The Obsession

Copyright 1973 by Meyer Levin

All rights reserved

Published as an ebook in 2014 by Jabberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

Cover design by John Fisk.

ISBN 978-1-625670-64-9.

THANK YOU FOR READING

This ebook has been brought to you by JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc.

Did you enjoy this JABberwocky ebook? Please consider leaving a review! To see what other ebooks we have available, visit us at http://awfulagent.com/ebooks/.

Help us make our ebooks better!

Wed love to hear from you, whether it's just to say how much you liked it, if you noticed any errors or formatting issues, or if you have any other comments about this title. Send us an email at .

Sincerely,

The JABberwocky Team

ALSO BY MEYER LEVIN

NOVELS

The Reporter

Frankie & Johnnie*

Yehude

The Golden Mountain

The New Bridge

The Old Bunch*

Citizens*

My Father's House

Compulsion

Eva

The Fanatic

The Stronghold

Gore and Igor

The Settlers*

The Harvest*

The Spell of Time*

The Architect

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL WORKS

In Search*

The Obsession*

*available as a Jabberwocky ebook

We do not know if we live in apathy or terror, in conspiracy or moral incompetence.*

N ORMAN M AILER

*New York Sunday Times Book Review, March 11, 1973

1

IN THE MIDDLE of life I fell into a trouble that was to grip, occupy, haunt, and all but devour me, these twenty years. Ive used the word fall. It implies something accidental, a stumbling, but we also use the word in speaking of falling in love, in which there is a sense of elevation, and where a fated-ness is implied, a feeling of being inevitably bound in through all the mysterious components of character to this expression of the life process, whether in the end beautifully gratifying, or predominantly painful.

In my fall, too, there lurks the powerful sense of the inevitable. Through the years of this grim affair it has always seemed that the process had to come, that it was the inevitable expression of all I ever was, all I ever did, as a writer and as a Jew; that it was in itself virtually artistic in its construction, its hidden elements, its gradual summoning up and revelation of character both in myself and others, and in its exposition of social forces.

The long trouble contained confrontations, even a public trial, and at various points I told myself it was over with, it had to be ended, that I was ejecting the entire cancerous growth from my psyche. But to every human being there remains, I believe, one final, ineradicable motive. This is the need to unravel the three-threaded intertwinings of fate, manipulation, and ones own will. What happened to me? is our unrelinquishable puzzle. Exactly how did it, how could it have, come about? we demand. Was all this from within myself? one asks, or from outside? Was there some hidden, secret force working on me so that no matter what I did through the normal ways of society I could not prevail?Ah! paranoia!But if I trace back and find that there really was such a force?Witches! Demons! The conspiratorial view of history!

Four times I sought to trace it all out within myself, through analysis. Before beginning to write this account, a year ago, I was in session with my fourth analyst. I was telling of the courtroom trial that had taken place, already some fifteen years back, and of an incident at the close of the trial, which involved my sister Bess in Chicago. All these fifteen years I had freely told this incident. Now as I came to the key words, I couldnt utter them. I was suddenly choked with anguish. I turned my head away, trying to regain self-control.

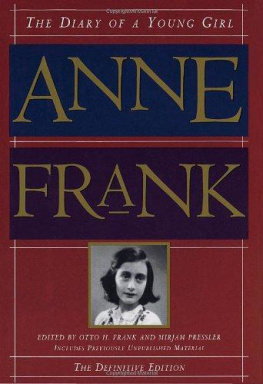

The case in court had arisen from my difficulties over The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank. Continuing from my war correspondent experiences my intense absorption with the Holocaust, I had helped Otto Frank to secure publication for the Diary in English, and had dramatized it. Mr. Frank had come to New York, to see to the authenticity of the staging, but at that point the prominent playwright Lillian Hellman and her producer, Kermit Bloomgarden, had persuaded him, he told me, that as a novelist I was no dramatist, that my work was unstageworthy, that it had to be discarded and another version written.

From the start I had strongly suspected that some doctrinaire formulation rather than pure dramatic judgment had caused Miss Hellmans attack on my play, and after the substitute work written under her tutelage was produced, I became convinced that I had been barred because I and my work were in her political view too Jewish. The Broadway play omitted what I and others, including several serious critics, considered essential material in the Diary. But also, while my work had been flagrantly smeared as unstageworthy, the Broadway play proved identical in staging, with important scenes startlingly parallel to mine. The whole affair increasingly appeared to me as a classic instance of declaring an author incompetent, in order to cover up what was really an act of censorship. And in this, not only I, but Anne Frank was involved, as well as the public. Yet because of rampant McCarthyism, I could not then make public what I saw as the real issue: doctrinaire censorship of the Stalinist variety. Even at the trial I did not bring this issue out, for fear of supplying material to McCarthys inquisitors.

Continual requests, mostly from noncommercial groups, for permission to perform my version were refused by the Diary owners. Appeals from literary personalities, community leaders, and even a massive petition from the rabbinate had failed, and I had finally gone to court. I won a jury verdict awarding me a high sum for damages, but as my opponents, with virtually unlimited funds at their disposal, kept up the costly litigation, I accepted a lesser settlement, so long as it assured me moral victory. Only to find that the play remained suppressed.

Thus, I was not freed from the problem. Here I sat, seven books, fifteen years afterward, face averted from Dr. Erika.

Let it come, the analyst said unobtrusively, meaning the weeping. As a knowing repeater in analysis, I was aware that this was to be counted as a breakthrough; only once before, quite long ago, with the first analystalso a womanhad I wept. But that analysis had begun years before the trouble, and the weeping then had come because of a clear, stark horror, the suicide of Mabel, my divorced wife. Then the source was primary. The analyst led you softly to the abyss, and you looked down in, and wept. An achievement, a natural reactionyou were human, you must feel released.

This time also I had been telling of a deathmy brother-in-law, his name Meyer, like mine. (Ah, identification! Ones own death! Weeping!) On the last day of the trial in New York, as I sat in the courtroom hearing my lawyer make his summation, a message came from my sister Bess in Chicago saying that Meyer had died. His third heart attack.

I couldnt possibly leave the courtroom, whispered my counsel at the table. Think of the effect on the jury if I walked out on our own summation! I must be here for the judges instructionthat was mandatory. Nor could we ask for a recess at this point; our case was difficult. If the judge explained the reason, it would sound like a play for sympathy. After the jury went out the next morning, I could leave for Chicago.