Pagebreaks of the print version

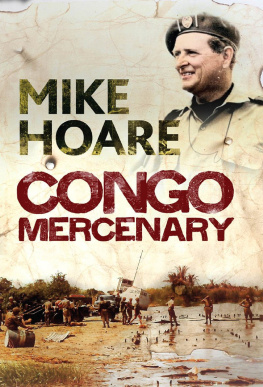

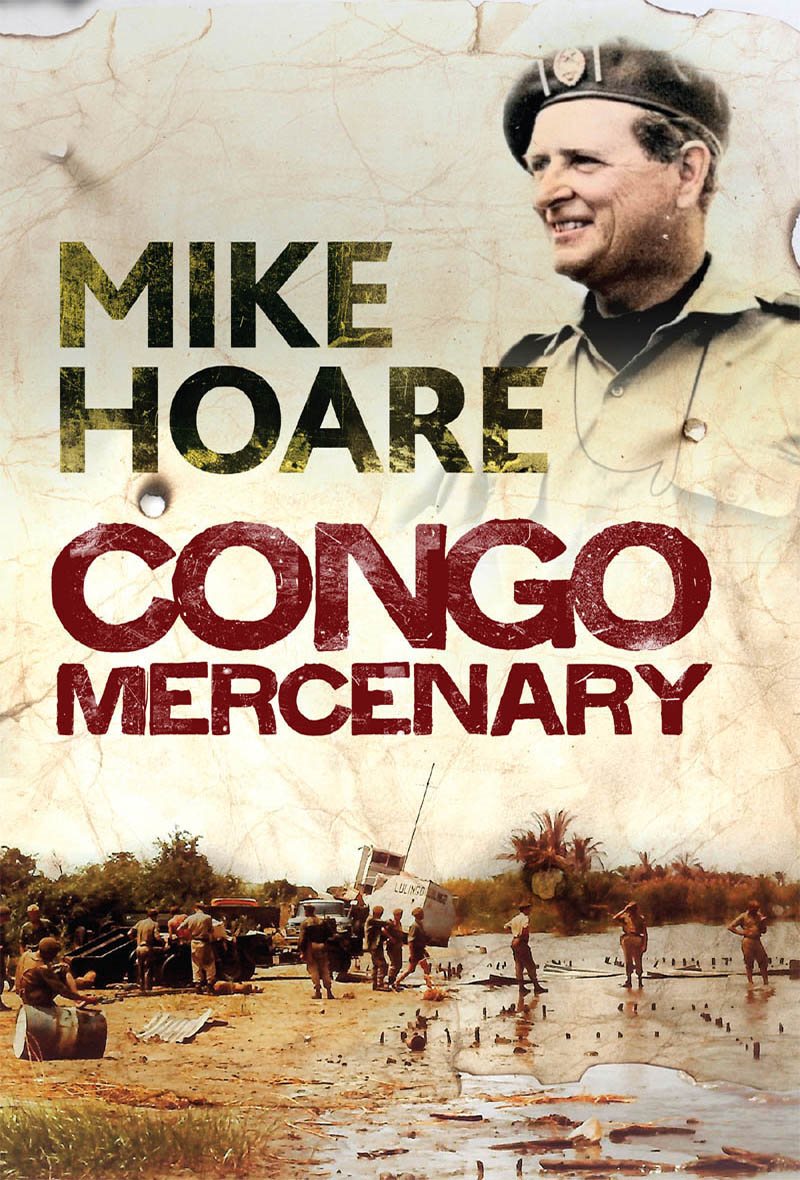

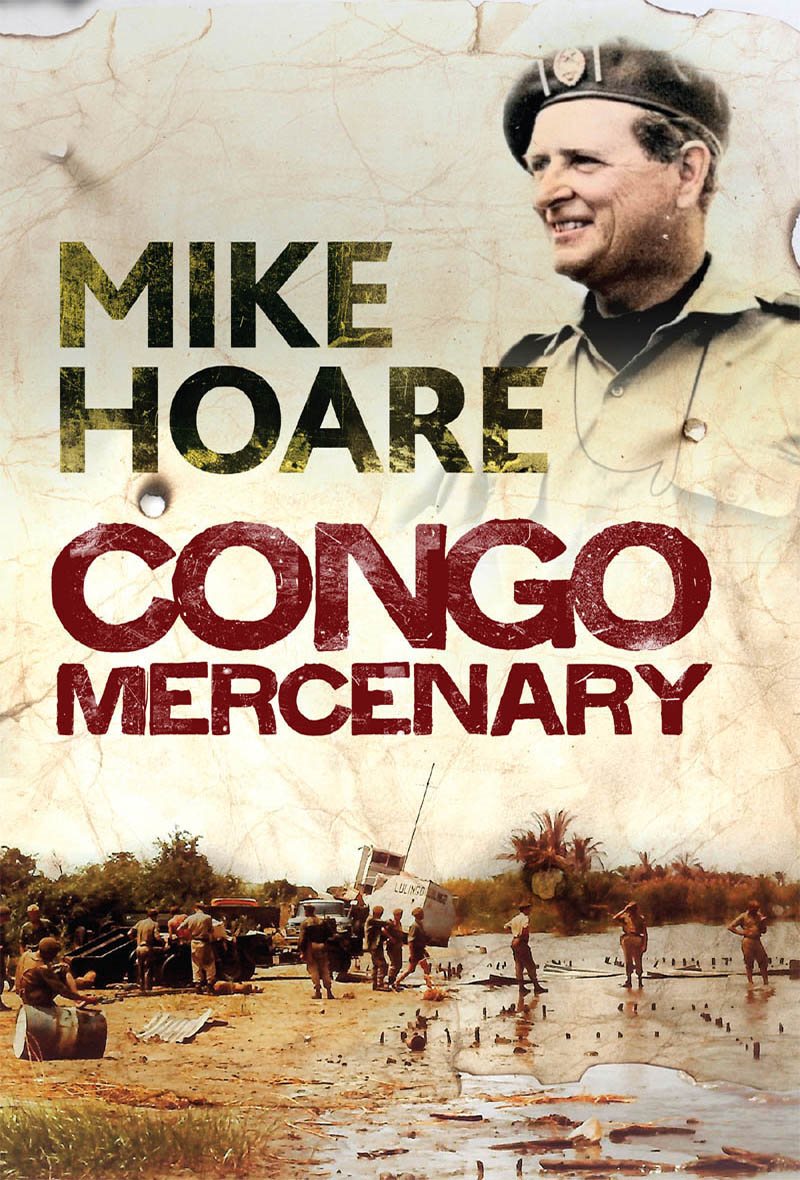

MIKE HOARE

Congo Mercenary

MIKE HOARE

Congo Mercenary

Congo Mercenary

Originally published in 1967 by Robert Hale, in 2008 by Paladin Press and in 2019 by Partners in Publishing

This paperback edition published in 2022 by Greenhill Books,

c/o Pen & Swords Books Limited,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.greenhillbooks.com

Author website: www.madmikehoare.com

ISBN: 978-1-78438-871-3

ePUB ISBN: 978-1-78438-872-0

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-78438-872-0

All rights reserved

Copyright 1967, 2008, 2019, 2022 Mike Hoare

The right of Mike Hoare to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP data record for this title is available from the British Library

FOREWORD

Joseph Dsir Mobutu was born near Lisala, a small town on the north bank of the Congo River, on 14 October 1930, and was educated at the Christian Brothers boarding school at Coquilhatville. He joined the Belgian colonial army at age 19 and rose to the rank of sergeant-major, the highest rank possible for him in colonial days. In the late 1950s, he worked as a journalist and joined the nascent Congolese National Movement in 1959. When the Congo became independent on 30 June 1960, it was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Joseph Kasavubu became its first president and Patrice Lumumba its first prime minister. Lumumba chose Mobutu as his private secretary and, soon afterwards, appointed him army chief of staff with the rank of full colonel.

Five years later, on 25 November 1965, Mobutu staged a coup and overthrew President Kasavubu without a shot being fired. Mobutu proceeded to rule the Congo with an iron hand. In May 1966, six months after he had seized power, he arrested four former ministers of state for plotting to murder him. They were tried by summary court martial and, after five minutes deliberation, sentenced to death.

On 2 June 1966, the four men were hanged in the Grand Place of the capital Leopoldville, now named Kinshasa. The crowd was estimated at more than 50,000. During the execution, an incident took place that illustrates the power that witchcraft and superstition exert over the people of Zaire even to this day. One by one the condemned men ascended the gallows to be hanged by the neck until they were dead. The last was Evariste Kimba, a former minister in the independent state of Katanga in 1963 and prime minister of the Congo in 1965.

A ripple of suppressed excitement ran through the crowd as a black bag was pulled over Kimbas head. Every person there knew that Kimba came from a family of witch doctors, famous throughout Katanga. Could he cheat death? Would he die?

