Benjamin Whitmer would like to thank his wife, Brooky, and his children, Maddie and Jack, for putting up with his absences, and presences, during this project. Hed also like to thank Neil Strauss, Anthony Bozza, and Monique Sacks of Igniter Books, whose generosity and guidance could not have been more appreciated. And, of course, his agent, Gary Heidt, for sticking with him.

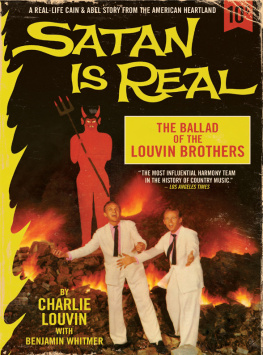

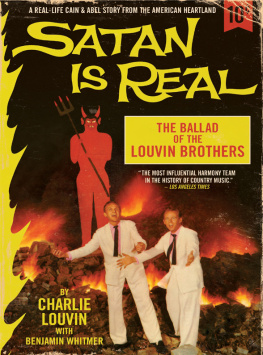

Born in Henagar, Alabama, CHARLIE LOUVIN recorded from 1947 to 1962 with his brother Ira as the Louvin Brothers. In 1955, they became members of the Grand Ole Opry and churned out thirteen hits on the Billboard country chart, including When I Stop Dreaming, Cash on the Barrelhead, and Knoxville Girl. Charlies solo career began in 1964 with the top five hit I Dont Love You Anymore, and he followed it with twenty-nine Billboard-charting singles and four Grammy nominations.

BENJAMIN WHITMER is the author of the novel Pike and a lifelong country music fan. He lives and writes in Denver.

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

My older brother Ira and I were finishing a stretch of shows, the last in Georgia, and we decided to stop by Mama and Papas place on Sand Mountain for a quick visit. Of course, wed barely got on the road before Ira reached under his seat and pulled out a bottle of whiskey, and he drank the whole damn thing on the drive. When I pulled up to the house, I stepped out on my side, and Ira just kind of poured himself out on his.

Mama was out in the front yard, and you could tell how excited she was to see us. She came running up to try to hug Ira, but he put his arm out to hold her off. He was wobbling on his feet, barely able to stand upright.

She knew what was going on. Mamas know everything. Aw, honey, she said, Why do you have to do this to yourself? She wouldnt even take Communion in a church unless they had grape juice instead of wine. She didnt use alcohol and she didnt understand anybody who did.

She should have known better than to say that, though. Nothing pissed Ira off like when somebody tried to put a little guilt on him. Aw, leave me alone, he said. I aint hurting nobody.

Youre hurting yourself, she said. Thats who youre hurting.

Yeah, well, I dont remember asking you, he said, and tried to light a cigarette. He was so drunk he couldnt even get his lighter to make a flame. Goddamn it, he said.

That whiskey dont do you no good, she said. It dont do nobody no good.

Finally, he got his lighter to work, and he poked his mouth at the fire to light the cigarette, but he missed.

Your fathers in Knoxville, she continued. I sure am glad hes not here right now to see you like this.

Ira threw the still unlit cigarette on the ground. Will you shut up, bitch?

I can guarantee you the fucking fight was on then. I beat the shit out of him right there in the front yard. He was lucky it was just words, too. If hed have touched her, Id still be in prison. Shit, if Papa was there, he might have killed him anyway, but I just kicked his ass all over the place. Then I stuffed him in the car, and we drove away.

I know you aint asleep, I said to him once we got on the highway. He was curled up on his side of the car, holding his busted face. Im only gonna tell you this once. If you talk to her like that again, Ill beat the shit out of you again. Ill do it every time. You can lump it or try to change it, but thats the way it is.

Oh, hell, I didnt mean nothing by it, he slurred. That was just that old whiskey talking.

That aint no excuse, I said. Nobody forced you to drink that stuff. And youd better not ever do it again.

Then I stopped talking and just drove, fuming. And I thought about that day, nineteen years ago, when I saw Roy Acuff driving past the farm in his big air-cooled Franklin. I thought it must be just about the best thing on earth to ride in a car like that. Now I was driving down that same road, a Grand Ole Opry star in an automobile almost as nice, and it felt like I was suffocating. Like I was being buried alive in it.

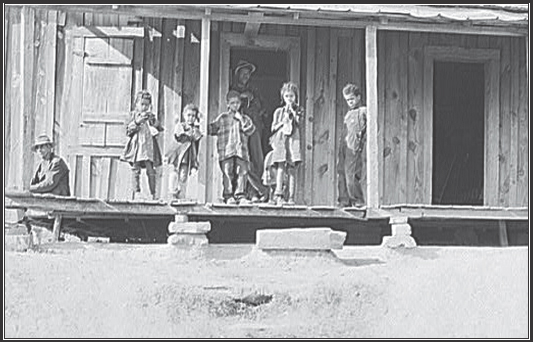

It was a warm afternoon in early autumn. The sky was clear blue and the sun was shining down, but it wasnt burning hot like it had been most of the summer. Papa was using the mules to pull a stalk chopper in one of the fields wed picked clean, cutting the cotton stalks into the ground. You couldnt till for the next crop of cotton unless you got rid of those stalks, and chopping them into the soil returned some of what the cotton pulled out.

If there was any work at all Papa could find to do with the mules, hed do it. He knew he had to keep them working if he wanted to make a living, just as he knew he had to keep his children working, too. He was a lean, hard, weather-beaten man, and even though he was only five foot, five inches tall, he had a way about him that made him look at least twice as big.

Even as hot as it was, he was wearing a long-sleeve shirt under his overalls, buttoned right up to the neck. I dont care if it was a hundred and five degrees in the shade, he wouldnt wear nothing else. Once that shirt got wet with sweat, hed look at anybody who had peeled off their shirt in the heat and say in a satisfied voice, Well, now Im cooler than you are, aint I? That was one of his beliefs, that once you got wet with sweat, your shirt would help you catch the breeze.

My brother Ira and I were in another field picking the last of the seasons cotton, pausing every few minutes to look over our shoulder for Roy Acuffs automobile to come tearing down the dirt road that ran by our farm. Ira was about sixteen and I was thirteen, and wed been waiting for the singer and fiddler since we pulled on our cotton sacks and walked out of the house at sunrise to begin the days work. There was nobody bigger than Roy Acuff to Ira and I.

Wed known that Roy Acuff would be driving past our house that day because Ed Watkins, who owned the mercantile store, had a radio in his living room. And the last Saturday, as soon as we got done in the cotton fields, Ira and I had run down to Watkins house and joined all the other farmers on his porch to listen to the Grand Ole Opry. There was about twenty-five of us gathered in the dark of that porch, and then twenty-five more in the yellow light of Watkins living room, leaning into his old radio.

Sand Mountain, Alabama, sharecroppers in 1940

Everybody knew what artists was going to be on at what time, and when their favorites came on, they stubbed out their cigarettes and moved inside to hear them, while the folks who were done listening to their favorites got up and came outside. Everybody on the porch was just as quiet as those inside. The radio was a little thing, not much of a speaker on it, and you had to really listen to hear what was going on. We did, and as soon as we heard Acuff being announced, it was our turn to go inside. We sat down on the rug, just as close to the radio as we could get.

Well, Acuff sang his songs, and we got up to leave. But just as we made it to our feet, we heard him start talking, announcing upcoming shows. When he got to the one next week at the Spring Hill School in Alabama, it felt like somebody had sucked all the air out of my lungs. Iras eyes were as big as pie plates and Ill bet mine were the same. He grabbed me by the arm quick and pulled me outside, away from the porch so we could talk.

Next page