For Sarah and Justin,

who have also loved snowfalls.

J. B. M.

For all the snow lovers of the world, wholike me

think that snow is like chocolate; there is never enough.

M. A.

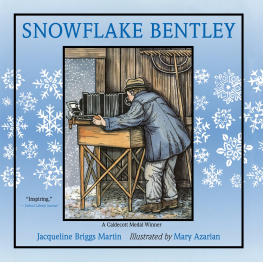

Text copyright 1998 by Jacqueline Briggs Martin

Illustrations copyright 1998 by Mary Azarian

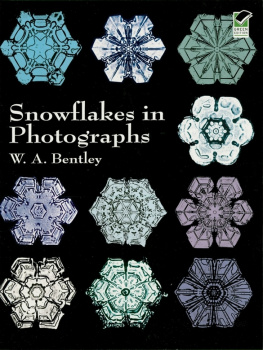

Wilson Bentleys snow crystal photographs are reprinted with permission of the Jericho Historical Society.

All rights reserved. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

I would like to thank Ray Miglionico, archivist at the Jericho Historical Society, for sharing his time,

access to the Historical Societys documents, and much information about Wilson Bentley. He is a friend to

Wilson Bentley and to all who would know more about the Snowflake Man. J.B.M.

hmhbooks.com

The text of this book is set in ITC Weidemann.

The illustrations are woodcuts, hand-tinted with watercolors.

Mullett, Mary B., The Snowflake Man, American Magazine 99 (1925), 2831.

Bentley, W. A., The Magic Beauty of Snow and Dew, National Geographic 43 (1923), 10312.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