The vast crowd held its breath in awestricken suspense as the rope was placed around Kimbas neck and the knot snugged down. A wave of cold fear ran through the mob. It could be felt. Not a sound could be heard. The trap door banged open and Kimba droppedonly to hang there twitching, squirming, but very much alive. A roar of disbelief rose in crescendo as Kimba was cut down and the rope placed around his neck again. Once more the trap door flew open and again Kimba droppedand again he was seen to be alive.

Panic surged through the crowd. Kimba was a witch; they knew it they had to get out of his presence at once. The terrified people surged backward and forward, kicking, shoving, and trampling each other in their panic to escape the scene. In the mle, dozens were crushed to death. The third time the rope did its grisly work.

And what of Mobutus other erstwhile enemies? What of Pierre Mulele, the man who led the rebel movement in Kwilu in 1964? His end was tragedy writ large. In 1968, Mulele was living quietly in Brazzaville, the capital of the Congo Republic, separated from Kinshasa by the mile-wide Zaire River. Mobutu declared an amnesty for all former rebels and sent envoys to encourage Mulele to return home. Persuaded by a written guarantee that would ensure his safety, Mobutus word of honour, and the presence of the presidential yacht sent especially to escort him home, Mulele decided to return. Accompanied by Justin Bom-boko, the Zaire foreign minister, Mulele returned to Kinshasa with pomp and circumstance. At the glittering reception held that night in his honour at Camp Kongolo, the army barracks, it really did seem as though all had been forgiven and forgotten.

But this was very far from being true. I quote Jules Chom, the Belgian communist author of LAscension de Mobutu , a book which caused a serious diplomatic rift between Belgium and Zaire when it was first published in Brussels: During the night the soldiers who had just come to fete him, arrested him, beat him up, tortured him, and killed him on the orders of Mobutu. It was pretended after his death that he had been tried and convicted in camera by a military court and that he was shot immediately after sentence. My eye rested on the words tortured him. If you are at all squeamish dont read on. If not, here are the hideous details. While Mulele was still alive, his eyes were gouged out, his genitals were ripped off, and his limbs were amputated one by one.

The Popular Movement of the Revolution was founded in 1967, and in 1970 Mobutu pronounced it the only political party in the Congo. Then he had himself elected president, unopposed. He ruled by decree through a Council of Ministers and began by nationalising some major industries. He diminished the power of the Catholic Church but allowed missionaries to remain, possibly because he had been educated by the Christian Brothers mission at Lisala himself. He did away with all Christian namesMobutu now became Sese Seko Nkuku Ngbendu wa za Banga, officially translated as the all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, will go from conquest to conquest leaving fire in his wake. (Personally I preferred the mellifluous Joseph Dsir.) He expelled certain foreigners, confiscating their businesses and giving them to local aspirants, although so much chaos ensued that much of this edict had to be rescinded. When the student body in Kinshasa was rash enough to demonstrate against the one-party state, they were conscripted into the army as private soldiers, never to be heard from again.

Next, Mobutu encouraged a return to African authenticity. He renamed the country Zaire, which was the original name of the Congo River. He abolished colonial place names, so that Leopoldville became Kinshasa, Stanleyville became Kisangani, and Elizabethville became Lubumbashi. He tried to develop some unity among the Congos diverse ethnic groups, an almost impossible task given the fact that the country was populated by more than 200 independent tribes. Flemish was removed from school curriculum, and French became the official language. At the same time, he encouraged the use of indigenous languages, the main ones being Lingala, Swahili, Kikongo, and Tshiluba.

Despite much turmoil and confusion, Mobutus Congo became, to some extent, a bulwark against the spread of communism in Central Africa, a matter of considerable importance to the United States in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. In the early 1960s, Chou En-lai, the prime minister of China, had visited the Sudan, Kenya, and Tanzania, a tour that caused some trepidation in diplomatic circles at that time. Probably with a view to counteracting this Chinese initiative, the United States established a CIA office in Kinshasa, headed by the redoubtable and highly efficient Larry Devlin. Shortly afterwards, Mobutuguided, without a doubt, by the United States diplomatic mission in Kinshasadeclared his support for Holden Robertos anti-communist party in neighboring Angola, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA). Mobutu encouraged the FNLA to use the Bas-Congo as a base from which to fight the Cuban mercenaries sent to Angola by Fidel Castro in support of the communist candidate, Augustino Neto.