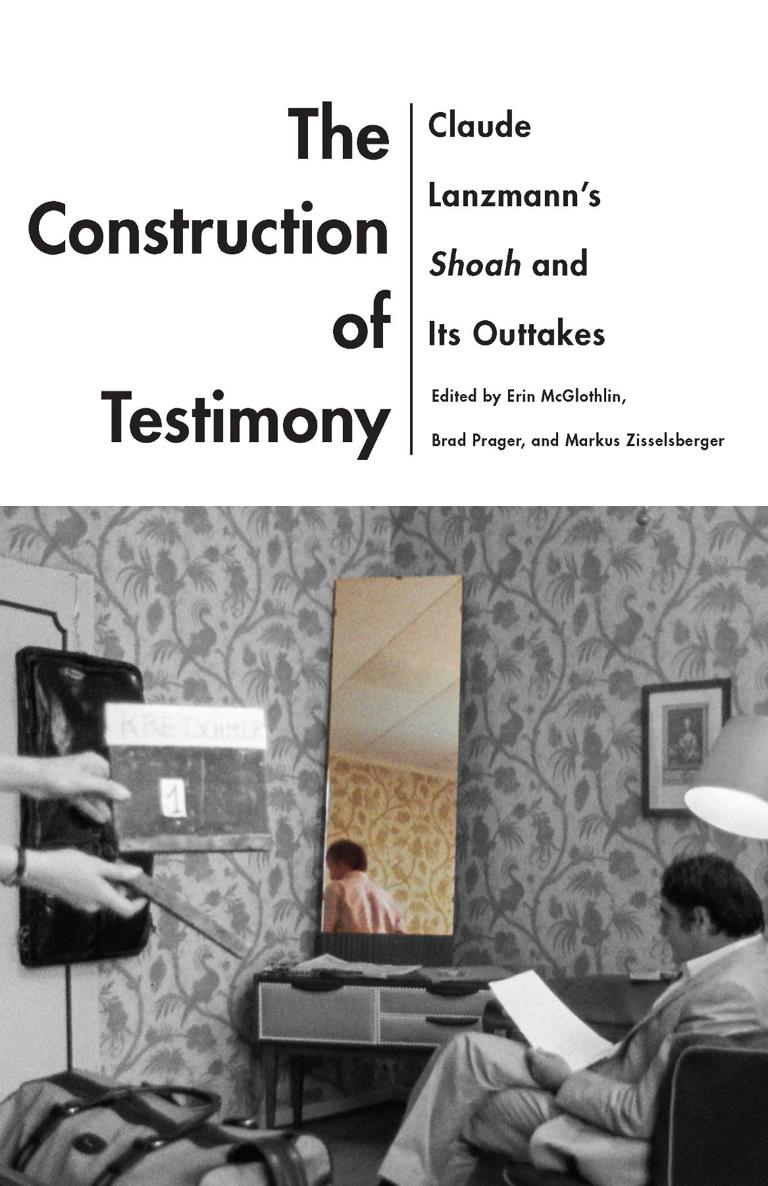

Lanzmanns interview with Kempinsky is highly significant for both its historical content and the ways in which it conforms to Lanzmanns method of provoking traumatic reenactment. But Zarwell directed us to look at the interview for an additional reasonnamely, its unconventional cinematic framing. Astonishingly, Kempinsky keeps his back to the camera as he speaks. Most of the time, we see a close-up of the back of his head in single-quarter profile, wherein the broad back of his shoulder dominates one part of the frame and his yarmulke another. This type of shot composition is hardly ideal for an interview, in that viewers can see little of Kempinskys face; indeed, it is difficult to imagine that someone who professionally documented survivor testimony would choose to conduct an interview in this way. The camera position offers viewers few conventional physiognomic signals, and for this reason we are compelled to focus on Kempinskys words and vocal inflections rather than on his movements and facial expressions. On a couple of occasions, the camera seems to pan around, searching for another angle, but it never finds a shot more comprehensive than this single-quarter profile.