Kellow Chesney - The Victorian Underworld

Here you can read online Kellow Chesney - The Victorian Underworld full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Victorian Underworld

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Victorian Underworld: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Victorian Underworld" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Victorian Underworld — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Victorian Underworld" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To define the exact extent of the mid-century underworld would be an impossible task. It had no sharp boundaries but everywhere blurred off into the society around it, and though it was intimately related to poverty and crime its limits cannot be fixed simply in those terms. The miserable west country labourer, half dependent on stolen turnips and poached rabbits, no more belongs than the titled banker jailed for embezzlement; while the Haymarket night-house keeper, rich with earnings the law allowed, qualifies as unquestionably as the pickpocket and the footpad. Yet for all its indefiniteness this underworld remains a clearly recognizable part of the civilization that produced itand whose character and values it continually affected.

When respectable people spoke of the dangerous classesa phrase enjoying a good deal of currencythey were not talking about the labouring population as a whole, nor the growing industrial proletariat. Neither were they referring to that minority of politically conscious, mostly 'superior' radical working men on whom any sustained working-class political movement ultimately depended. They meant certain classes of people whose very manner of living seemed a challenge to ordered society and the tissue of laws, moralities and taboos holding it together. These 'unprincipled', 'ruffianly', 'degraded' elements seemed ready to exploit any breakdown in the established order. They aroused a natural anxiety among a ruling class conscious of the strains to which rapid economic change was subjecting the whole social organism.

The thieves, cheats, bullies, beggars, touts and tarts with whom this book is chiefly concerned all belonged, more or less, to the dangerous classes. These classes, however, were not limited to professional parasites and delinquentsif they had been they would hardly have seemed such a danger to the established order. What was disturbing was that they included thousands who not only earned a legitimate living when they could, but earned it in ways vital to the prosperity of the society whose stability they seemed to threaten. Among port labourers and street traders, in sections of the iron-working and construction industries, were people cut off from the accepted patterns of civilized life: among a good many of them even so fundamental an institution as legal marriage was in general disuse. Society had made itself dependent on a large community of men and women who were estranged from it and hostile to its canons; men and women with no fixed homes or steady livelihood, who looked on the domesticated and respectable with, at best, watchful half-predatory eyes. In trying to come to terms with a subject matter that defies firm definition it may be worth while to examine some of these groupsthe semi-barbarous tribes whose social territories formed, as it were, the marches of the underworld.

Nothing in the Victorian era compared for social impact with the coming of the railways. In two decades a net of what quickly became arterial lines was flung over the land, bringing such transformations that it quickly became difficult to conceive life without it. The elaborate system of cuttings and embankments, bridgings and borings was created, like the pyramids, by concentrations of human muscle. As the creeping railheads drew their trails across the countryside they carried with them armies of navvies and their camp followers.

As their name (land 'navigators' or canal builders) indicates, the navvies were not newcomers to the English scene. For many years villages near canal workings had seen young men go off with the navigator gangs, as lost to home and friends as those who took the Kings shilling. Over the years there had grown up a caste of specialized nomad labourers with their own habits and traditions; and although the railway boom vastly increased their numbers and spread them to every region of the country, it did not destroythough it perhaps began to underminetheir sense of being a race apart. Moreover the huge forces of them now recruited (and not only for railway building) enabled the steam-age navvies to be as much a law to their truculent selves as their eighteenth-century predecessors.

The navvies' manners were rough. One engineer told an official inquiry in 1846 that it was dangerous to approach them when they were not actually at work 'if they were in crowds or at all disposed to be unruly'. Even the contractors and gang bosses, most of whom were exceptionally tough, were often afraid to venture into their encampments.

As for the inhabitants of districts where large-scale works were in hand, they were apt to find themselves living under a sporadic reign of terror, only made supportable by the long hours railway navvies worked. Quiet villages, where the law was represented by a part-time parish constable, would be invaded by a horde of brawny, insolent men in strapped velveteens and spotted neckcloths, inclined to spend their leisure lounging about the lanes, throwing stones at passers, accosting local women, taunting their menfolk and generally spoiling for trouble. On the evening of a Saturday pay-day scenes of wild disorder were likely to break out round the local inns. Ready to bait and ill-treat outsiders, navvies were also given to ferocious fights among themselves, on which they betted freely.

They were not respecters of persons and as willing to stone a lady's carriage as a country cart. Cottagers, farmers and landowners all suffered, for navvies would pillage orchards and hen-roosts like an army of occupation, and they were ardent poachers. Gamekeepers could not hope to withstand their onslaughts, and landed proprietors (among many of whom game preserving was almost a religion) had to watch while not only fields and coverts but the very park under their windows was denuded of hares and pheasants.

It was not only rural parishes that felt the weight of the navvy's hand. Of an evening, when work on a near-by railroad was over for the day, chance passers through a country town might find the place apparently deserted by all respectable citizens; they had retired indoors leaving the streets to the navvies and their hangers-on. In fact, where they were in strength, the railway navvies seem to have held local authorities in contempt. As a perhaps over emphatic witness explained to the 1846 Committee, 'From being long known to each other they generally act in concert, and put at defiance any local constabulary force; consequently crimes of the most atrocious character are common, and robbery without attempt at concealment an everyday occurrence/

But there were compensations. Experienced, fully able navigators might get about twice the current wage of ordinary labourers and, since they were notoriously free spenders, they were not altogether unwelcome to butchers, bakers and brewers. They crammed themselves into cottages, barns, cellars and any other lodging they could find, and for all their destructiveness were likely to be profitable tenants. Where no billets were to be found they simply made bivouacs with whatever materials lay to hand, so that anarchic and insanitary encampments grew up. In the west country there were places where lines of rough and squalid lean-to's followed the high field-banks. When, as happened especially in the north, a railway had to be driven across miles of remote fell and moorland, townships of crude bothies sprang up.

Some slept in huts constructed of damp turf, cut from the wet grass, too low to stand upright in, while small sticks covered with straw served as rafters.... Others formed a room of stones without mortar, placed thatch or flags across the roof, and took possession of it with their families, often making it a source of profit by lodging as many of their fellow workmen as they could crowd into it.... In these huts they lived; with man, woman and child mixing in promiscuous guilt; with no possible separation of the sexes; in summer wasted by unwholesome heats, and in winter literally hewing their way to work through the snow. In such places from nine to fifteen hundred were crowded for six years. Living like brutes, they were depraved, degraded and reckless. Drunkenness and dissolution of morals prevailed. There were many women but few wives; loathsome forms of disease were universal. Work often went on on Sundays as well as other days.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

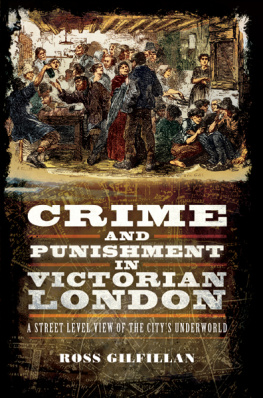

Similar books «The Victorian Underworld»

Look at similar books to The Victorian Underworld. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Victorian Underworld and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.