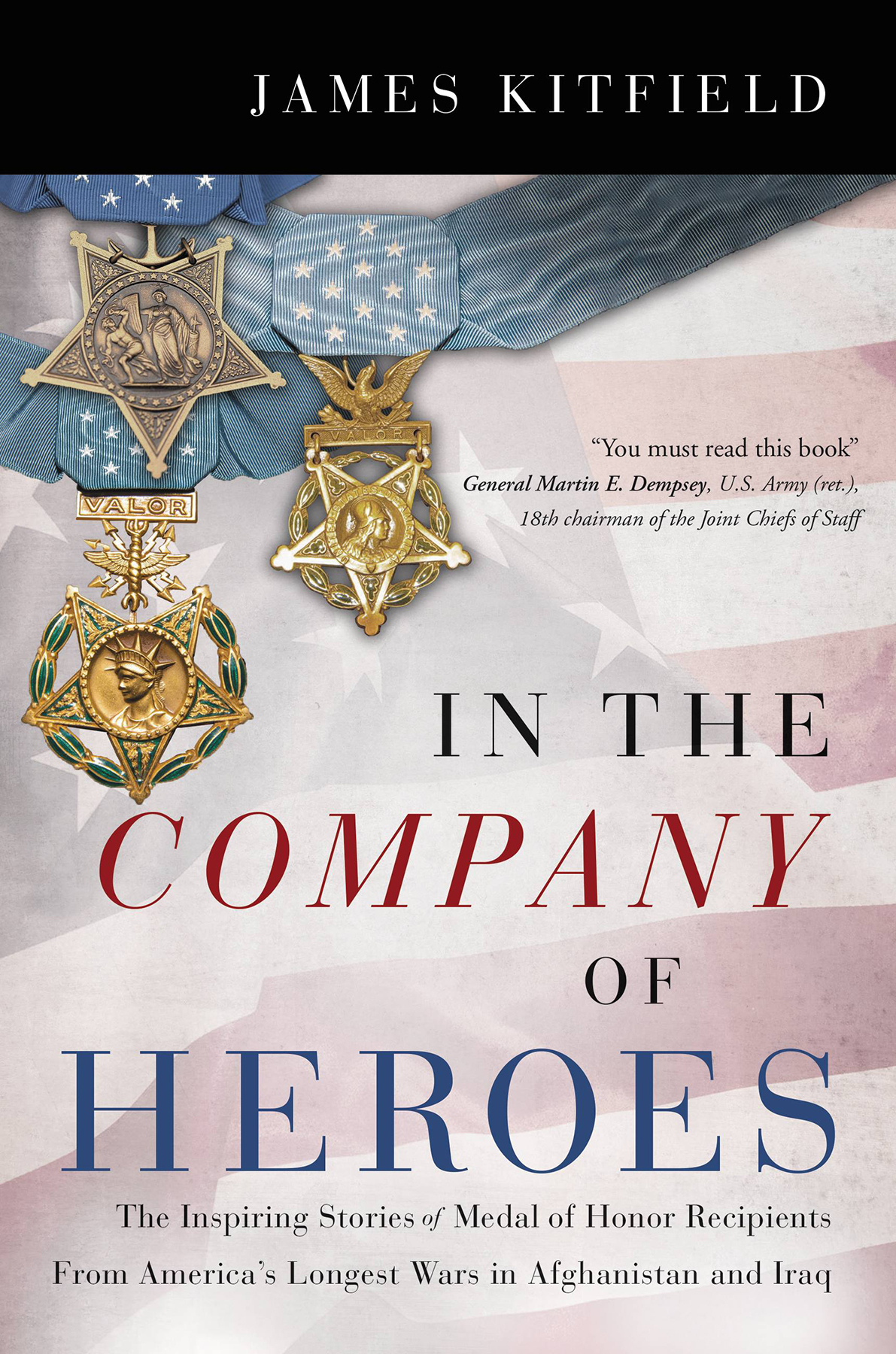

Copyright 2021 by James Kitfield

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Center Street

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

centerstreet.com

twitter.com/centerstreet

First Edition: August 2021

Center Street is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Center Street name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-1-5460-8579-9 (hardcover), 978-1-5460-8580-5 (ebook)

E3-20210811-JV-NF-ORI

Dedicated to the uniformed volunteers who answered the call and fought their nations longest wars after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks:

The New Greatest Generation.

