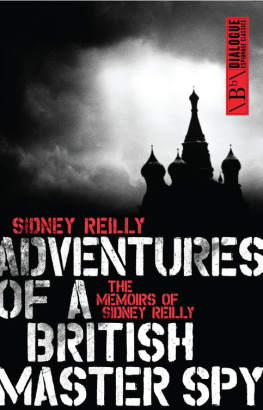

Phocion Publishing 2019, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

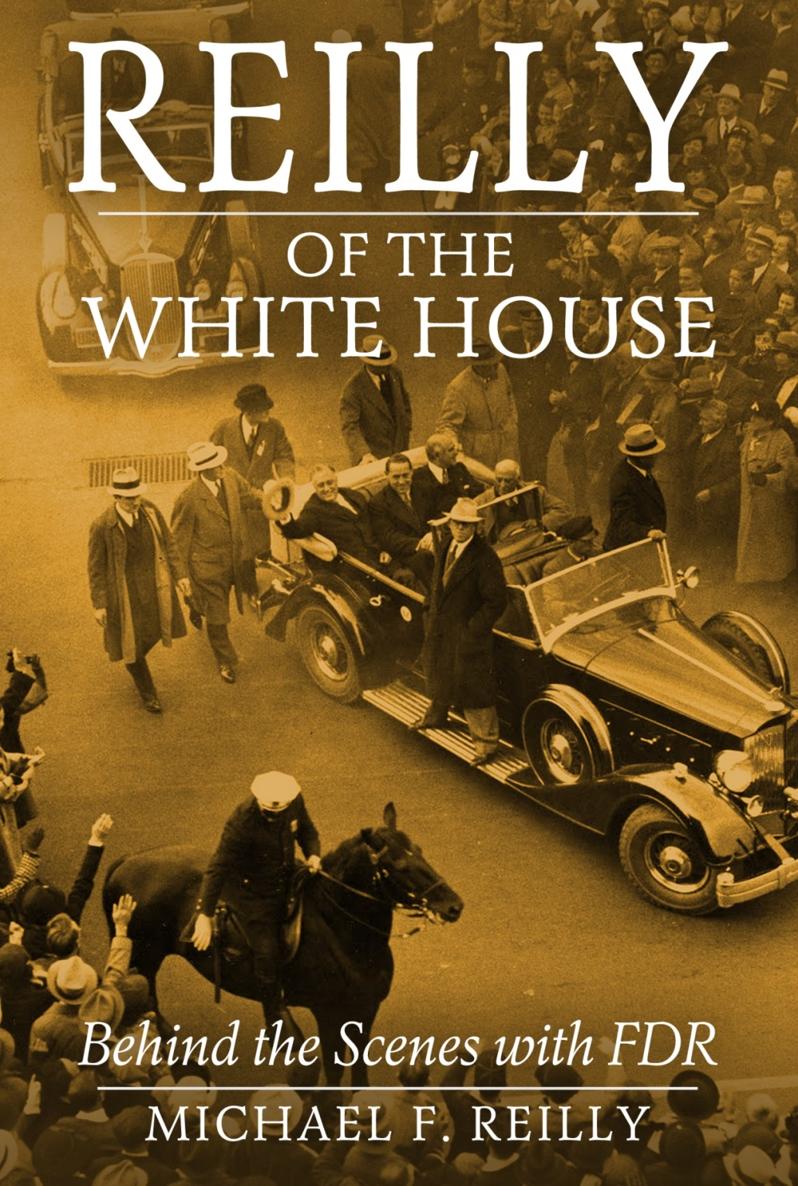

Reilly of the White House was originally published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster, Inc., New York.

ONE. A Quiet Sunday

One of the things I loved most about the White House was the way it reverted to type when given half a chance. Six days a week it was just a bustling modern office building with sleeping arrangements attached. But on the seventh day the sound and fury were gone and 1600 Pennsylvania became once again a graceful home, in the best Southern tradition. Voices were lowered, ushers walked instead of scurrying, politicians acted like guests and gentlemen.

It was on such a peaceful Sunday that I sat in Chief Usher Wilson Searles office, a cubbyhole at the main entrance to the Mansion. In the next room FDR was lunching with his Secretary of Navy, Frank Knox. Searles and I were discussing fishing, and a bored young man draped in the gaudy golden loops of a Secretary of Navys aide yawned, listened to us, and yawned some more. Searles phone rang and he answered it with, Searles, White House Ushers Office. In a moment he passed the phone on to the aide, saying, Its the Navy Department calling you. Knoxs young man took the phone. Being an old Secret Service man, I kept just a little bit of my ear open for the conversation. It was not only a rude gesture, but completely unnecessary, for the officers gold braid began to flap as he yelled into the receiver: My God, you dont mean Pearl Harbors been bombed?

