ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS:

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

Volume 25

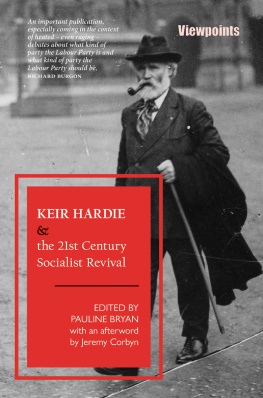

KEIR HARDIE

KEIR HARDIE

The Making of a Socialist

FRED REID

First published in 1978 by Croom Helm Ltd

This edition first published in 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1978 Fred Reid

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-32435-0 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-43443-3 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-33022-1 (Volume 25) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-44793-8 (Volume 25) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

KEIR HARDIE

THE MAKING OF A SOCIALIST

FRED REID

CROOM HELM LONDON

CONTENTS

1978 Fred Reid

Croom Helm Ltd, 2-10 St Johns Road, London SW11

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Reid, Fred

James Keir Hardie.

1. Hardie, Keir 2. Statesmen Great

Britain Biography

941.0810924$HD8393.H3

ISBN 0-85664-624-5

Printed in Great Britain by offset lithography by

Billing & Sons Ltd, Guildford, London and Worcester

PREFACE TO THE RE-ISSUE

Keir Hardies early biographers represented him as an elemental champion of his class. That reputation has not survived historical investigation. This reveals a more complex man and politician, but no agreed consensus. Here I indicate the main approaches and the differences between them.

Revision began with my 1971 essay, Keir Hardies Conversion to Socialism, in Essays in Labour History, edited by Asa Briggs and John Saville. In 1975 Kenneth Morgan and Iain McLean produced two full-length biographies, each entitled Keir Hardie and each critical of my essay. In 1978 I responded with the present book and followed up with another essay in 1983, Keir Hardie and the Labour Leader, in The Working Class in Modern British History, edited by Djay Winter. Caroline Benns Keir Hardie appeared in 1992 and Bob Holmans Keir Hardie in 2010. They attempted synthesis, but disagreed with one another.

The main issue between Morgan and myself was the influence of Marxism on Hardie. I contested the long-standing view that British Socialism owed far more to Christianity than to Marxism. I showed that Hardies idea of a Labour party was influenced by social democracy, derived from Marx and Engels. Hardie accepted two of its principles in 1887. First, he envisaged a Labour party funded by the trade unions and operating independently of the Liberal party, which opposed state control of wages and working hours. Secondly, Labour should aim to replace the Liberals as a governing party and gradually abolish capitalism. These principles were Hardies means to working-class emancipation. As to others, he was undogmatic, unlike H.M. Hyndman of the Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Thus Hardie conceived the new Scottish Labour Party of 1889 as a broad church. Funded by the trade unions and including socialists and many types of Radical. Any Labour leader must hold this broad church together around a Socialistic programme. This required rhetorical eclecticism and tactical flexibility. Hardie was adept at both and used his skills to advance the cause as he conceived it.

Kenneth Morgan, by contrast, argued that Hardies views owed everything to his conversion to Christianity in 1878, not his interest in Socialism around 1887. 1887 was no sharp break. Hardies idea of a Labour Party owed as much to his Radicalism as to Socialism. He took time, however, to understand that progress required collaboration with the Liberal party. His extreme independence in Parliament between 1893 and 1895 was a mistake, contributing to the disastrous defeat of the Independent Labour Party, formed in 1893. Slowly, with the collaboration of Ramsay Macdonald, he learned to exploit his Radical credentials. With Hardies support, Macdonald was able to make an electoral pact with the Liberals in 1903, through which the Labour Representation Committee gained a Parliamentary foothold as the Labour Party in 1906.

I still take issue with this interpretation. Hardie, unlike Macdonald, never believed that Labour should accept any kind of Progressivist alliance with the Liberal Party. His aim was always to build up a trade union based Labour party, able to force the Liberals to give ground in constituencies where it was strong. That was his aim for the Scottish Labour Party, but it proved too weak to force such a bargain. In 1903, however, Macdonald could bargain with the Liberals from a position of strength. Anticipating a close electoral fight in 1906, they saw advantage in conceding constituencies where Labour had a greater chance of winning. But, whereas Macdonald assured them that most Labour candidates had no fundamental disagreement with Liberalism. Hardie always maintained that they had. He believed in an imminent Liberal split and urged Radicals to join the Labour Party.

Benn and Holman acknowledged the influence of social democracy on Hardie, but left other topics unresolved: Hardies commitment to gender equality; the extent of his support for colonial independence; the contradictions in his so-called pacifism. In this book I touched only lightly on these issues. I paid more attention to another, his reputation as Member for the unemployed. Hardies favoured policy was to send them to farm colonies, to produce their own subsistence. This led him to some dark conclusions. Like many right-wing ideologues, he preferred farm colonies to unemployment benefit, because loafers would spend benefit on drink. Like eugenicists, he believed farm colonies would prevent the unfit from multiplying: Treat them as you will and, above all, see that it is made impossible for them to propagate their species. (168)

This is not to denigrate Hardie, but to show that we cannot adopt him simply as a universal hero. Every Labour tendency can construct its own Keir Hardie as these biographers do: the broad church; Socialist momentum; Christian Socialism; political pragmatism. Each approaches him with a different ideal of a Labour Party. This should stimulate research but not consensus. Hardie is not one of us. He belongs to a different age. He was a Victorian, with all the ideological baggage that implies. Consequently, he belongs to history and to no political movement of the present time.