The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, founded at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, who went on to become the thirty-first president of the United States, is an interdisciplinary research center for advanced study on domestic and international affairs. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

www.hoover.org

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 495

Copyright 2002 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

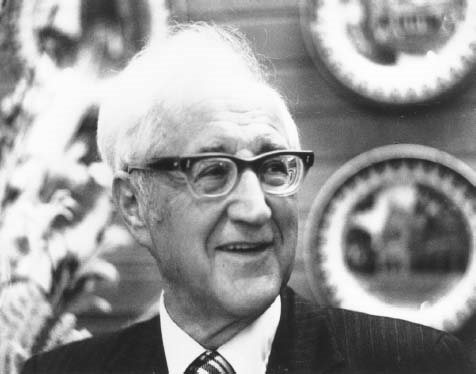

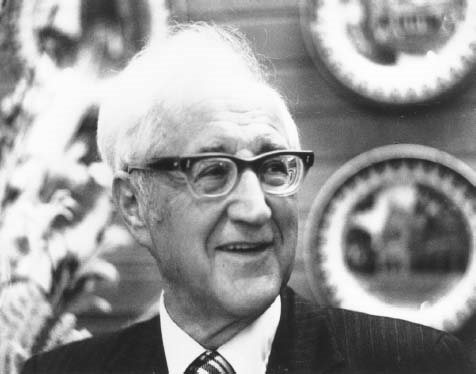

Photographs on cover and frontispiece are reproduced courtesy of the Hoover Institution Archives.

First printing 2002

08 07 06 05 04 03 02 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stallones, Jared.

Paul Robert Hanna : a life of expanding communities / Jared R. Stallones.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-8179-2832-4 (alk. paper)

1. Hanna, Paul Robert, 190288 2. EducatorsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Title.

LB875 .H222 S72 2002

370.92dc21

[B]

2001039664

To Jan, Lindsay, and Cameron for all their sacrifices

Contents

Index

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the help and guidance of Dr. O. L. Davis Jr., Dr. Eugene L. Johnson, Dr. David B. Gracy III, Dr. Mary S. Black, and Dr. Norman Brown. Their encouragement and advice are deeply appreciated. The cooperation of Mrs. Aurelia Hanna and John P. Hanna was also invaluable. Their willingness to share their family stories of Paul Hanna added depth to my understanding of him. Thanks to all of Paul Hannas former students and colleagues who spent time helping me understand the complexities of this educational leader. Many thanks to Gerald Dorfman, curator of the Hanna Collection, for all of his encouragement and kindness. A special debt of gratitude is owed to Don, Sharla, David, and Zachary Ekvall, who gave of their time to allow me the freedom to complete this book. Finally, this project would not have been possible without the support of John Raisian, director of the Hoover Institution.

1

Introduction

S ocial studies education plays a crucial role in preparing American children to take on the duties of citizenship. In a liberal democracy, however, tensions exist between the needs of individuals and those of the greater society. These tensions are evident in public education every time a teacher encounters difficulty interesting students in the prescribed curriculum. Paul Robert Hanna struggled throughout his career with these often conflicting needs as he sought an appropriate balance for the foundation of social education in the schools. The models he developed went far beyond the traditional approaches to the social studies.

Hannas solution, first reached in the 1930s and refined in many applications throughout the remainder of his career, replaced the traditional approach to American schools social studies programs in the elementary grades with a new curriculum design. Instead of deferring until the upper elementary grades a thoughtful introduction to several social sciences, or offering only history and geography as discrete subjects, Hanna incorporated Harold Ruggs integrated secondary social studies approach in his design for the elementary social studies curriculum. Hanna believed that the social sciences could be employed to help students understand the development of the social, political, and economic systems in which they lived. Deeper understanding would empower them to effect change through democratic means that would benefit them as individuals and society as a whole.

Hannas work took many forms, from educational research and consultations with schools and governments here and abroad to helping establish professional organizations as forums for discussion of the role of education in society. His consistent focus throughout his career, however, was development and refinement of the expanding communities design for elementary school social studies instruction. Promulgated in several major textbook series published by Scott, Foresman and Company for almost forty years, the expanding communities design profoundly changed how social studies was taught in schools both in the United States and abroad.

Surprisingly, given his long career and major contributions to education, no comprehensive biography of Hanna exists, although three dissertations have focused on aspects of his work. Robert E. Newman Jr. (1961) studied Building America, a monthly magazine series designed to help secondary students investigate social problems facing the United States. Hanna proposed this series to the Society for Curriculum Study and chaired its editorial board from the magazines inception in 1935 to its demise in 1948. At its peak, Building America enjoyed a monthly circulation of more than a million copies. Norman Miller (1967) focused on the way in which Hannas expanding communities curriculum design treated one international community, the Atlantic nations. Martin Gill (1974) focused on Hannas long and successful partnership with the textbook publishing house of Scott, Foresman and Company. Through Hannas social studies textbook series, published in multiple editions by Scott, Foresman, his expanding communities design achieved its widest dissemination and revolutionized the way social studies was taught at the elementary level. Daniel Tanner estimated that Hannas textbooks were among the most widely used in U.S. schools (1991, 43).

Despite Hannas impressive impact on American educators, professional historians of education have ignored him. David Tyack (1974), for example, did not mention Hanna in his landmark work on American schooling, even though he surely was aware of Hannas work because they were colleagues for a time at Stanford University. Herbert Kliebard (1986) also failed to include Hanna in his discussion of the Depression-era shift in progressive education from a child-centered to a social reconstructionist approach to the school curriculum. Kliebard ignored Hanna in his discussion of the Virginia Curriculum Studys role in this shift, even though Hanna was directly involved in that landmark work. Lawrence Cremin overlooked Hannas contributions in both his history of Teachers College (1954), where Hanna studied and taught for eleven years, and his study of American schooling in this century (1961). More recently, Tanner and Tanner (1990) continued this pattern of neglect. Even books on the elementary curriculum, wherein Hanna reasonably might be emphasized, routinely ignore his role. For example, one recent work described the rationale for an integrated approach to the social studies this way:

The integration of information gives students and teachers an opportunity to plan a program in which the barriers between areas of study begin to dissolve and the possibilities for experiencing real-life situations are greatly increased societal conditions are explained not only in greater depth but in a context that is meaningful in relation to contemporary living (Reinhartz and Beach 1997, 275).

Next page