On an unseasonably warm evening in mid-September 2018, a crowd of Naval Academy midshipmen in starched uniforms poured through the entryway of Dahlgren Hall. The cavernous Beaux-Arts structure was buzzing with excitement. The young midshipmen had been promised a Friday night of celebration and celebrity, with Patriot Awards to be given to Secretary of Defense James Mattis, Fox News anchor Chris Wallace, Senator Susan Collins of Maine, and former Tonight Show comedian Jay Leno. Yet the patriots many of the midshipmen most wanted to meet on September 15, 2018, were not celebrities or politicians, but rather members of the worlds most exclusive fraternity.

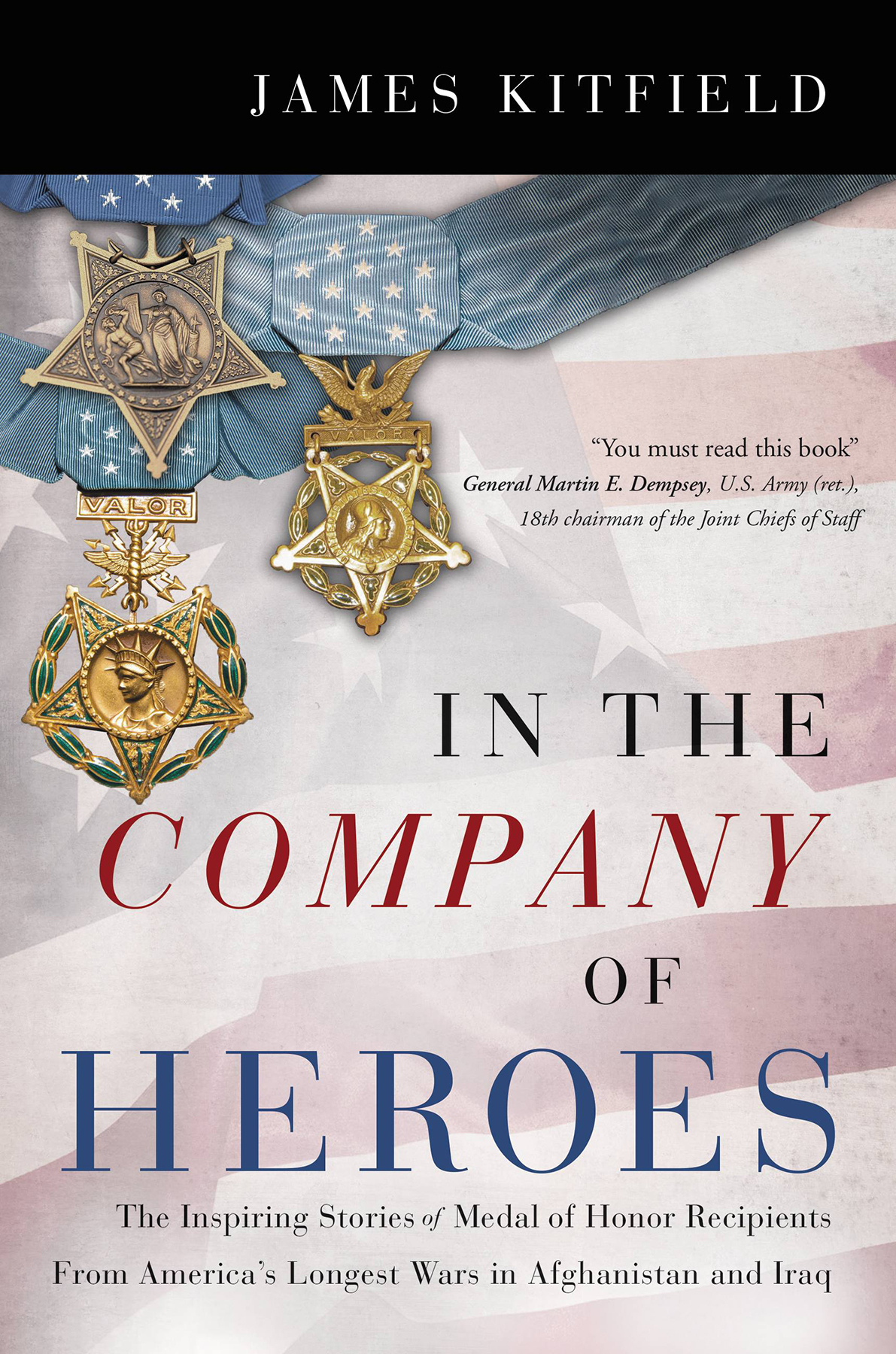

Admission into the Congressional Medal of Honor Society cannot be purchased with any currency other than valor. Of the only seventy-two then-living recipients of the Medal of Honorthe nations highest military award for bravery in combat above and beyond the call of dutyfully forty-four attended the annual meeting in Annapolis, the societys first-ever event at the service academy. Each of them had emerged through a painstaking process that begins with a recommendation from their chain of command or Congress, is subjected to months of intense scrutiny and investigation by a Decorations Board and must be approved by the Pentagons head of Manpower and Reserve Affairs, the chief of staff of their particular armed service, the secretary of defense, and ultimately the president of the United States.

