Copyright Leon Hunt 2013

The right of Leon Hunt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

Distributed in the United States exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

Distributed in Canada exclusively by

UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall,

Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 0 7190 8377 8 hardback

First published 2013

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Action Publishing Technology Ltd, Gloucester

The following people read versions of some or all of the chapters in this book and offered feedback and/or encouragement: Susy Campanale, Milly Williamson, Tim Miles, Chris Ritchie, Sarah Harman and the anonymous reader of the manuscript.

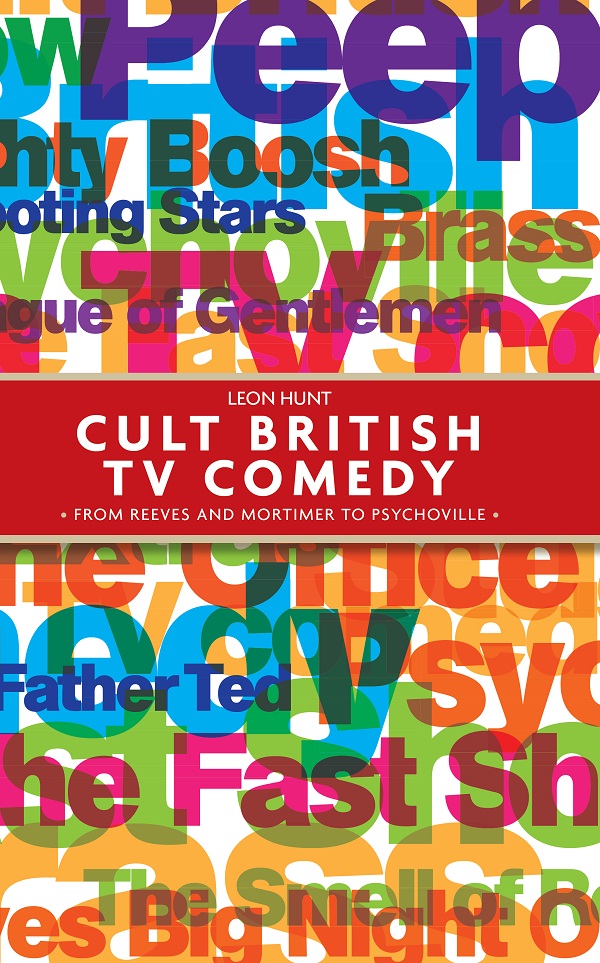

This book examines a range of cult British TV comedy from 1990 to the present. Why have I taken the early 1990s as my starting point? The subtitle of Ben Thompsons Sunshine on Putty ( But whatever ones tastes in comedy, there are good reasons for seeing this period as, if not the then certainly a, Golden Age. It produced the best work of Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer and some of Chris Morriss most controversial comedy, as well as The League of Gentlemen (BBC 2 19992002), Father Ted (Channel 4 199598) and The Office (BBC 2/BBC 1 20012, 2003). If we move beyond Thompsons cut-off point, we might also add Little Britain (BBC 3/BBC 2/BBC 1 20038), Nighty Night (BBC 3 20045), Peep Show (Channel 4 2003), The Mighty Boosh (BBC 3/BBC 2 20047), Psychoville (BBC 2 200911), Stewart Lees Comedy Vehicle (BBC 2 2009) and Limmys Show (BBC Scotland 2010), amongst others. This period has been characterized as the post-alternative era of British comedy, differentiating it from the performers (Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson, Alexei Sayle, French and Saunders, Ben Elton) and programmes (The Comic Strip Presents, The Young Ones) seen to comprise the alternative comedy of the 1980s.

This is the first sustained critical analysis of one of the richest periods in British TV comedy history. Thompsons book provides an invaluable overview of the period up to 2004, but while I am wary of polarizing academic and journalistic writing (which have more in common than tends to be acknowledged), his approach is very different from the one adopted here, often drawing on interviews and reviews that originally appeared in the Guardian. Academic writing, on the other hand, has been very selective in its coverage of the period, prioritizing sitcom and satire over other forms of TV comedy and visibly drawn to individual shows that serve current scholarly debates (The Office and the work of Chris Morris, for example). To say that there are some gaps to be filled would be something of an understatement.

This book is selective, too, of course. It emphasizes cult over mainstream comedy, for one thing however precarious, and even arbitrary, that distinction might be. Selectiveness is inevitable when examining over twenty years of TV, and when it comes to comedy, matters of taste intrude too. While I dont think it is necessary to find comedy funny in order to analyse it, it is certainly easier if it provokes some kind of reaction. Many of my favourites are here The League of Gentlemen and Psychoville, Reeves and Mortimer, Stewart Lee, Father Ted, The Mighty Boosh and The Fast Show. After reading the chapter on offence, I dont think the reader will be surprised to learn that I am not an admirer of Frankie Boyle, but I cannot deny that he has captured my attention for all sorts of reasons, he is certainly an interesting, and possibly even important, figure in recent comic history and one that it would be difficult to be indifferent to. I have neglected some important shows like The Royle Family that I admire without feeling that I had much to add to existing critical accounts of them. At the same time, while The Office has not lacked critical or scholarly attention, it was too central to my discussion of cringe comedy to leave out. Others simply slipped through the net because other shows allowed me to make much the same arguments that I might have made about them. But mostly, I have paid particular attention to series and creators who seem to me to have been (often mystifyingly) overlooked by academic studies of comedy. Such a book is fated to provoke cries of What about (insert name of show)? but my aim was never to be exhaustive in my coverage.

that of offensiveness. Cult or edgy comedy is often expected to probe the boundaries of taste while at the same time distinguishing itself from comedy that simply reinforces bigotry and hatred some comedians, like Jerry Sadowitz, have made a career out of blurring the line between good and bad offence. But offence also needs to be contextualized and so I will also look at two key moments the furore surrounding the generally well-regarded Brass Eye and the rather less clearcut ethical questions raised by Sachsgate and its aftermath. As comedians like Frankie Boyle and Jimmy Carr provoked further outrage in the media, the question of offence, its legitimacy and acceptable boundaries, came increasingly to the fore. A topic that I originally saw as a sub-section of the chapter on dark/cringe comedy grew into the chapter that most needed periodic updates. At the time of writing, Ricky Gervaiss sitcom Derek (Channel 4) focusing on a character Gervais claims is not mentally disabled is about to debut. It follows the controversy of his poorly received Life is Short (BBC 2 2011), with dwarf actor Warwick Davis playing himself, and the storm that raged around Gervaiss use of the word mong on the social networking site Twitter. The offence debate will undoubtedly change in its reference points but I suspect that for the immediate future the ethical questions will remain those examined in my final chapter on the one hand, freedom of speech and comedys right to offend, on the other hand, the tendency towards comic bullying and playing either the irony or only a joke card in defence.

Notes

An eccentric judgement, given that he praises the usual suspects from that era The League of Gentlemen, Father Ted, The Royle Family, Spaced, Reeves and Mortimer etc.