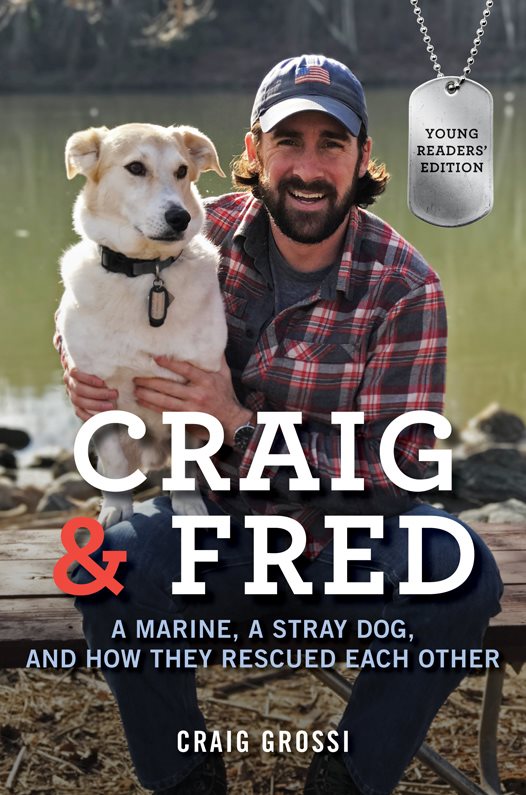

IT WAS ALMOST MIDNIGHT when our helicopter arrived in Sangin, Afghanistan. In the final moments before we touched down, no one spoke. We secured our packs and turned on our night-vision goggles. We were about to be dropped several miles from a compound that would become our base. There was no time to waste: We had to hike to the site, then spend the rest of the night filling sandbags and preparing for the attack that would almost certainly come at sunrise.

I was an intelligence collector for the United States Marine Corps, so my job was to learn as much as I could from the villagers about the Taliban, the fundamentalist political group that was waging war in Afghanistan. If we captured a Taliban fighter, I was the only one in the unit who could question him.

The guys I was heading out with were Recon marines, reconnaissance forces. My expertise was in communication; theirs was in combat. They were the real dealan elite force of special operations guys who were tough and experienced. They were like professional athletes, and smart, too. To earn their trust, I needed to prove that I was able to keep up on long nighttime patrols and in gunfights. I also needed to show that I brought something to the battlefield that they couldnt provide themselves.

I had been on another mission in an agricultural town in southern Afghanistan, but I knew this was going to be a different fight. In the previous mission, I had served with a British Royal Marine named Jack. He was supposed to come with us to Sangin, but he changed his plans.

Im not going back there, hed said. He had served there a few years earlier when British forces first secured the area. Its the kind of place where you turn a corner and theres two Taliban guys standing there. Ones got an RPGthats a rocket-propelled grenadeand the others got a machine gun, and theyre just waiting to light you up. The place is bonkers.

Sangin had that reputation. The Taliban were bolder there because it was an important location for poppy farming, and the opium trade helped fund the Taliban. We expected them to have a lot of fighters and a lot of firepower.

The Taliban controlled the families in the villages, who had no other choice but to go along with what they were told. The Taliban took what they wanted, shutting down the local economy. These villages were extremely poor. Often, the Taliban were the only ones who owned anything of much material value, from sneakers to cell phones to the little Honda motorcycles they drove around. When they needed food, theyd show up at markets and bakeries and take what they pleased. If a motorcycle broke down, theyd find the only mechanic in town and take the parts or make him fix the bike at gunpoint. They ruined weddings, breaking musical instruments and punishing guests for dancing. They recruitedor just tookyoung boys to join their forces.

With a thud, the helicopter landed in a cloud of dust. We stepped out into the night, rifles up. The desert earth was firm under my boots, and a thin layer of silky dust washed over everything like water. I tried not to cough. The helicopter rotors whipped up a heavy haze of dirt before lifting the vehicle back into the sky. Theres nothing like the sound of that hum disappearing into the distance. At that point its just you and the guys on the ground, with no machine to protect you or whisk you away. Thats when it gets real.

We started moving, single file to avoid IEDsimprovised explosive devicesand bombs. All I heard was the sound of our boots scuffing against the dirt and our packs shifting on our backs. With very little light pollution, Afghanistan is supposed to be ideal for stargazing, but the dust in Sangin never settled. Overhead the dark sky looked like a smudged impressionist painting.

We walked two or three miles, over rolling hills, heading west. In all, there were about sixty guysthree platoons of marines, plus attachments like me and the Explosive Ordnance Disposal team (EOD) trained to find and dispose of bombs, as well as members of the Afghan National Army. Our gear and backpacks were heavyseventy pounds or morebut we were well trained. After a while, my heart rate steadied as my body got used to the idea of being in Sangin.

When we came up to the compound, we saw an elderly man waiting in the doorway. We only established bases in compounds that were occupied. If folks were already living there and hadnt been blown up, that was a good sign that the place wasnt rigged with bombs.

Ali, the interpreter on the mission, and I walked up to talk to the man. Ali had been on the previous mission with me, and wed gotten close. He was from Afghanistan but had moved to the United States years ago. Now, hed returned to help his homeland, and to make a decent living for his wife and newborn baby back in Arizona.

We approached the villager and shook his hand. I explained who we were and that we were here to helpand that we would need his family to move to another compound. Often, families like his were nomads, moving from place to place to work as sharecroppers. In this case, the elderly man told us he and his family hadnt been there very long, and he kindly agreed to relocate.

He opened the small metal door, and we filed in. Some of us got to work preparing the compound, while others helped the man and his family move a few hundred yards away to a neighboring site, bringing their cows and goats with them.

The compound was large. Its thick mud walls were about twelve feet high. Inside, there were a few basic structures, like little hutssmall buildings made of packed mud. We spent the night filling green plastic sandbags, assembly-line style. Using a collapsible shovel, I scooped dust and dirt into the bags, then another guy would carry them over to the marines on the roof, who would hoist them onto the tops of the clay buildings. The sandbagswhich were bulletproof when filledwere used to build a shield to protect the guys while they fired on the enemy. Down below, we dug small windows into the main wall so that we could see out and shoot to defend ourselves.

We worked all night. When the sun came up, I could see the wide, sweeping desert that stretched out to the east. To the west, the compound overlooked Highway 611 and, beyond it, the Green Zone. We called it the Green Zone because thats where the Helmand River flowed, giving way to lush, green farmland. Fields of corn and poppies spread out on either side of the river, along with an extensive network of irrigation canals.

Highway 611 was actually a dirt road that ran north to south. It was a regular site of bomb attacks. The highway divided the irrigated land in the Green Zone from the scorched desert where we had established our post.

The Taliban controlled the Green Zone. Our mission was to drive them out so that coalition forcesengineers and soldiers from the United States and other countries working to bring peace to Afghanistancould safely make their way up Highway 611. After the area was secured, the road could be cleared of bombs, allowing a much-needed generator to be delivered to a dam in the north. Once functional, it would provide electricity to the entire region.

Sangin is so remote and rural that many Afghan people refuse to go there. Its tribal land, home to fewer than 15,000 residents, most of them farmers who live largely without access to formal education or electricity. Thats part of what makes the region so susceptible to Taliban abuse and control.