Table of Contents

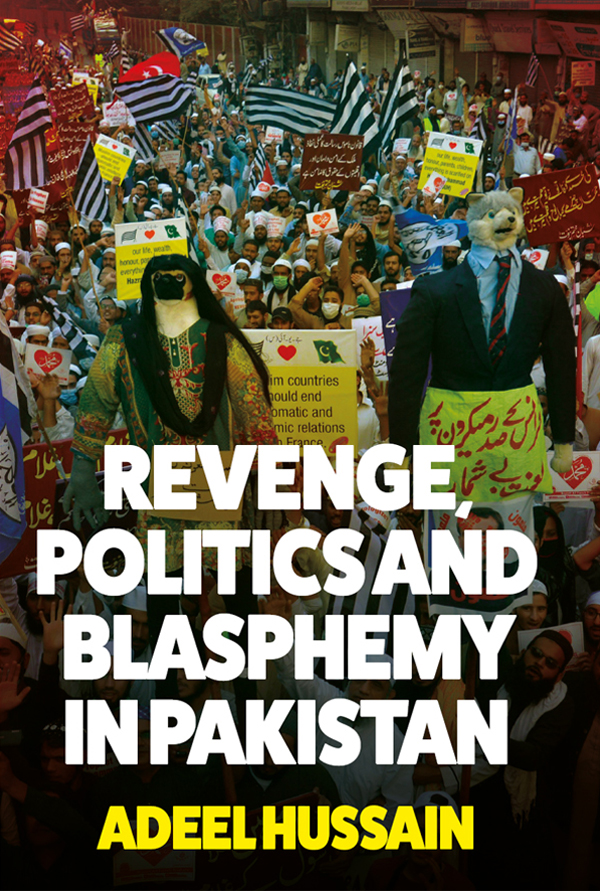

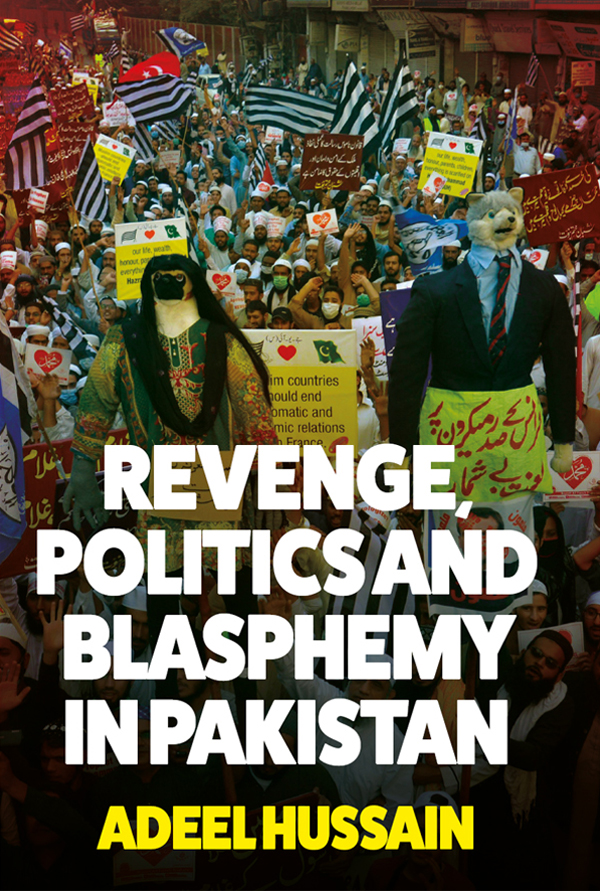

REVENGE, POLITICS AND BLASPHEMY IN PAKISTAN

ADEEL HUSSAIN

Revenge, Politics

and Blasphemy

in Pakistan

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2022 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

Copyright Adeel Hussain, 2022

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United Kingdom

The right of Adeel Hussain to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787386853

www.hurstpublishers.com

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would first like to thank Shruti Kapila. Shrutis deep scholarly insights into the history of South Asia were critical in my intellectual development. Anshul Avijit has been an intellectual companion for my entire journey into the subcontinent and has contributed to the development of the arguments in more ways than I can acknowledge. Siraj Khans invaluable comments on early drafts have significantly shaped this book, and I thank him for his continued friendship and intellectual generosity. Tripurdaman Singh has offered important input throughout the writing process. Faisal Devji has been a constant source of inspiration and support over the last decade. His writings on Muslim thought and the nationalist moment remain foundational for this book and my broader thinking on South Asia. As always, Tahir Kamran has provided crucial insights on an early manuscript draft and has offered support throughout my academic career. Armin von Bogdandy provided a hospitable academic home at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, where this book took root. Alastair McClure has offered insights into the legal structure of colonial India and helped mould the argument of the first part of the book. The late Sir Christopher A. Bayly provided helpful guidance and encouragement in my early scholarly engagements with South Asia, and he remains a model for intellectual integrity. I would also like to thank Simon Wolf, Adam Lebovitz, Samuel Zeitlin, Saumya Saxena, Tilmann Rder, Jonah Schulhofer-Wohl, Jojo Nem Singh, Daniel Thomas, Letizia Lo Giacco, and Thomas Clausen for their friendship and support.