Besides the Patriot Awards dinner, the Medal of Honor Societys four-day convention included a town hall forum and autograph session with the public, a private lunch with Naval Academy midshipmen, a parade ground review of the academys marching brigade, and a Navy football game. At every stop and venue, crowds gathered close to these heroes to be reminded of something essential about the American character. The extraordinary qualities and principles they embody are often lost in our celebrity culture and in the self-absorption of social media, or they are discounted in an endless news cycle driven by sensational headlines and clickbait. Yet these men are nevertheless a true reflection of the parents and communities across the nation that raised them, and especially of the many nameless men and women in uniform who served by their sides and watched their backs. Their stories recall the broad sweep of history that has seen generation after generation of Americans called to duty during times of war.

That trumpet sounded even before President Abraham Lincoln first established the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1862 to recognize such noncommissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldier-like qualities during the present insurrection. In 1863 the medal became a permanent military decoration available to all in uniform, including commissioned officers. That expansion came in time to honor Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. On July 2, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, Chamberlain defended the left flank of the Union army from repeated Confederate attacks on Little Round Top. When his 20th Maine was decimated by casualties and nearly out of ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a bayonet charge down the mountain that broke the Confederate lines and helped secure victory in the decisive battle of the Civil War.

So it has been with the other 3,526 Medals of Honor awarded since it was established, a constellation of heroism delineating a nation born of high ideals, yet defended and sustained only through martial will and bloody sacrifice. The arc of Americas ascendance from a fledgling democracy ultimately to an unrivaled global superpower is also revealed in that accounting.

There were 1,523 Medals of Honor awarded during the war to preserve the Union, and 426 for the Indian campaigns as the country expanded westward in the name of Manifest Destiny. The colonial-era wars of the late 1800s and early 1900s (the Spanish-American War, Philippines War, Samoan campaign, Chinese Boxer Rebellion, and Haitian and Dominican campaigns) produced 268 Medal of Honor recipients. The U.S. entry into World War I eventually led to 126 Medals of Honor being awarded, notably to include Sergeant Alvin York, a freckle-faced Tennessee mountaineer and would-be conscientious objector who became a legend for his actions in the Argonne Forest during the final offensive of the war. York was credited with killing 25 German soldiers, silencing 35 enemy machine guns, and single-handedly capturing 132 German prisoners.

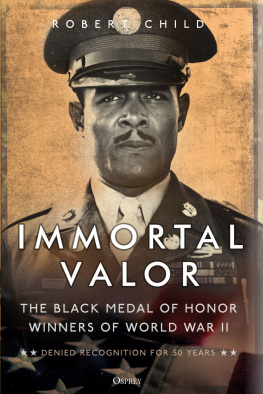

The Second World War fitted the United States for its superpower uniform, and the fighting in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters produced no fewer than 472 Medal of Honor recipients. They notably included Audie Murphy, the hardscrabble son of sharecroppers who lied in order to enlist in the Army at the age of sixteen, and at nineteen was credited with holding off an entire company of German soldiers. Murphy killed or wounded an estimated 50 German troops before suffering a severe leg wound, and then led a counterattack that decided the battle. Murphy would go on to become one of the most decorated soldiers of the war as well as a Hollywood actor and celebrity, though he never fully recovered from the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that plagues so many combat veterans.

Of the rapidly dwindling number of World War II Medal of Honor recipients, Hershel Woody Williams made it to the Annapolis convention in September 2018. The youngest of eleven children and raised on a dairy farm in West Virginia, Williams was rejected on his first attempt to enlist in the Marine Corps in 1942 because he was too short. Armed with a flamethrower, he would later single-handedly clear a network of reinforced Japanese pillboxes and machine-gun emplacements during the battle for Iwo Jima. He stood tall in receiving the Medal of Honor from President Harry S. Truman.

The Korean War that foreshadowed the long, twilight struggle of the Cold War between democracy and communism produced 145 Medal of Honor recipients. They included Japanese American Hiroshi Hershey Miyamura, who also attended the Annapolis reunion. Miyamuras wife had been incarcerated in an internment camp in the United States while he fought with the all-Nisei 100th Infantry Battalion in World War II. During the Korean War, Miyamura killed more than 50 Chinese troops, some in hand-to-hand combat, to give his fellow soldiers time to retreat and avoid being overrun or captured. He was wounded and spent the next twenty-eight months in a North Korean prisoner of war camp, later receiving the Medal of Honor from President Dwight D. Eisenhower.