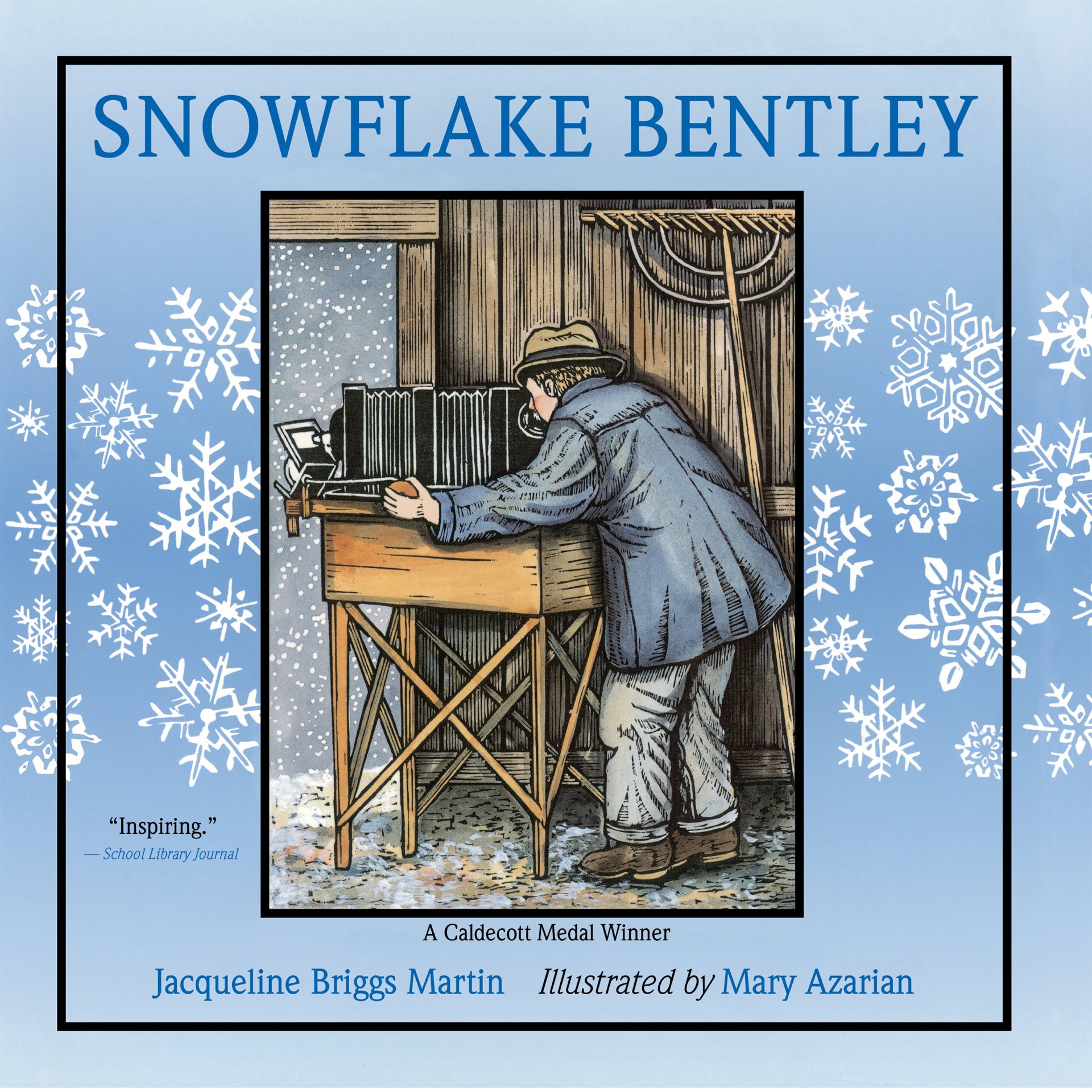

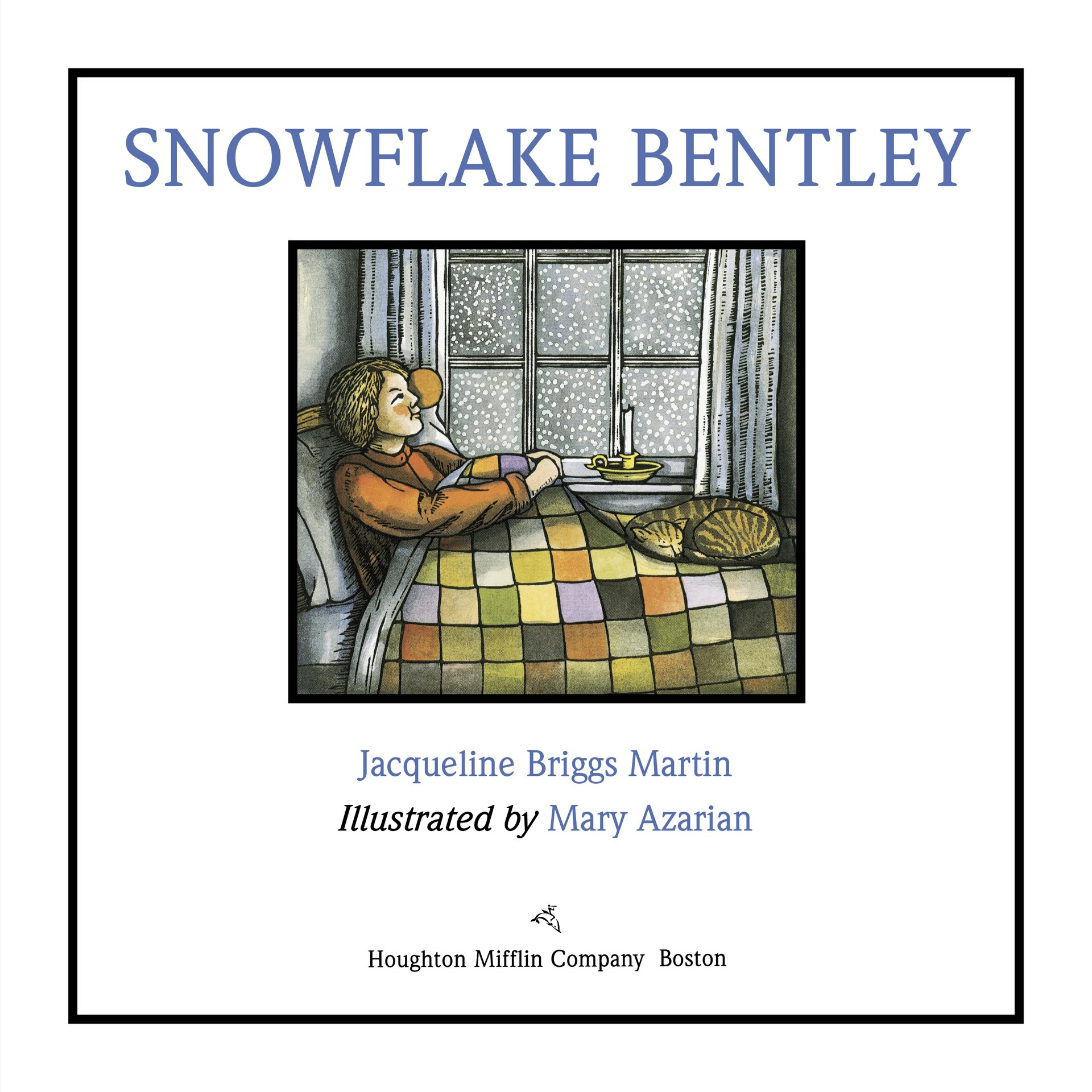

Martin, Jacqueline Briggs.

