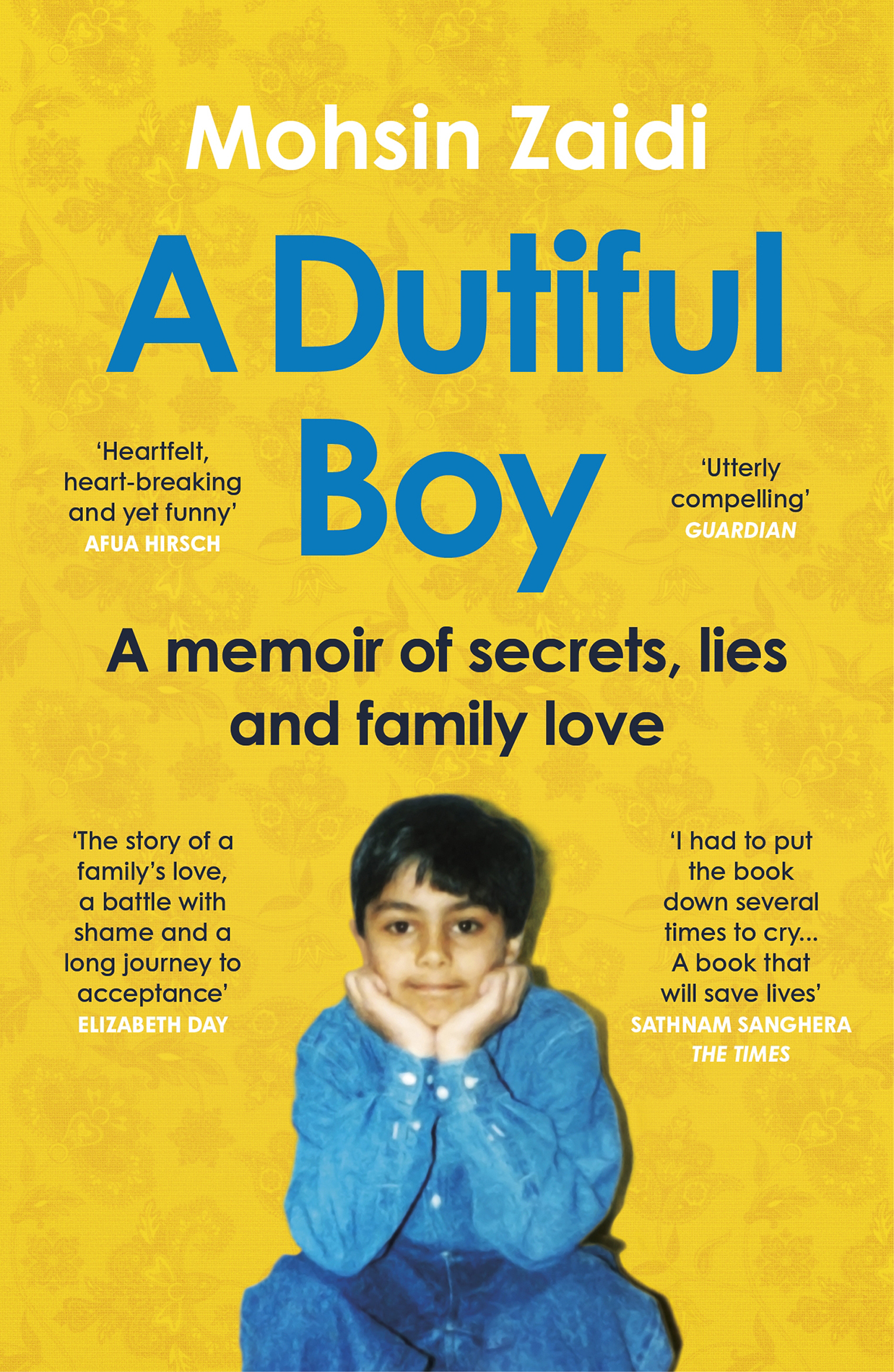

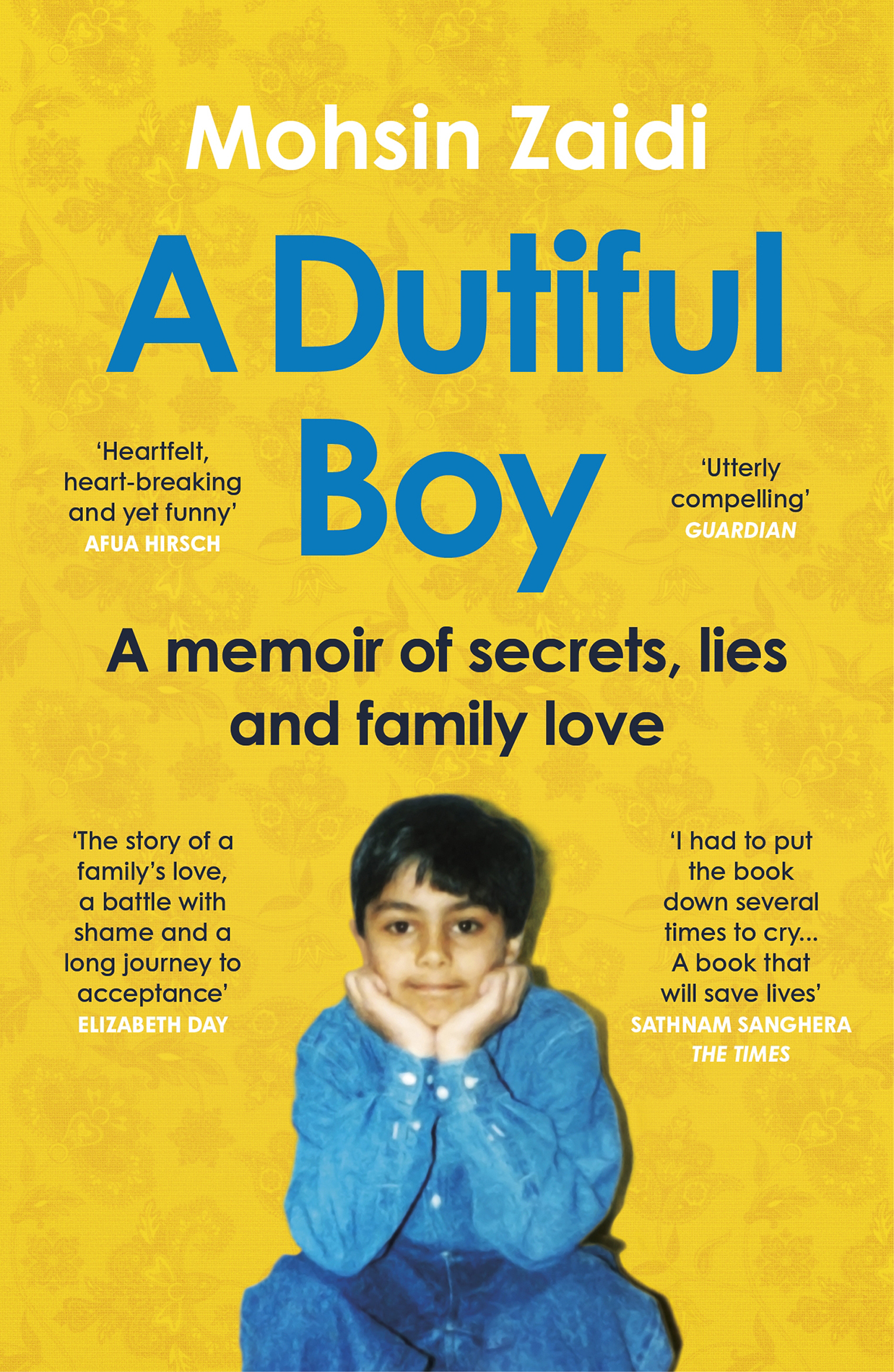

Mohsin Zaidi

A DUTIFUL BOY

A memoir of secrets, lies and family love

Contents

About the Author

Mohsin Zaidi is a criminal barrister at one of the top chambers in the country and represents clients in a number of high-profile cases. He has previously worked at a UN war crimes tribunal in The Hague and at the UKs Supreme Court. Mohsin is an advocate for LGBT rights, BAME representation and social mobility. He is on the board of Stonewall, the UKs biggest LGBT rights charity and is a governor of his former secondary school. Mohsin appears as a commentator on Sky News and has previously written for CNN Style, Bustle, Mr Porter and Newsweek. The Financial Times listed him as a top future LGBT leader, The Lawyer Magazine included him on their Hot 100 list, and Attitude magazine named him a trailblazer changing the world.

For Mamu Tier, the uncle every child should have. For my niece, Aya bear, in the hope she never needs me the way I need him.

And to every young person struggling with their identity. You are not alone.

PRAISE FOR A DUTIFUL BOY

It is about how the bonds of a loving family can transcend these thingssad, painful, warm, revelatory and utterly fascinating. I think we would live in a slightly kinder and better country if everyone read it

Mark Haddon, New Statesman

A profound meditation on the power of the human heart to transcend the contradictions of diverse cultures and create something new I couldnt put the book down It provides a lesson of acceptance for us all, and for the future of our multicultural society

The Guardian

Zaidi writes with an honesty that soars through this emotional rollercoaster of a memoir A Dutiful Boy delivers an intimate account of the anguish of one mans gay, Muslim coming of age story, and reveals something important about us all in the process

Afua Hirsch

It is deeply moving and profoundly important and it made me cry. If you liked The Boy with the Topknot by Sathnam Sanghera or Educated by Tara Westover, you will also love this book

Elizabeth Day

This is a story that needs to be read by everyone at a time when queerness, race, religion, and nationality are all being used as identifiers of being an other hope and love seep through these complex interconnectionsa hopeful story for many of us and one that needs to be heard. Now more so than ever before

