Ah! my poor dear child, the truth is, that in London it is always a sickly season. Nobody is healthy in London, nobody can be.

Jane Austen, 1816 Emma

J AMES PARKINSON was born into the Enlightenment on Friday 11 April 1755. He grew up alongside the Industrial Revolution and died a Romantic on Tuesday 21 December, 1824. His life spanned a period of intellectual turbulence and political upheaval, burgeoning science and technology; they were dramatic and exciting times to be alive. Among his contemporaries were Mozart and Marie Antoinette, the chemists Joseph Priestley and Humphry Davy, the surgeon brothers John and William Hunter, Edward Jenner who discovered the smallpox vaccine, the poet William Wordsworth, the painter William Turner, and the geologist William Smith.

James was the second of six children, As people were generally buried less than a week after their death, it seems likely that Mary actually died a few days short of her 90th birthday.

Attempts to determine the birthdate and birthplace of Parkinsons father, John, have met with less success. Furthermore, there is no record of any marriage between a John Parkinson and a Mary Sedgwick (or indeed any Mary at all) between 1750 and 1753 the most likely period for a marriage to have taken place, given the arrival of the couples first child in November 1753.

Nor has any portrait of James Parkinson yet been found, although the internet boasts two different photos supposed to be of him. Unfortunately, since photography was not invented until 1838, fourteen years after Parkinson died, a photograph of him cannot possibly exist. The photographs in question are of two different James Parkinsons. One was a dentist who lived 18151895. The image of him was clipped from a group photo taken in 1872 of the membership of the British Dental Association. The man in the other photo, who has a big bushy beard, is a James Cumine Parkinson (1832-1887), an itinerant Irishmen who ended up as a lighthouse keeper off the coast of Tasmania.

We are therefore left to imagine Parkinsons physical appearance, and to help us do that we have a brief verbal description written by his young friend, Gideon Mantell. Like Parkinson, Mantell was a medical practitioner with a passion for fossils.

Another man with whom our James Parkinson is often confused was an older James Parkinson (1730-1813) whose wife purchased the winning lottery ticket for the disposal of Sir Ashton Levers exotic natural history collection. Noted for the artefacts it contained from the voyages of Captain Cook, formation of the collection had bankrupted Lever. In order to recover some of the money he obtained an Act of Parliament which allowed him to sell the collection by lottery, but at a guinea each he only sold 8,000 tickets, when he had hoped to sell 36,000. The lucky James Parkinson who acquired the collection spent nearly two decades trying to make a success of Levers museum, eventually putting it up for auction in 1806. Our James Parkinson was present at the auction and purchased a number of items.

The James Parkinson with whom this book is concerned lived all his life in Hoxton, a village located a mile north of Bishopsgate, one of the narrow medieval gates of the City of London, across from north to south, and five miles east to west, which is larger than the whole of London was in 1750.

As the city became more and more prosperous during the eighteenth century this was reflected in Hoxton where the population grew rapidly. There was a phenomenal rise in trade in the docks and in business generally, which fed an increase in employment and attracted agricultural workers out of the fields and into the metropolis. Residential areas in the city were taken over for business purposes, and as houses were demolished to make room for factories, warehouses and offices, displaced residents and incomers were forced to find homes beyond the City walls in places like Hoxton. The City Fathers, wealthy merchants and businessmen who could afford a horse and carriage, were able to live where they chose and opted for country seats or sophisticated squares. Oh how I long to be transported to the dear regions of Grosvenor Square! sighs Miss Sterling in George Colmans popular comedy The Clandestine Marriage. Such Georgian squares launched a new style of town-house: the narrow-fronted terrace; and vertical living became both a novelty and a necessity as space became scarce and land more expensive. Terraces were often set around a square to compensate for the fact that the houses themselves had little land of their own.

The Parkinsons lived at No. 1 Hoxton Square, a three-storey terraced town house constructed between 1683 and 1720 around a large square of more than half an acre. However, a badly deteriorating plaque dedicated to the memory of his father, John Parkinson, can still be seen on the churchyard wall. John had been the much-loved apothecary surgeon in Hoxton for more than 40 years, fulfilling a position in society similar to that of todays GP. The twelve-line inscription probably once told us who had erected the plaque and why, but it is now illegible. Another plaque inside the church, put up in 1955, celebrates the bicentenary of James Parkinsons birth.

