First published in 1966 by Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1966 Erich Eyck

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-48265-4 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-351-05698-4 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-48114-5 (Volume 1) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-351-06087-5 (Volume 1) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

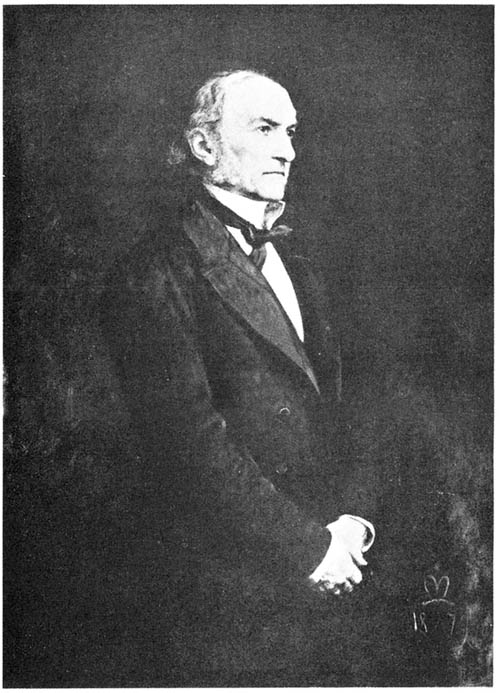

[By permission of the National Gallery

WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE

After the portrait by Sir J. E. Millais

GLADSTONE

ERICH EYCK

Translated by

BERNARD MIALL

1. A Man is Uprisen

It was the 17th of May, 1831, at Oxford. In the Union, that nursery of English politicians, in which the undergraduates debate and vote upon their motions in accordance with the procedure of the House of Commons, there was forgathered an unusually numerous assembly of young men in a fighting mood. Electoral reform was the order of the day; the very question on whose account Parliament had just been dissolved after an embittered contest. These were stirring times; for only last July, in France, a king who was the last monarch of an ancient dynasty was tumbled off the throne, and the propertied bourgeoisie seized the reins of government, led by a new king, himself a bourgeois heart and soul. The incident did not leave England unmoved, and the electors, who constituted only a thin stratum of the nation, were sufficiently alive to the spirit of the new age to send to Westminster, in the elections of the previous autumn, an unprecedented majority of progressively-minded members, all in favour of reform. And now the new Ministers of the Whig Government, although they were predominantly members of the oldest and most aristocratic familieslike Earl Grey, the Prime Minister, and the ruthless little Lord John Russellhad the courage to introduce a Reform Bill which proposed to abolish, with startling thoroughness, the abuses which had slowly come into being through the centuries, and had been so affectionately cherished, and to transfer the political power which had hitherto lain in the hands of the landed nobility and gentry to the merchants, manufacturers, and bankers of the cities which had been increasing in prosperity and importance. True, the Lords had opposed the measure, but in order to overcome their opposition the Ministers, with the support of King William IV, had appealed to the people.

Could Oxford quietly look on while such things were done? Oxford, the great guardian of the tradition that gave to her colleges, dating from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, their incomparable and indelible character; Oxford, the stronghold of the pure doctrine of the Anglican Church, which had just deprived the Conservative leader, Sir Robert Peel, of his mandate, because he had carried Catholic Emancipation; the rallying-point of the sons of the old aristocracy, the class to whom government was second nature? Among the Oxford undergraduates the battle for the new political ideals was keenly fought, and the issue uncertain. They flocked into the doors of the Union all the more eagerly when they knew that the President of the Union, young William Ewart Gladstone, was going to speak.

For Gladstone was known to be a convinced Tory. Men smiled to remember that at Eton, when he was only sixteen, he had proudly said of himself: I am well aware that my prejudices and my predilections have long been enlisted on the side of Toryism. But they knew, also, that he was an unusually serious and passionately ambitious young man, who excelled all his competitors in scholarship, and exerted an irresistible influence over the more distinguished undergraduates of his time. He counted among his devoted friends many young noblemensuch as Lord Lincoln, the son of the Duke of Newcastlealthough he himself was of middle-class origin. His father was a Liverpool merchant, who had amassed considerable wealth, and was the owner of coffee and sugar plantations in the West Indies. It was known that he had been counted among the friends of the great Canning, who had died so suddenly four years earlier, and who, in 1822, had been waiting in his house for the ship that was to take him to India as Governor-General, when Castlereaghs suicide had opened for him the path to the Ministry, and to a political career which, brief though it was, had revolutionized European politics. In the spirit of Canning young Gladstone, speaking in the Union, had defended Catholic Emancipation, which after many years of conflict had been passed in 1829. But in the spirit of Canning he was a declared opponent of the electoral reform advocated by the Whigs, and in the Union he had introduced a motion in which he described it, with youthful dogmatism, as not merely a complete alteration of the form of government, but as destructive of the very foundations of the social order. Naturally, all were eager to hear what he had to say.

Now the youthful politicianhe was twenty-one years of age was on his feet, facing his audience. He was tall and raven-haired, and those who had once seen him never forgot the great eyes, full of life and enthusiasm. He spoke in the keen, logical dialectic which Oxford taught her sons, in a voice whose resonance and wealth of modulation held the hearer spellbound. What the young Gladstone said in his forty-five minutes speech no stenographer recorded for posterity. But many of his listeners described, in after years, the impression which he had made upon them. When Gladstone sat down we all of us felt that an epoch in our lives had occurred, wrote one of them; and another, who afterwards became a bishop, declared that he felt certain, even then, that this young man would one day rise to be Prime Minister of England. But Lord Lincoln wrote to his father, the Duke of Newcastle, that so soon as a seat in any constituency under his control was vacant, he must offer it to no one but his friend William Ewart Gladstone. A man is uprisen in Israel.