This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1947 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

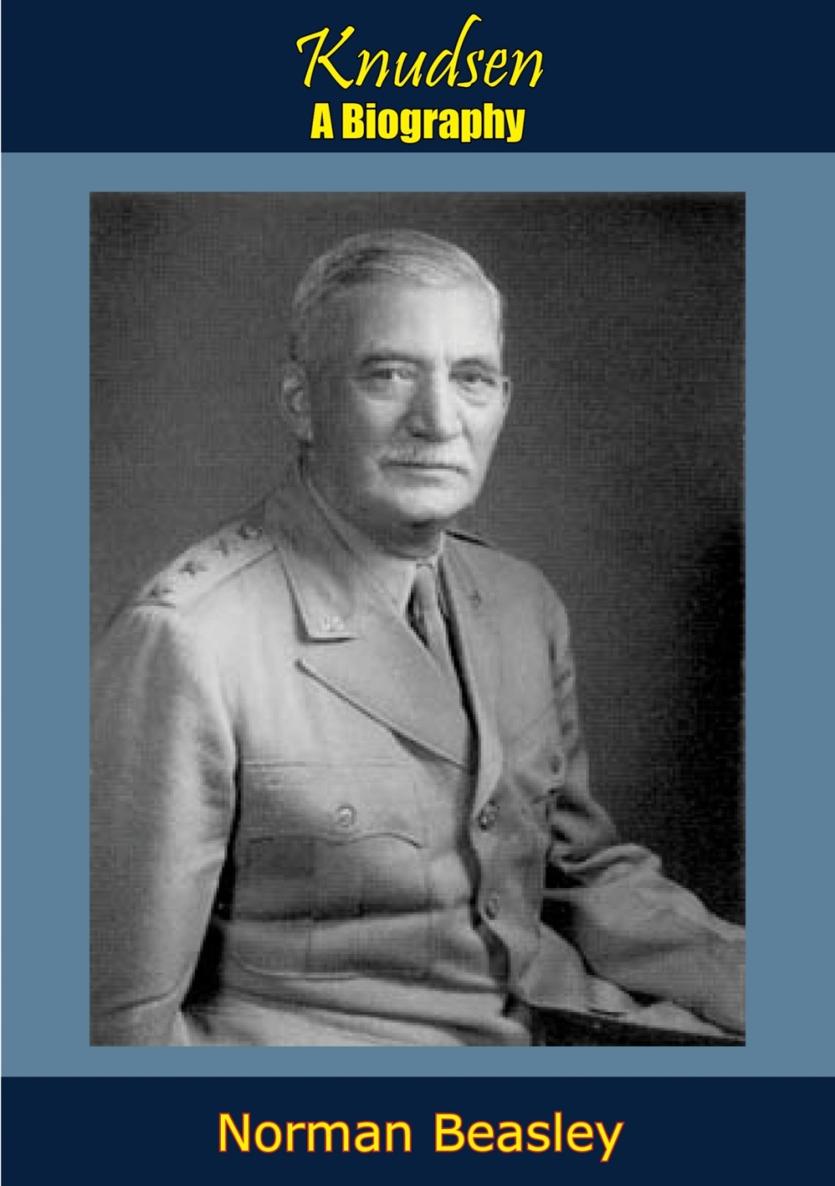

KNUDSEN: A BIOGRAPHY

BY

NORMAN BEASLEY

INTRODUCTION

IN PRESENTING a period of forty-seven years in the United States, the picture divides itself into three periods.

The first period of twelve years might be considered apprenticeship in factory production operation.

The next twenty-eight years, or the second period, presents a development period in industry in the United States, the birth of mass production and an industrial prosperity, which is a natural sequence.

The third period, or the last seven years, presents the war and its influence on the American life and economy.

The first period was a sort of awakening. The invention and the perfection of the motor car had a tremendous influence over the whole world and procured for America prestige as the cradle of transportation.

Manufacturing was more or less, at the beginning, by the hit-and-miss method. Prices were low, wages were reasonable, and output was sufficient to obtain the necessities of life. Joys were simple and inexpensive; men were strong and had definite opinions as to what life ought to be and as to the means of obtaining it.

America was growing.

Immigrants came in by the hundreds of thousands every year. The farms were reinforced by the influx of men who had knowledge and physical strength to develop the farm and its products.

Government interference was unknown. In fact, individualism reached its zenith during that age and laid the foundation that later was responsible for the extensive development of production.

Manufacturing was helped tremendously by inventions. The American standard of living was advancing rapidly and by the time the second era of mass production was ended we were practically on top of the rest of the world. Everything was growing and everyone was striving to do better at his daily task. Panics were few and small. Reaction to panics was quick and left but few scars on the economy.

Then came the second period, which lasted until the beginning of the Second World War, and during which much of Americas work was created by the demand for comfort and better living. During this period luxuries began creeping into the productive lives of our people.

The boom market of the twenties created a desire for luxuries which was gratified to the fullest extent until the panic of 1929. Then Americans more or less stopped praying to materialism and began to take an interest in the other fellow.

With the prosperity of the twenties came an upswing in the desire for education. All young people were herded into schools of all sorts, and were taught about theoretical happiness instead of about the value of work to pay their taxes and to pay their debts.

When troublesome times came, politics took a sudden interest in what to do to live without working, and a brand new set of teachings came into the life of America. Doles, boondoggling, and government spending were tried. Although these failed utterly, they left a thought in the minds of men that there might be something to them. The family of breadwinners got constantly smaller because the youngsters had been told that manual labor was a detriment to the educational potential ability in this new and better world.

The labor movement, which had been growing steadily on a craft basis, suddenly became the father of the industrial union, where the monthly dues furnished the only qualifications needed to herd people into large numbers, and gave the agitator a chance to harangue and assure that this New Deal was something that was going to make it possible to get something for nothing.

Industry or, rather, the employers were more or less stupefied; as to the government, it took a hand in the argument and proceeded to give labor preferential treatment while the employers had no chance, even in the United States Supreme Court, to be heard or given consideration. The result was that prices went up, and the production picture was lammed when employment became stationary and only the impetus of war brought back a semblance of prosperity.

Unemployment was cured by taking a large number of producers and placing them in the Army as well as the Navy. The resulting labor shortage raised the price and the cost of labor; and government cheerfully helped it along, using the war as a medium for getting it across.

Industry and agriculture in America responded to the tremendous impetus of fear of the war and rose to the occasion of producing a worlds record in war material.

New engines of death were invented and the education of industry, which hitherto had tried to produce goods at low cost, turned right around to produce quality death merchandise at tremendous speed and at costs on a poundage basis never heard of before in American industry.

The volume made the production possible and took the sting out of the high cost, and victory ripped out the remainder of the worries on that score.

Our young men who went to war had no particular experience in war on a scale as conducted by our leaders. They were aggressive and out-of-patience with the principles by which the enemy conducted warfare and, after getting enough material, proceeded to put in a few ideas of their own in the conduct of the war, conquering the stereotyped methods of war as was known from the textbooks of warfare in other parts of the world.

The successful ending of the war and the occupation of foreign lands came. The problem is still with us as to how to clean them up as we would clean up our own land. We find there other people of other thoughtseven among the victors there is a dispute as to what to do with the conquered people. The attempt to control conquered nations with American methods has brought confusion into the picture, and there is passive resistance to everything we want to dobe it right or wrong. The orator has supplanted the soldier and the orator cannot prescribe the remedies for the situation we are in by picking one thing at a time.

Minorities over the world have a field day and, by screaming famine and sickness, complain about conditions that they would have been very happy to impose on the victors, if they had won the war. It is hard to forecast how long this period will last.