Snowflake Bentley / Jacqueline Briggs Martin; illustrated by Mary Azarian.

p. cm.

Summary: A biography of a self-taught scientist who photographed thousands of individual snowflakes in

order to study their unique formations.

1. SnowflakesJuvenile literature. 2. Nature photographyJuvenile literature.

3. MeteorologistsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature.

4. PhotographersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature.

[1. Bentley, W. A. (Wilson Alwyn), 18651931Juvenile literature.

2. Bentley, W. A. (Wilson Alwyn), 18651931. 3. Scientists. 4. Snow.]

I. Azarian, Mary, ill. II. Title.

QC858.B46M37 1998

551.57841092dc21

[B] 9712458 CIP AC

ISBN: 978-0-395-86162-2

ISBN: 978-0-547-24829-5 pb

eISBN 978-0-547-53083-3

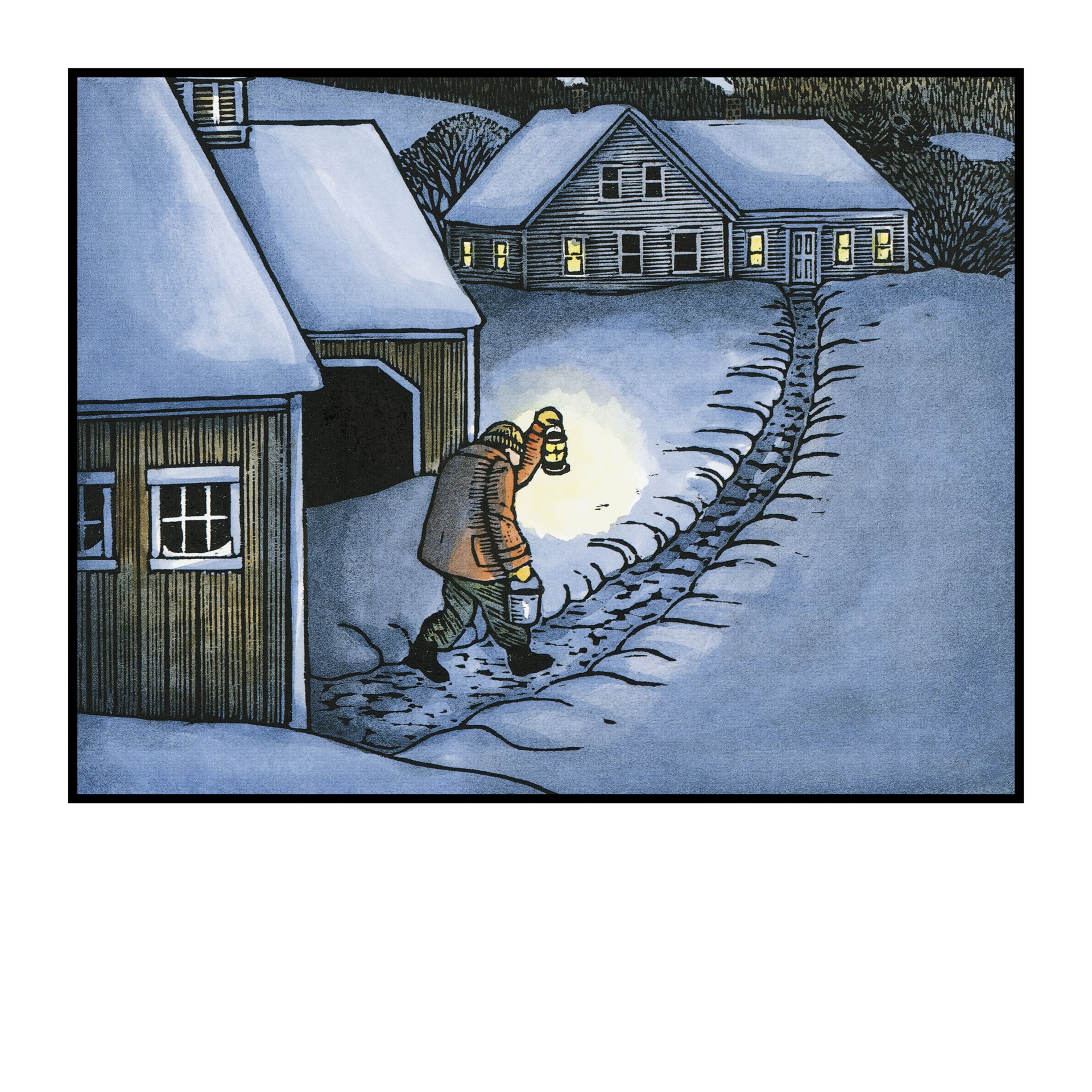

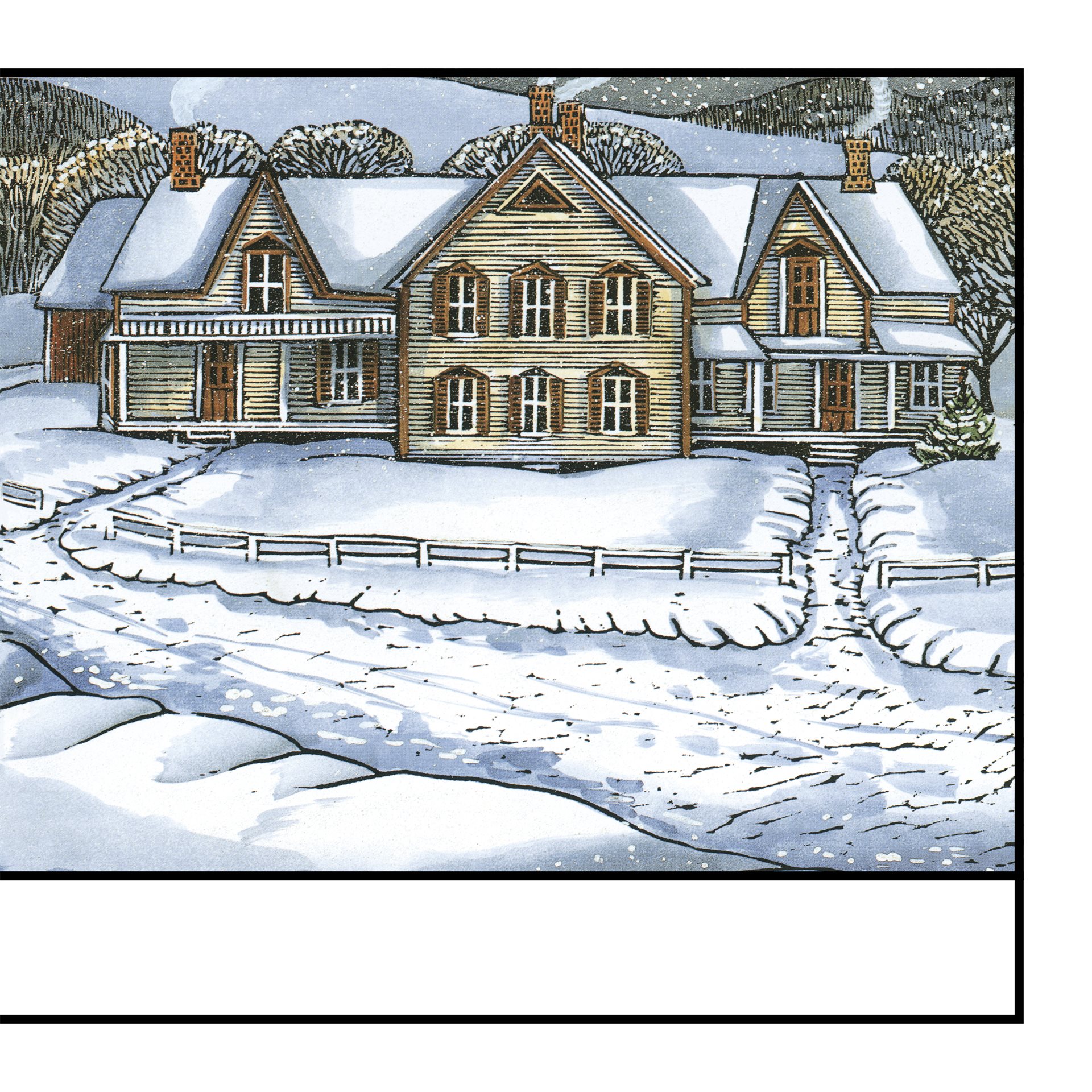

I n the days

when farmers worked with ox and sled

and cut the dark with lantern light,

there lived a boy who loved snow

more than anything else in the world.

