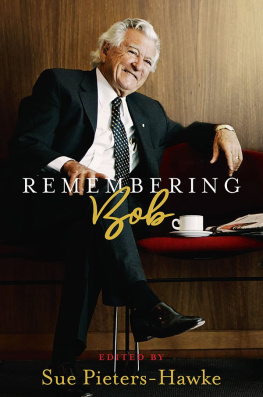

First published in 2019

Copyright in the collection Sue Pieters-Hawke 2019

Copyright in the individual pieces with their authors

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publisher at the address below.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 739 6

eISBN 978 1 76087 278 6

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

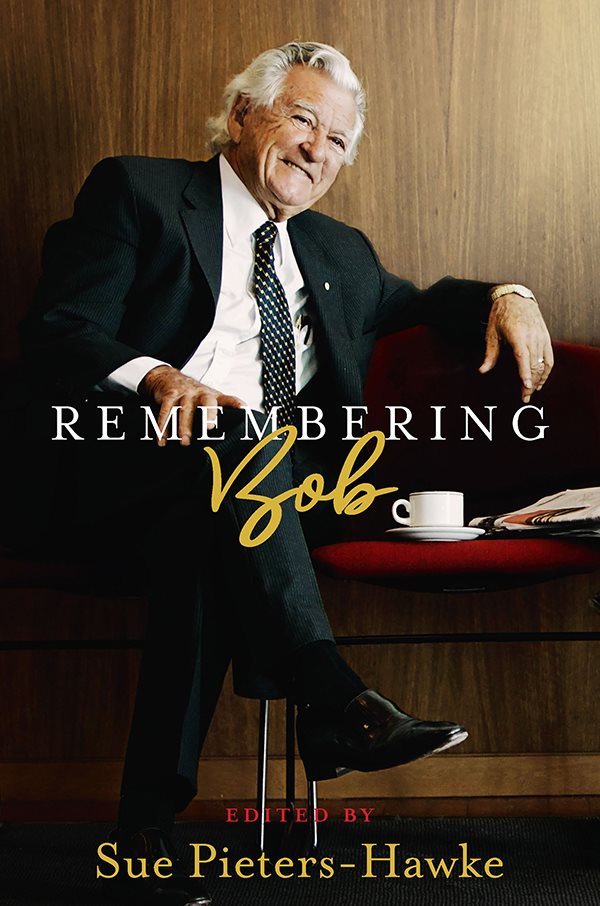

Cover design: Deborah Parry

Front cover photograph: Courtesy of Sydney Morning Herald

The essence of power is the knowledge that what you do is going to have an effect, not just an immediate but perhaps a lifelong effect, on the happiness and wellbeing of millions of people, and so I think the essence of power is to be conscious of what it can mean for others.

Bob Hawke

THIS IS NOT going to be a dull book! Hawke was a vivid fellow, and entertaining by his very nature. His very contradictions made him so. A Congregationalist ministers son who revelled in the profane Australian tongue. From a Temperance tradition he seemed bent on letting abstainers know what they were missing out on, until in the interests of the polity of the Commonwealth he himself renounced liquor. A Rhodes Scholar whose weekend Bible was the racing guide and who spoke in the most energetic Australian demotic. The face that launched many a strike, but from whose lips came the words of Accord. The man who opened Australia to the world and wanted to maintain, as an essential mark of our society, the Social Wage. In speaking of such things, he had some of the marks of a prophet. He blazed with certainties. And when his lips formed that potent rictus of denunciation, everyone around, particularly journalists he considered snide, went pale. For his eyes could flash with a hawkish savagery.

I dont need to say: he wasnt perfect. Everyone knew it, for he admitted to his flaws on television. As well, he changed uranium policy to help a Labor South Australian government, and he let the Western Australian Premier Brian Burke chase him away from creating Commonwealth-wide land rights law. He might have had a weakness for the spivs of the 1980s, but at the apogee of the new Australian capitalism, the winning of the Americas Cup, he sat in his bodgie jacket and famously invoked the proposition that workers were entitled to take their leisure too.