Bad Form Review

A remarkable memoir an incredibly moving read. I had to put the book down several times to cry its a book that will save lives

Sathnam Sanghera

A true act of bravery Zaidis memoir is the identity narrative we need today. It confronts race, sexuality, faith, class, education, and mental health with extreme bravery and searing honesty as heartbreaking and profound as it is brimming with humanity, insight, and ultimately, hope. The world is a better place for having this memoir in it

Bustle

Heartfelt, emotional and really funny this book is very candid and it really educated and entertained me

Russell Tovey

Authors Note

The names and other identifying features of some people, places and events have been changed or merged in order to ensure that they are not identifiable so as to protect the privacy of individuals. This is a story based on memories of my experiences.

Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.

James Baldwin, 14 January 1962

Prologue

Her promise to meet him was only to placate me. It was hollow like our love had become. For ten years my mum had resisted. Fought against the idea as though she were holding off an army at the castle gates, and yet, here we were. A day I thought would never come. The drawbridge about to lower.

In battle, are you ever really ready for the white flag? In the moment, the focus is on the fight, so when surrender comes, the impact of it might leave you dumbfounded. But my plan had worked. Id played the long game and won. My heart didnt jump for joy or skip a beat. It lay inert and heavy in my chest.

My boyfriend and I would visit her and my dad at their home. A home from which it felt like so much of me had been exiled. Now, though, we would both go there to eat Pakistani food, cooked with her hands, with her history. Tastes from a faraway place to usher in an equally foreign concept.

My parents lived in a London suburb six stops east from Mile End on the Central Line. Those six stops were almost as familiar to me as the family home itself. Usually, I travelled alone and, at each stop, a part of me would fall away. At Stratford, I would forget what they had said to me. At Leyton, I would discard what they had done. By Leytonstone, Id put down the anger I felt towards Islam, dear to them and once so dear to me. At Snaresbrook, Id suppress my anger towards them. Then South Woodford, the penultimate stop. Thats where I would leave behind what I cherished most of all: my love for him. To take it with me would have been to disrespect, to demean it.

On this day, though, no part of me would be left behind. Not my love for him and not him either. Not his whiteness or the sharp blue of his eyes. If only I could dim the bright blue, which I loved so much, just for that evening. Make him smaller, moulded to fit neatly into their closed hearts.

Hours before we left, I lay on the bed feeling as blank as the ceiling I stared at. I couldnt do it, I told him. As I spoke cracks formed in my numb veneer, beneath it a seething rage. I told him I was sorry. And I was sorry. I was desperate to go through with it, but consumed by anger towards her, at myself and at the rules that had built a wall between us.

But then we were on our way, on a train heading for the unknowable. I held on to him more tightly as we got closer, for once hanging on to those things I had become so accustomed to leaving behind. We stood outside the house. Two men. My dad opened the door. I asked him where she was, and his frown made my heart sink.

PART ONE

1

My dads back was shredded and covered in blood. He had done this to himself. In front of me. I was seven. On the first nine evenings of the ten holiest days in the Shia Muslim calendar, my family and I would join the rest of our community at mosque, separated by gender, to beat at our chests with our hands. Standing in a wide circle under fluorescent tubes emitting a cheap, bright light, the most impassioned beaters would huddle at the front, topless, in the hope of inflicting just a little more pain. Bodies leaning back, hands raised high in the air, held there for a moment to gather momentum, then whipped down onto reddening brown torsos. Perfectly in sync with one another and with the Urdu words that rushed out of my jolted lungs. The methodical sound of skin slapping skin, escalating in my head and urging me to beat harder. But on the tenth day, in the car park of the mosque located just off a busy east London road, the grown-ups would use blades rather than hands.

My dad, who would do anything for his faith, gripped a black handle that fastened together three small chains connected to long silver blades. They glistened in the light, like a childs plaything. I gripped my little brothers hand, the two of us standing with other spectators. Members of St Johns Ambulance stood by, watching in disbelief, unable to rationalise what they were seeing. I was more enthralled by their reactions than those blades. Those I had seen before; the disapproving shock on these white faces I had not. They seemed scared but they had nothing to be scared of. My dad, fiercely devout, might do this to himself but he would never hurt anyone else. They blinked each time the knife struck skin, as if the pouring blood had splattered into their eyes. I stared at my dads back as he screamed. It was an emotional shriek, not a pained one, followed by another and another and another. Blood flying through the air, landing on peoples clothes and my face, staining my memories red. His eyes were shut as he continued to rip apart his back. Crimson streams traced lines down his torso, towards his legs. He looked in my direction. I do this for you, my son, and one day you will do this for me, he said without a word. Among the clattering of blades, I felt a sense of excitement, a sense of belonging to a small group of only the most devout Shias, those closest to God. A belonging that would grow stronger as I grew older. Strong enough that, one day, I too could shed blood and live.

Next page