Wilson Bentley was

born February 9, 1865,

on a farm in Jericho,

Vermont, between Lake

Champlain and Mount

Mansfield, in the heart

of the snowbelt,

where the annual

snowfall is about

120 inches.

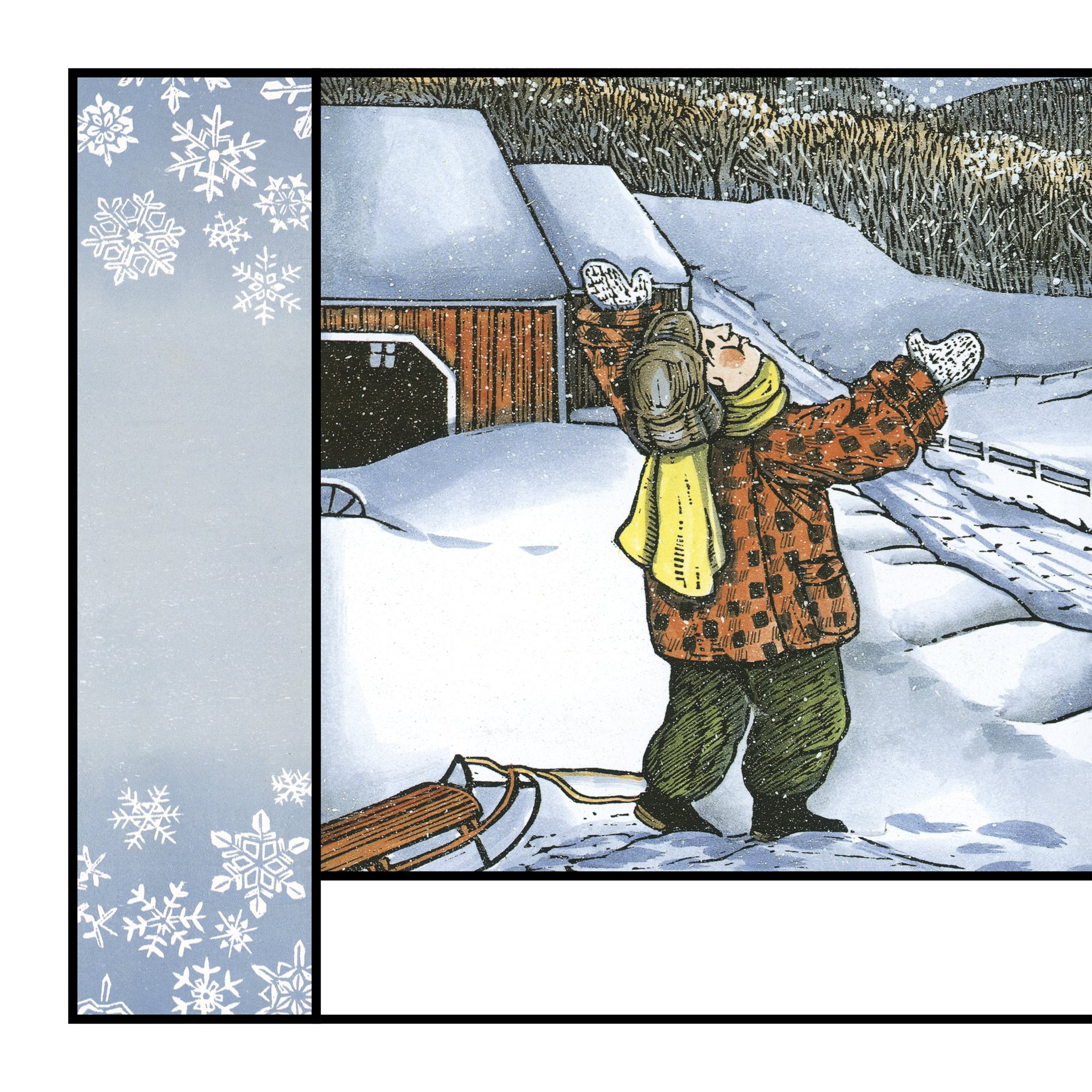

Willie Bentleys happiest days were snowstorm days.

He watched snowflakes fall on his mittens,

on the dried grass of Vermont farm fields,

on the dark metal handle of the barn door.

He said snow was as beautiful as butterflies,

or apple blossoms.