Michael Dwyer has been a publisher extraordinaire. I thank him for believing in the potential of this book and for bringing it into existence. The anonymous peer-reviewers have greatly enhanced the scope of this book, and to work with the editorial team at Hurst has been any authors dream. To complete this book, I have benefitted from institutional support at the University of Cambridge, the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, and Leiden University. I would also like to thank the archivists at the libraries I consulted for this research.

My parents and sisters have encouraged and fostered my intellectual curiosity, for which I remain forever grateful. My wife, Mariam Chauhan, who is also my most critical reader, has helped me finalise this project and offered important advice at all stages of writing the book. I dedicate this book to her. Unless they formed a crucial part of a legal case, blasphemous assertions against the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) have not been repeated. As per scholarly convention in academic works, the Islamic honorifics for the Prophet Muhammad have been omitted.

Leiden, March 2022 | ADEEL HUSSAIN |

INTRODUCTION

Sometime in 2015, Tahir Naseem, a taxi driver in his early fifties from Illinois, began receiving dreams he believed were from God. Naseem had come from Pakistan to the United States more than thirty years previously to escape the persecution of the religious sect to which he belonged, the Ahmadiyya. This sect put an enormous emphasis on dreams. In most of their yearly gatherings, the spiritual head of the Ahmadiyya, the caliph, who is usually a descendent of their nineteenth-century founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, would read out dreams of his followers at great length as proof for the groups divine connection. A large number of these dreams were merely personal journeys of converts. Others related to more earthly matters like health, career, family, and education. Yet, there was a line in the narration of these dreams that was not to be crossed: dreams in which God disclosed theological insights were reserved for the caliph alone. Naseems spiritual visions, however, were of this nature. They increasingly mirrored those of the sects founder. Naseem began to publicly claim that he was a spiritual reformer, a mujaddid, and soon after upped the stakes and asserted that he was the Messiah and a prophet, too.

Naseems claims were no longer compatible with Ahmadiyya teachings, and he soon left the group to accept a following of his own. He amplified his spiritual message through social media and plugged himself into a circuit of spirited fellow travellers. This group consisted of other self-proclaimed prophets, zealous conspiracy theorists, diligent hobby theologians, and members of other cults who were now holding their spiritual leaders to task by radically challenging the very premises of their former beliefs. Many of them had South Asian roots and they would meet online to debate the latest visions they had allegedly received from God or share insight on scriptural references they felt confirmed their exalted status.

Many of their conversations ended up on YouTube. In one such debate, from May 2018, Naseem discussed his mission with Zahid Khan, another aspirant to prophethood. After assessing their relative status as prophets and generously conceding that there could be more than one prophet on earth at the same time, Khan, who had grown up in Lahore, urged Naseem to cancel his upcoming missionary trip to Pakistan. They will do worse things to you in Pakistan than the Jews did to Jesus, Khan pleaded from his living room in Frankfurt, perhaps hoping that the reference to earlier prophets would dampen Naseems drive to carry his message to the motherland.

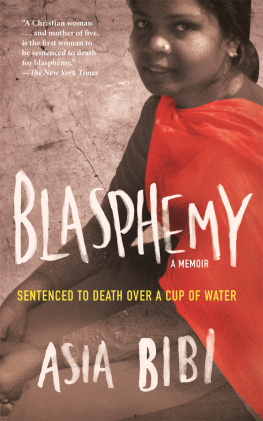

Despite these explicit warnings, Naseem flew to Peshawar, an ancient city bordering Afghanistan along the eastern edge of the Khyber Pass. As expected, Naseem failed to convince anyone of his prophetic status. Instead, he quickly ran into problems with the law. After preaching to a teenager at a Peshawar mall, he was put in jail on charges of blasphemy. The boy, a madrassa student, testified that Naseem had first contacted him via Facebook and claimed to be a prophet. Later, Naseem had repeated this statement at the mall, where they had met for ice cream. In Pakistan, a country with strict blasphemy laws, any claim to prophethood is punishable under criminal law. It violates section 295 of Pakistans penal code, where a series of anti-blasphemy laws enshrine offences against religion and seek to punish any blasphemous expressions against the Prophet Muhammad with a mandatory death sentence.

In July 2020, after more than two years of solitary confinement, Naseem appeared before the Peshawar High Court. Around the same time, his videos began to receive renewed attention, and his view counts on YouTube soared. A swarm of members from the Tahreek-e-Labaik Pakistan, a political party with the primary purpose of hounding blasphemers and avenging insults against the Prophet Muhammad, was fuming in the comments section. Naseems claim to prophethood, they alleged, had violated the theological principle that the Prophet Muhammad is Gods last Prophet, a principle enshrined in the sacred Quranic doctrine of