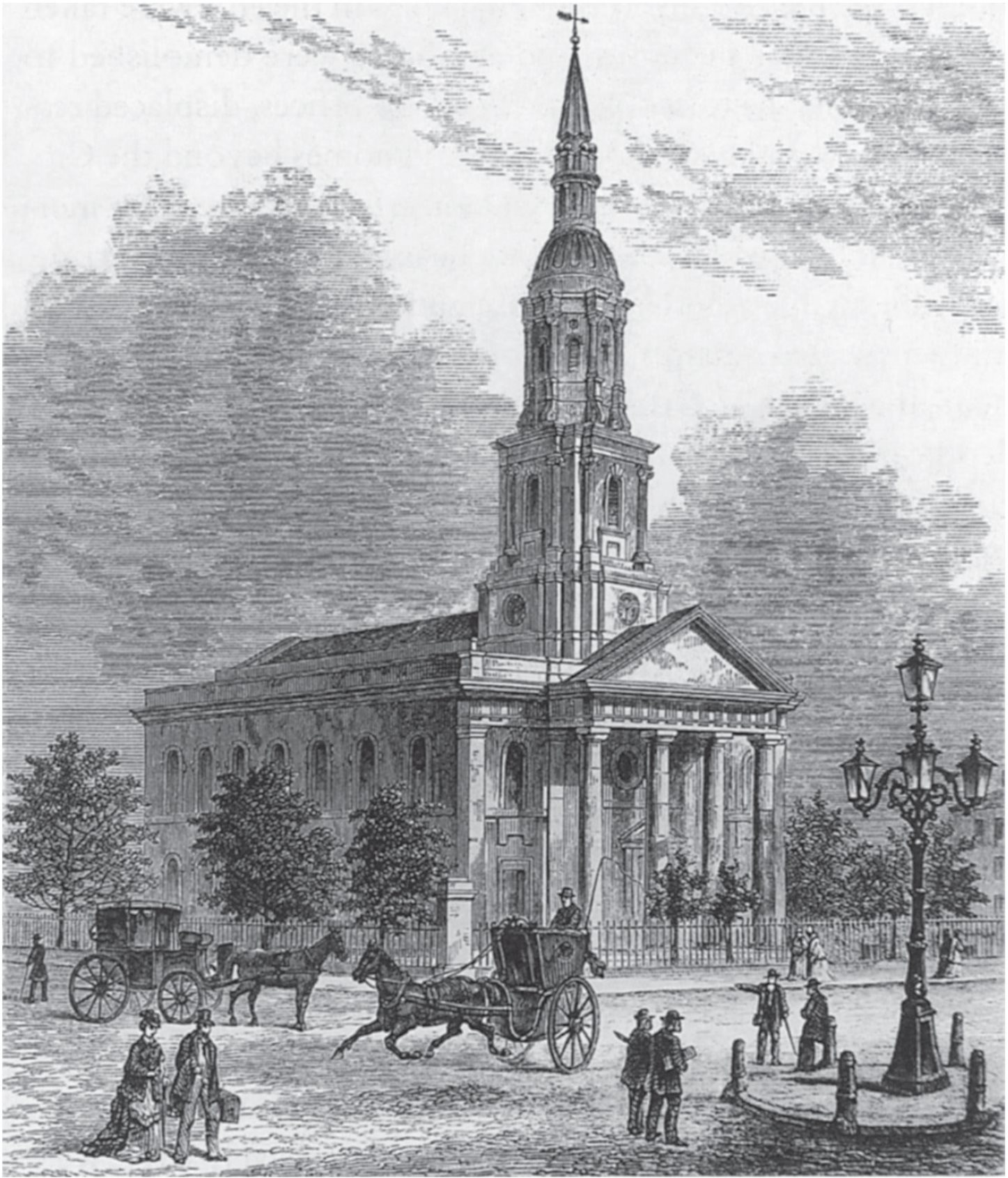

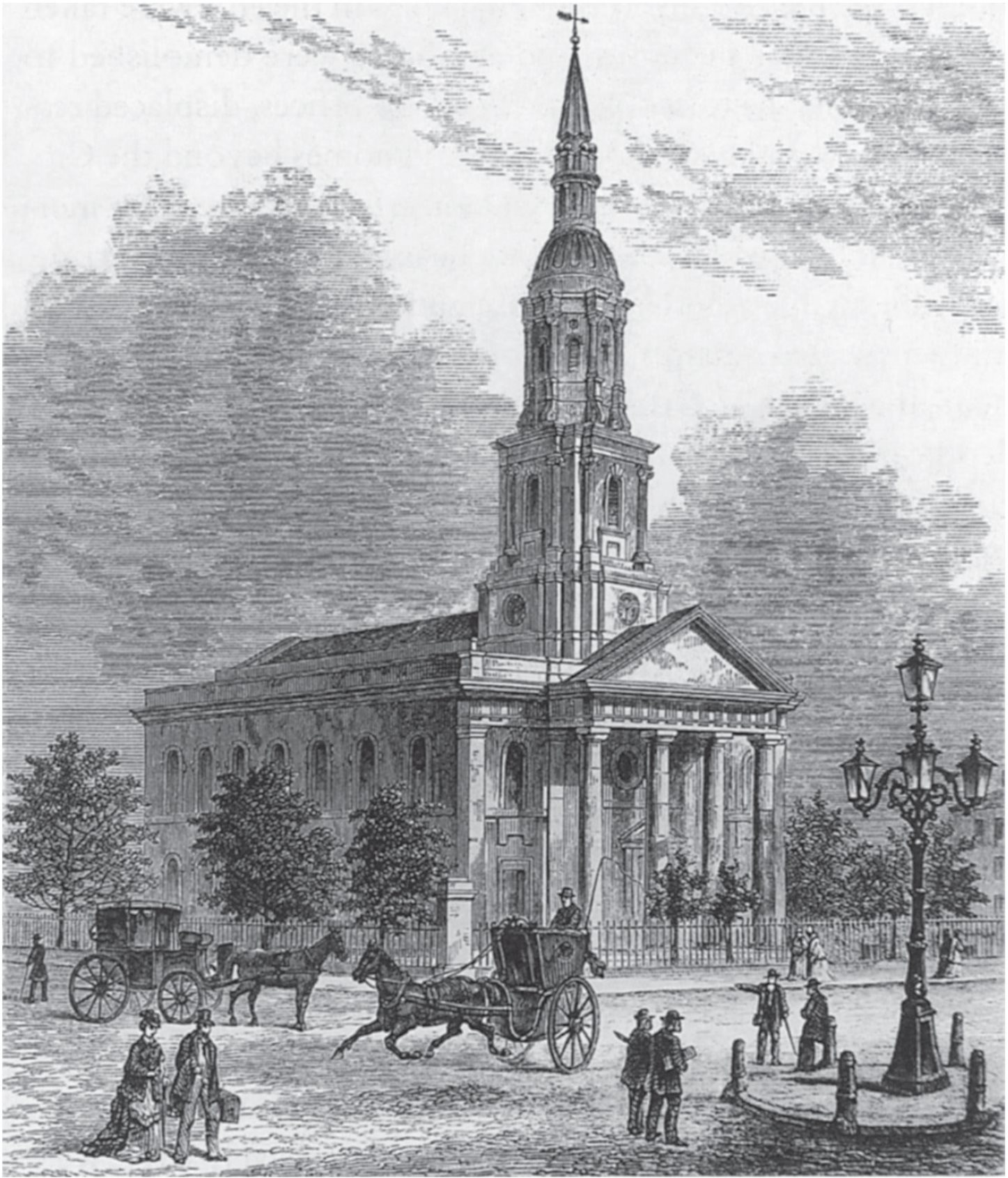

St Leonards Church, Shoreditch, as James Parkinson would have known it.

The original house at No. 1 Hoxton Square was still standing 100 years ago, although by then it was derelict. At that time it had a smaller two-storey building on the back with a central door that opened on to a side street. This door had probably been the entrance to the apothecary shop where the Parkinsons made up and dispensed medications. Behind that was yet another small building which may have been added at a later date to house Parkinsons ever-growing collection of fossils. Side streets provided access to shops and services, but beyond these, when James was born in 1755, were open fields, market and flower gardens, orchards, and grand old mansions standing in extensive grounds.

Despite the apparent grandeur of Hoxton Square, sanitary conditions were appalling. Household waste fed into open ditches that flowed down the centre of the streets, since Hoxton had no sewer. The ditches discharged into a tributary of the Walbrook river that ran through Shoreditch; the Walbrook, now one of Londons several subterranean rivers, eventually released Hoxtons waste into the heavily polluted Thames. At night there would be commodes in the bedrooms, while in most dining rooms there was a set of chamber pots hidden behind curtains or in a cupboard for the relief of gentlemen after dinner. These were generally emptied straight into the street, although one of the greatest causes of pollution of Londons waterways occurred with the introduction of the improved water-closet in the 1770s. Many of these overhung streams the earliest and simplest way of disposing of the contents. The house itself probably had piped water, drawn from the Thames and supplied via pipes of elm wood laid under the main streets, although the source of that water was highly questionable and the contents virtually undrinkable, as one Scottish visitor lamented:

If I would drink water, I must quaff the mawkish contents of an open aqueduct, exposed to all manner of defilement; or swallow that which comes from the river Thames, impregnated with all the filth of London and Westminster human excrement is the least offensive part.

Next page