He could net butterflies

and show them to his older brother, Charlie.

He could pick apple blossoms

and take them to his mother.

But he could not share snowflakes

because he could not save them.

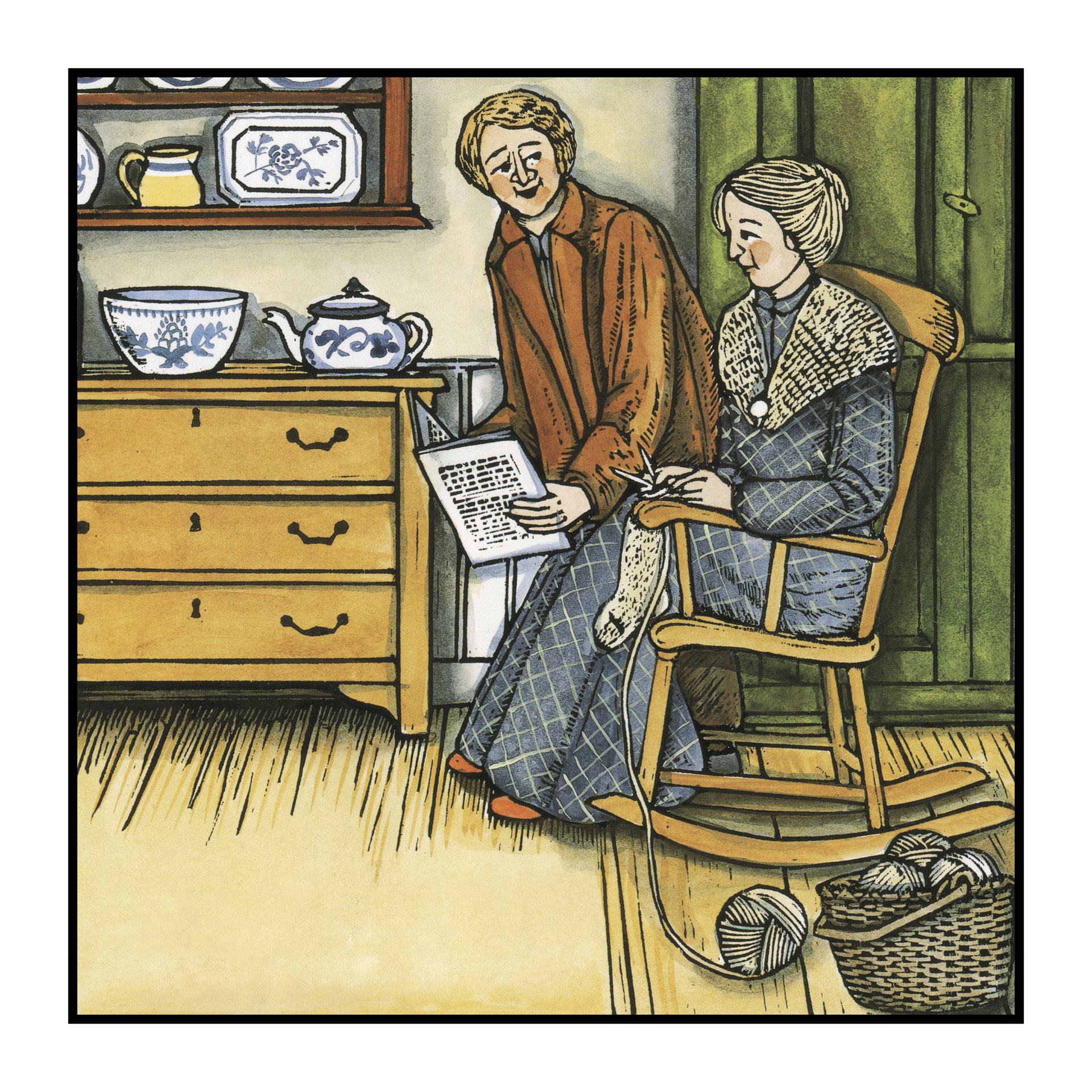

Willies mother was

his teacher until he

was fourteen years old.

He attended school

for only a few years.

She had a set of

encyclopedias, Willie

said. I read them all.

When his mother gave him an old microscope,

he used it to look at flowers, raindrops, and blades of grass.

Best of all, he used it to look at snow.

