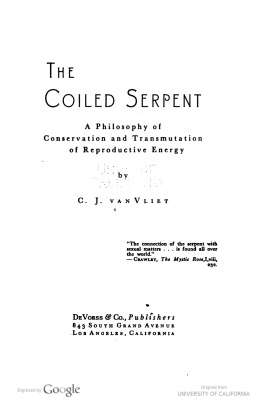

THE SERPENT COILED IN NAPLES

THE SERPENT COILED IN NAPLES

Marius Kociejowski

First published in the UK in 2022 by

Armchair Traveller

An imprint of Haus Publishing Ltd

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

Copyright Marius Kociejowski, 2022

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN 978-1-909961-81-4

eISBN 978-1-909961-80-7

Typeset in Sabon by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by Clays

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

for Chiara Ambrosio

I lived for a long while in a truly exceptional city It had everything: good and evil, health and suffering, the most joyous happiness and the most agonising pain all of these things were so tightly fused and confused, so mixed together among themselves, that a foreigner arriving in this city had, at first glance, a strange impression, as if quite normal human beings with regular instruments in the orchestra were not under the intelligent baton of the Maestro, but had wandered off to play on their own, producing an effect of marvellous confusion.

Anna Maria Ortese, Linfanta sepolta (The Buried Infanta, 1950)

Contents

1

The Serpent Coiled in Naples

Spare a thought for Jacopo Martorelli, il professore. Born in 1699, this most erudite figure was a philologist and Regius Professor of Greek antiquities at the University of Naples. We remember him, if at all, for his ability to believe absolutely in his own theories and to be unruffled by anything as trivial as solid evidence to their contrary. In 1756, he published a 738-page treatise, De regia theca calamaria (On a Royal Inkpot), complete with prolegomena and detailed notes, which drew on the recent discovery in Puglia of a bronze octagonal jar that was subsequently housed in the museum at Portici where it first tickled his imagination. I would have known nothing of the book were it not that a few years ago a copy of it strayed into the antiquarian bookshop where I work and where it is still available for inspection and improbable purchase. I shall blow the dust from it for the first comer. Its previous owner told me its chief value for him lay in the reproduction of an ancient inscription, one of several in the book, the original of which disappeared not long after publication. The book therefore provides the only proof of its former existence. Sadly I neglected to make a note of which one it was, and as this was secret knowledge that apparently only the seller was privy to, the link is now forever broken and an ancient artefact has been twice lost. Since then, the book has been the object of nobodys curiosity except, very briefly, mine. What I was able to glean of its contents came of my having had to catalogue it, and resorting to the instant information the internet provides. The book is bound in plain vellum, unlettered on the spine although there would appear to be traces of interference, possible erasure, or even, judging from the razor-like scoring in the material, excision, and it weighs roughly the same as two bags of oranges. The Latin text is liberally sprinkled with Greek and Hebrew, which makes the typography attractive to the eye. It is, I repeat, for sale. When finally somebody falls for it, which could be any time between now and forever, itll be a small miracle.

Quite incredible was the effort that went into Martorellis researches, the findings of which might nowadays fill up to ten pages of a quarterly magazine devoted to antiquities. After all, just how much can be said about an object so simple? It resembles all inkpots in that whatever it might look like on the outside, and this is a handsome enough example, on the inside it is designed to do what inkpots are meant to do, which is to hold ink. So what was so special about this one? A great deal, apparently. This is where things begin to unravel. The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, writes of his Italian contemporary that he had grasped this public opportunity of revealing everything he knows and that the gods opened for him a wide field, in which he could indulge himself in mythology and ancient astronomy. At the same time he pours out whatever can be said about inks, pens, the art of writing, and the works of the ancients. This is a polite enough verdict on a case of severe logorrhoea. The only cure that works in such instances is total abstinence because one does not whittle away such verbiage one expands, as does this sloppy old universe, with ever bigger areas of darkness between the tinselly bits and pieces.

Martorelli set out to prove, on the basis of a single object, that the earliest use of a pen and inkwell could be dated to the Jews of ancient Egypt and Greece. As theories go, it was not such a bad one a fledgling science has to begin somewhere. The Romans had their inkwells ranging from the simple terra sigillata to highly ornate ones with mythological scenes depicted on their surfaces. My hunch is that the less literary minded of them went for the more decorative style in much the same way our possessors of fountain pens inlaid with jewels tend to use them only in order to sign fat cheques or wobbly peace treaties. The Egyptians began to use inkpots when their writing shifted from stone to papyrus, which is a natural enough progression. The Jews of ancient Palestine had them too. There was one discovered in the scriptorium in Qumran. The Greeks, I dont know what the Greeks did, but presumably they, too, used them. Clearly there was a work to be written on the subject and in all probability there would be inkpot enthusiasts such as one finds nowadays for military memorabilia, tram tickets, postage stamps, cigarette cards, salt and pepper shakers, sugar cube wrappers, and barb wire. It may be reasonably assumed that in his research Martorelli did not poach the work of other scholars nor, for reasons that will become clear, would they later poach his. Were he playing forward for S.S.C. Napoli he would have had the field to himself.

So why the glum face? Sadly for him the Neapolitan government forbade circulation of his book on the grounds that it leaked confidential information on the archaeological discoveries then taking place in nearby Herculaneum, which were the province of the newly established and highly distinguished Accademia Ercolanese, the fifteen elected members among whose names Martorellis is most pointedly not to be found. Booksellers also refused to stock the title because much of it was devoted to denigrating the work of a fellow philologist and archaeologist by the name of Alessio Simmaco Mazzocchi who, incidentally, was one of the esteemed Ercolanese circle and much revered by his contemporaries. Academe, even then, was prone to mudslinging exercises. This might serve to explain the illegibility of the books title on the spine. Although it was not a work one would care to have seen on ones shelves it might have afforded private amusement all the same. We know that Herr Winckel-mann owned a copy although it is not the vellum-bound book he is holding in Raphael Mengss portrait of him. De regia theca calamaria is too cumbersome to pose with in one hand. It cant even be read in bed with ease.

Those were the very least of Martorellis troubles, however, because his theory might have held water, or even ink, had the inkpot been an inkpot and not, as was clearly the case, a jewellery box. A whole reputation was skewered on a single mistake. One can easily imagine the mortification he must have felt at seeing so much effort go to waste. One can just about hear the distant laughter emanating from the gang Ercolanese. According to the potted biography in the

Next page