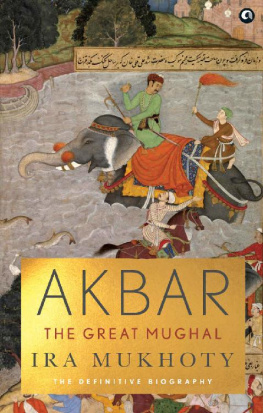

THE EMPEROR AKBAR

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I

Table of Contents

T HE A RGUMENT

I crave the indulgence of the reader whilst I explain as briefly as possible the plan upon which I have written this short life of the great sovereign who firmly established the Mughal dynasty in India.1

1 For the purposes of this sketch I have referred to the following authorities: Memoirs of Bbar, written by himself, and translated by Leyden and Erskine; Erskine's Bbar and Humyn;The Ain--Akbar (Blochmann's translation); The History of India, as told by its own Historians, edited from the posthumous papers of Sir H. M. Elliot, K.C.B., by Professor Dowson; Dow's Ferishta; Elphinstone's History of India; Tod's Annals of Rajast'han, and various other works.

The original conception of such an empire was not Akbar's own. His grandfather, Bbar, had conquered a great portion of India, but during the five years which elapsed between the conquest and his death, Bbar enjoyed but few opportunities of donning the robe of the administrator. By the rivals whom he had overthrown and by the children of the soil, Bbar was alike regarded as a conqueror, and as nothing more. A man of remarkable ability, who had spent all his life in arms, he was really an adventurer, though a brilliant adventurer, who, soaring above his contemporaries in genius, taught in the rough school of adversity, had beheld from his eyrie at Kbul the distracted condition of fertile Hindustn, and had dashed down upon her plains with a force that was irresistible. Such was Bbar, a man greatly in advance of his age, generous, affectionate, lofty in his views, yet, in his connection with Hindustn, but little more than a conqueror. He had no time to think of any other system of administration than the system with which he had been familiar all his life, and which had been the system introduced by his Afghn predecessors into India, the system of governing by means of large camps, each commanded by a general devoted to himself, and each occupying a central position in a province. It is a question whether the central idea of Bbar's policy was not the creation of an empire in Central Asia rather than of an empire in India.

Into this system the welfare of the children of the soil did not enter. Possibly, if Bbar had lived, and had lived in the enjoyment of his great abilities, he might have come to see, as his grandson saw, that such a system was practically unsound; that it was wanting in the great principle of cohesion, of uniting the interests of the conquering and the conquered; that it secured no attachment, and conciliated no prejudices; that it remained, without roots, exposed to all the storms of fortune. We, who know Bbar by his memoirs, in which he unfolds the secrets of his heart, confesses all his faults, and details all his ambitions, may think that he might have done this if he had had the opportunity. But the opportunity was denied to him. The time between the first battle of Pnpat, which gave him the north-western provinces of India, and his death, was too short to allow him to think of much more than the securing of his conquests, and the adding to them of additional provinces. He entered India a conqueror. He remained a conqueror, and nothing more, during the five years he ruled at Agra.

His son, Humyn, was not qualified by nature to perform the task which Bbar had been obliged to neglect. His character, flighty and unstable, and his abilities, wanting in the constructive faculty, alike unfitted him for the duty. He ruled eight years in India without contributing a single stone to the foundation of an empire that was to remain. When, at the end of that period, his empire fell, as had fallen the kingdoms of his Afghn predecessors, and from the same cause, the absence of any roots in the soil, the result of a single defeat in the field, he lost at one blow all that Bbar had gained south of the Indus. India disappeared, apparently for ever, from the grasp of the Mughal.

The son of Bbar had succumbed to an abler general, and that abler general had at once completely supplanted him. Fortunately for the Mughal, more fortunately still for the people of India, that abler general, though a man of great ability, had inherited views not differing in any one degree from those of the Afghn chiefs who had preceded him in the art of establishing a dynasty. The conciliation of the millions of Hindustn did not enter into his system. He, too, was content to govern by camps located in the districts he had conquered. The consequence was that when he died other men rose to compete for the empire. The confusion rose in the course of a few years to such a height, that in 1554, just fourteen years after he had fled from the field of Kanauj, Humyn recrossed the Indus, and recovered Northern India. He was still young, but still as incapable of founding a stable empire as when he succeeded his father.

He left behind him writings which prove that, had his life been spared, he would still have tried to govern on the old plan which had broken in the hands of so many conquerors who had gone before him, and in his own. Just before his death he drew up a system for the administration of India. It was the old system of separate camps in a fixed centre, each independent of the other, but all supervised by the Emperor. It was an excellent plan, doubtless, for securing conquered provinces, but it was absolutely deficient in any scheme for welding the several provinces and their people into one harmonious whole.

The accident which deprived Humyn of his life before the second battle of Pnpat had bestowed upon the young Akbar, then a boy of fourteen, the succession to the empire of Bbar, was, then, in every sense, fortunate for Hindustn. Humyn, during his long absence, his many years of striving with fortune, had learnt nothing and had forgotten nothing. The boy who succeeded him, and who, although of tender years, had already had as many adventures, had seen as many vicissitudes of fortune, as would fill the life of an ordinary man, was untried. He had indeed by his side a man who was esteemed the greatest general of that period, but whose mode of governing had been formed in the rough school of the father of his pupil. This boy, however, possessed, amid other great talents, the genius of construction. During the few years that he allowed his famous general to govern in his name, he pondered deeply over the causes which had rendered evanescent all the preceding dynasties, which had prevented them from taking root in the soil. When he had matured his plans, he took the government into his own hands, and founded a dynasty which flourished so long as it adhered to his system, and which began to decay only when it departed from one of its main principles, the principle of toleration and conciliation.

I trust that in the preceding summary I have made it clear to the reader that whilst, in a certain sense, Bbar was the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India, he transmitted to his successor only the idea of the mere conqueror. Certainly Humyn inherited only that idea, and associating it with no other, lost what his father had won. It is true that he ultimately regained a portion of it, but still as a mere conqueror. It was the grandson who struck into the soil the roots which took a firm hold of it, sprung up, and bore rich and abundant fruit in the happiness and contentment of the conquered races.