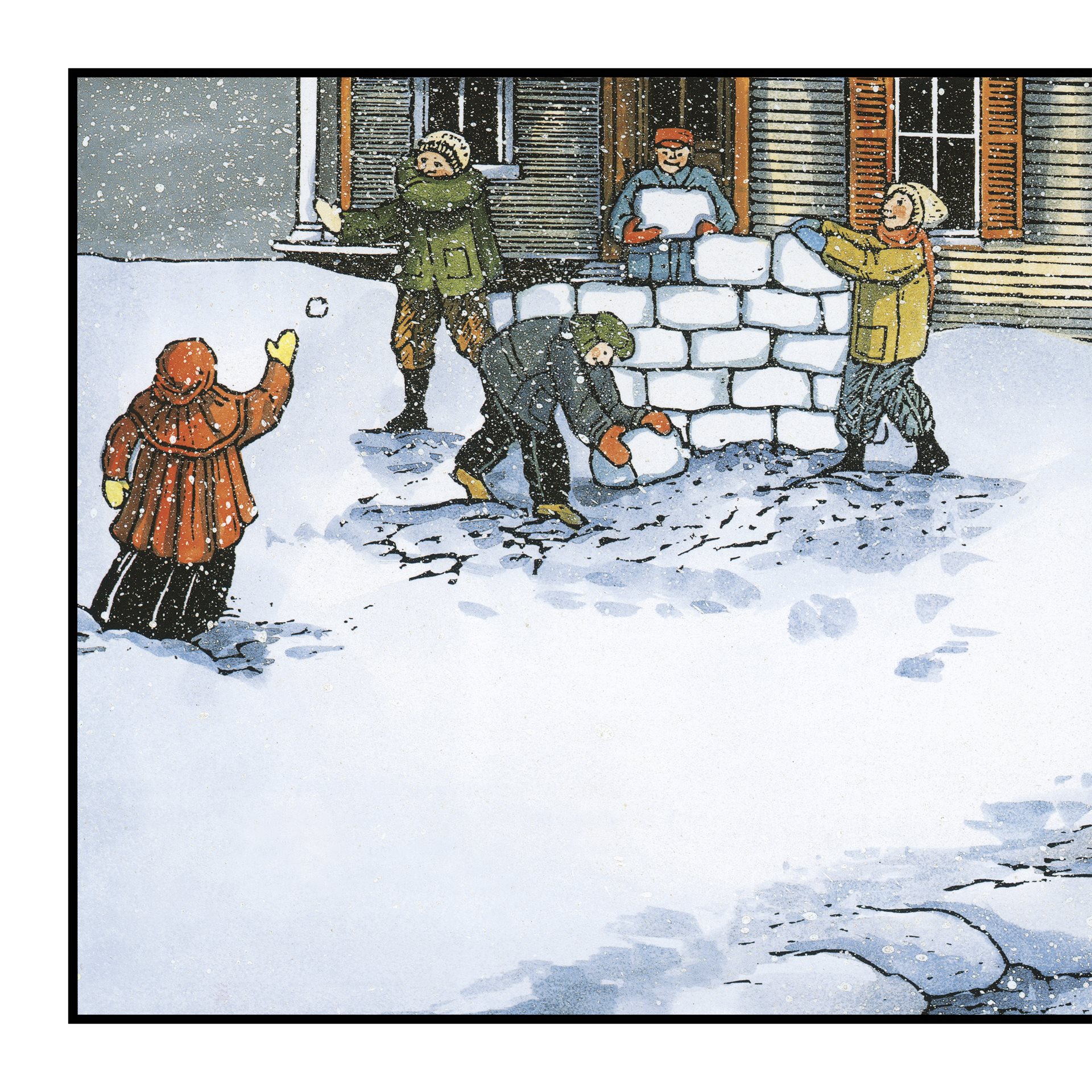

While other children built forts

and pelted snowballs at roosting crows,

Willie was catching single snowflakes.

Day after stormy day he studied the icy crystals.

From his boyhood on,

he studied all forms

of moisture. He kept a

record of the weather

and did many

experiments with

raindrops.

He learned that most

crystals had six

branches (though a few

had three). For each

snowflake the six

branches were alike.

I found that snowflakes

were masterpieces

of design, he said.

No one design was

ever repeated. When a

snowflake melted...

just that much beauty

was gone, without

leaving any record

behind.

Their intricate patterns were even more beautiful

than he had imagined.

He expected to find whole flakes that were the same,

that were copies of each other. But he never did.

Willie decided he must find a way to save snowflakes

so others could see their wonderful designs.