By his own admission a less than model husband, he nonetheless recognised the competence of women and the authenticity of womens voices, and appointed Susan Ryan to the position of Minister Assisting on the Status of Women. I could go on for thousands of words about Hawkies contradictions. He wore his paradoxes boldly and with an unrehearsed exuberance that captured the peoples imagination and affection in a way no subsequent PM has done. There was no formula to it. It was just Hawkie!

Anyone, any citizen who ever spoke to him, was astounded by the way he stopped, fixed his gaze on you, andunless you were an utter fascist screamerseemed absorbed by your observations. This always appeared to be a huge gift of attention, an electoral compliment to the voter. And he did it because he saw us as more than mere integers in an economy, and more than mere clients of the state. He convinced those to whom he spoke that they figured as an inheritor of a special and utopian society, and he was emphatic that that special society had not been reduced to a mere market, just because we had entered the global market. Thus, his demeanour grew out of his convictions about the Commonwealth, beliefs bred in him by a strong mother and a kindly father, members of a church that emphasised Christs social statements; and, after his motor bike accident when he was seventeen, the same year his brother Neil died, reinforced by the influence of the Labor Party. In the Australia of his boyhood, there was a sense that though we lived in the back-blocks of the world, we had the dignity of belonging to a society that would never abandon its children.

Hawke was scorned when in 1987 he declared that by 1990 no Australian child would be living in poverty. His speech notes on the day he made this pledge said: No Australian child need live in poverty. In any case, neo-conservatives had conniptions at the whole concept. The market, the great God and Moloch of the modern age, decreed who was poor, who wasnt. The poor were leaners, not lifters. Modern market economics came near to confirming the nineteenth century Tory concept that poverty could be blamed on the poor themselves.

What was wrong with such a hope, prayer, aspiration? It is an aspiration negated by the tendency of recent governments to limit the commitments between the state and the people, to wave a big stick at unemployed and the aged. I prefer Hawkes vision.

Hawkie really got the arts. He saw every Australian film that gained the worlds attention, every book, every work of art, every song performed, as part of a great communal enterprise. Hawke escaped the limits of our post-colonial mind. The urgency to get out there ourselves and be actors in our own stories has diminished since Hawkes era.

My own stories of Hawkie?

I remember a night in the late 1970s when, at a party in the Rose Garden of Old Parliament House, he complained to a press baron whose newspaper had been condemnatory of his union activismhe said the baron was proving to be a geriatric fuckwit. There are no such voices raised in precisely those terms to press barons now, and we are the poorer for it.

How do you like your tipster? he shouted with that Hawke exuberance once at the Sydney Football Stadium after the team he had unfashionably predicted as victors won a Rugby League Grand Final.

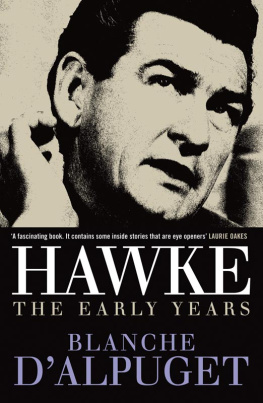

One afternoon when Hazel Hawke called me in to Kirribilli House to discuss writing a book, Hawke sat by in tracksuit and with the racing guide, half-listening, and suddenly it was like visiting any couple who were getting on a bit. And I must record the two women of his life! Hazel, the great, enduring pilgrim in her own right, has left her children and grandchildren a legacy of amiability, intelligence and adaptability. And then Blanche DAlpuget, gifted writer, whose work on Hawke is the best political biography written in Australian history. Blanche had, despite her notable literary talent, all the disadvantages of beauty, particularly the popular suspicion that the beautiful are shallow. I was always fascinated by her interest in monasticism and similar mattersI remember receiving from her a bottle of chutney, a gift she bought during a time of reflection in a Benedictine monastery. Both of these women were and are remarkable in their own right. I salute them for taking on and adjusting their lives to the meteor that was Hawke.