The aide listened for a second and then hung up, completely missing the telephone cradle twice before he could get the instrument in place. Ive got to see the Secretary at once, he told me, and I merely pointed to the room where FDR and Knox were lunching.

The aide took off in a full gallop for the room, pulling himself up after a step to turn to me and say: Mike, please dont say anything about this.

I told him I thought it would be a pretty tough job keeping the bombing of Pearl Harbor a state secret and started telling a few people about it right away. I went to the White House switchboard and told the girl: Start calling in all the Secret Service men who are off duty. Dont tell em why, just call em in. All the White House police, too. And get me Starling, Wilson, and Morgenthau. Starling was my boss, Wilson was Starlings boss, and Morgenthau was Wilsons boss.

I dialed Ed Kelly, Washingtons Chief of Police, to tip him off and to ask him to send sixteen uniformed police over to the White House immediately and not to bother telling them why.

Colonel Ed Starling, the Chief of the Detail, had gone off for a ride in the country with his wife, a luxury he allowed himself about three times a year: Frank J. Wilson, Chief of the United States Secret Service, and proud custodian of about four gallons of one degree above freezing water in his veins, wanted to know what I was doing about things and didnt seem overly impressed by my answers; and Henry Morgenthau, the Secretary of the Treasury and the big boss of the Secret Service, screamed as though stabbed, ordered me to double the guard immediately, hung up, called back in ten seconds and ordered me to quadruple the guard and issue machine guns all around.

In the midst of my phoning the buzzer sounded, warning us that the President was on his way to his office. As he was wheeled by I had time for only a quick glimpse. His chin stuck out about two feet in front of his knees and he was the maddest Dutchman Ior anybodyever saw.

The White House began to fill with key secretaries, presidential assistants, and Secret Service men. Most of them had been summoned by telephone. The naval aides hopes for keeping the bombing of Pearl Harbor a secret disappeared as the news started leaking hysterically out of radios from coast to coast. Crowds began gathering outside the White House, but they were no problem as we had had sufficient warning to double the uniformed guard all around. It was never necessary to quadruple it, nor did we get around to issuing machine guns. However, in time we did set a couple of Army machine gun crews atop the White House and moved antiaircraft batteries into position all around it.

The White House staff was excited, but probably no more so than any normal group of competent Americans who had work to do in the midst of the shock of December 7, 1941. As members of the Detail drifted in I assigned them what I hoped were strategic posts all over the White House and its spacious grounds. Men from Secret Service District 5 (thats Washington) were put on duty, and a couple of military police detachments arrived on the double from Fort Myer, across the Potomac. We were ready for anything. That is, we were ready for anything if we had the slightest idea of what to expect.

The White House correspondents, my friends of many gay and carefree off-duty hours, started filling the press room. Immediately we resumed our normal working hour relationship of arch-enemies. No longer gay companions, they were beady-eyed ferrets, gifted to a man with a second sense and Supermans X-ray eyes. Gently and suavely, I hope, I kept them in their smoke-filled pen, while they solicitously questioned me concerning a couple of hangovers about which I possessed rather painful personal knowledge. I assured them I was feeling quite well, thank you, and that I didnt know anything that they didnt know. About then the Presidents very canny press secretary, Steve Early, stepped fearlessly into the middle of the cage, and in no time the roaring beasts were quiet.

Morgenthau arrived and had me run through all the protective measures I had instituted. As I reeled them off the Secretary kept peering through the White House windows in search of enemy aircraft. I must admit his fears are considerably more amusing now than they were on December 7.

On December 8, Frank Wilson called me to his office and told me that Morgenthau had just signed an order promoting me from Assistant Supervising Secret Service Agent at the White House to Supervising Agent. It was felt that my youth and six years experience with the President would make for better leadership than the elderly Colonel Starling could provide. That was a flattering opinion which I did not share, and I am afraid there were a few harsh words between Wilson and Reilly. I proposed that Starling, always a fair and honest boss, should remain as co-Supervising Agent. I wanted his advice and help. Wilson doubted that the Colonel would accept that arrangement. I said I thought I could take care of that, and I did. At first Starling, deeply and justifiably hurt, would have no part of the deal, but I finally talked him into it. He stayed with me for eighteen months, until his health forced his retirement in 1943, and he was always a completely reliable source of aid and comfort to an Irishman who sometimes had more muscle than brain. Starling and I had never been anything but business acquaintances, so I must always feel very sentimental and grateful about the old gent.