For three winters he tried drawing snow crystals.

They always melted before he could finish.

Starting at age fifteen

he drew a hundred

snow crystals each

winter for three winters.

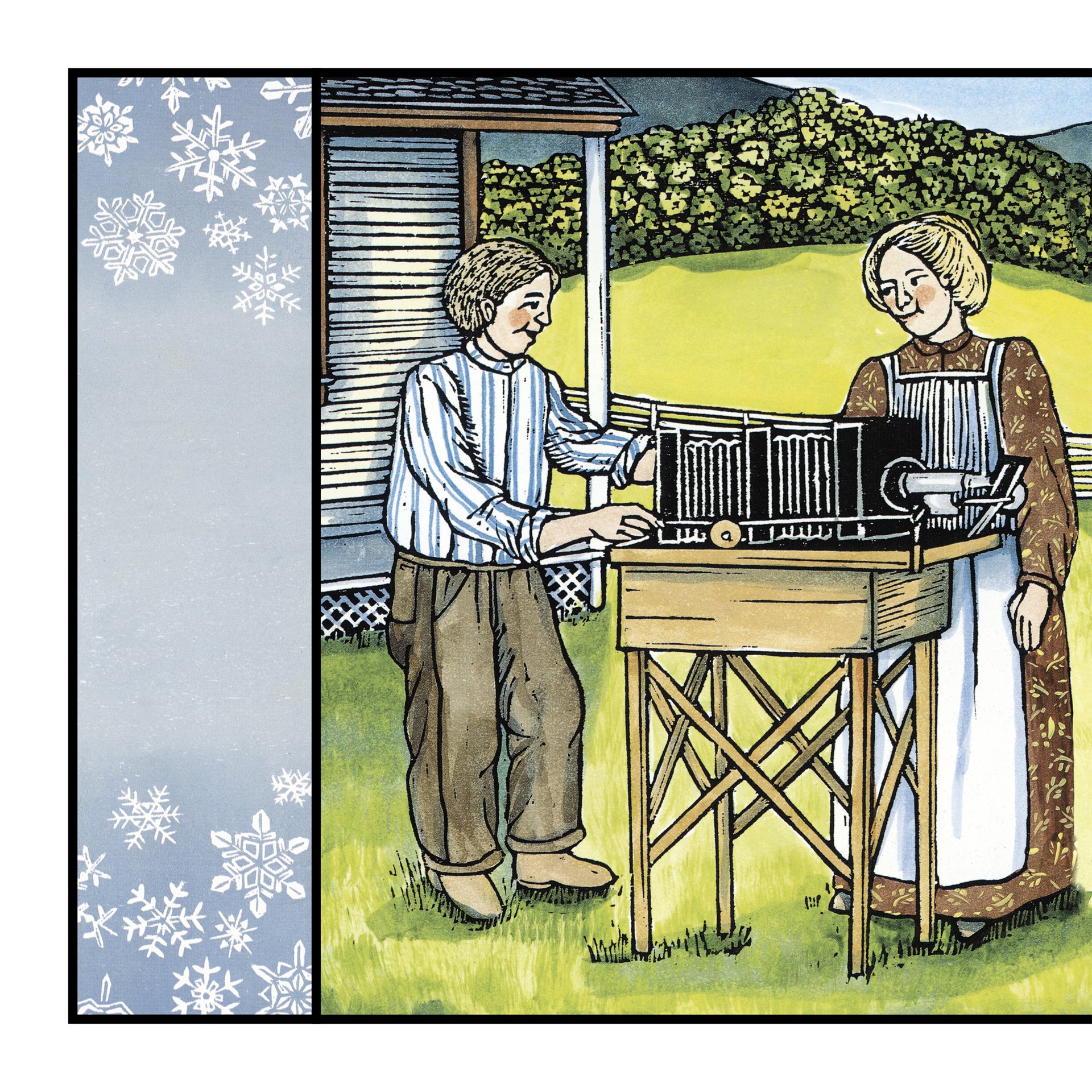

When he was sixteen, Willie read of a camera

with its own microscope.

If I had that camera I could

photograph snowflakes, he told his mother.

Willies mother knew he would not be happy until

he could share what he had seen.

Fussing with snow is just foolishness, his father said.

Still, he loved his son.

When Willie was seventeen

his parents spent their savings and bought the camera.

The camera made

images on large

glass negatives.

Its microscope could

magnify a tiny crystal

from sixty-four to 3,600

times its actual size.