Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright Hanne rstavik, 2020

Translation copyright Martin Aitken, 2022

First published by Forlaget Oktober AS, 2020

Published in agreement with Oslo Literary Agency

First Archipelago Books Edition, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Ebook ISBN9781953861450

Archipelago Books

232 3rd Street #A111

Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.archipelagobooks.org

Distributed by Penguin Random House

www.penguinrandomhouse.com

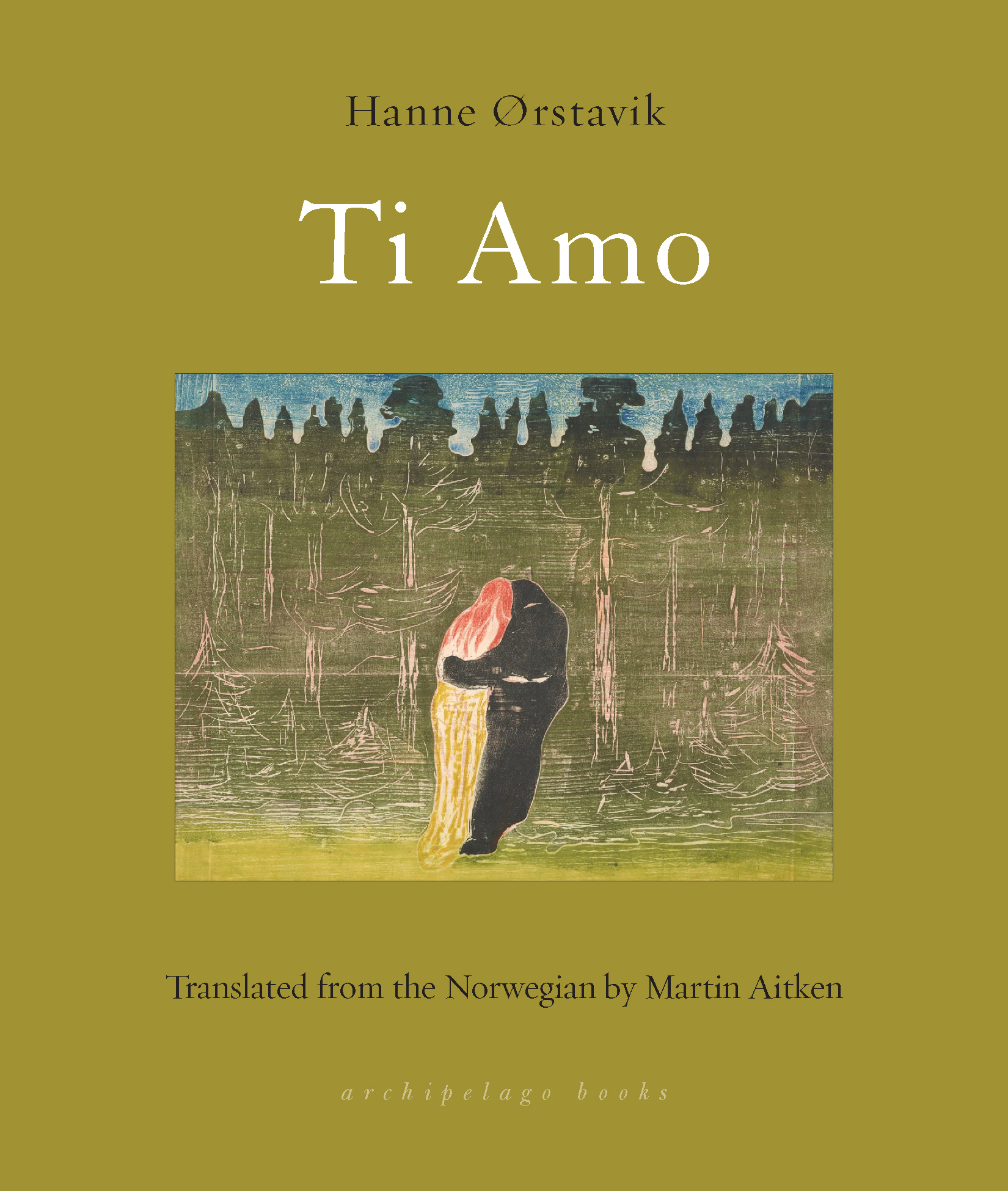

Cover art by Edvard Munch

Book design: Gopa & Ted2, Inc

This work is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature.

Funding for the publication of this book was provided by a grant from the Carl Lesnor Family Foundation. This publication was made possible with support from Lannan Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad)

a_prh_6.0_140847925_c0_r0

Contents

T I A MO

I LOVE YOU . We say it to each other all the time. We say it instead of saying something else. What would that something else be? You: Im dying. Us: Dont leave me. Me: I dont know what to do. Before: I dont know what Ill do without you. When youre not here anymore. Now: I dont know what to do with these days, all this time, in which death is the most obvious of all things. I love you. You say it at night when you wake up in pain, or between dreams, and reach out for me. I say it to you when my hand finds your skull, which has become small and round in my palm now that your hair is almost gone, or when I stroke you gently to get you to turn over and stop snoring. I love you. Once, I would reach out in the night to touch your skin, to place my hand on your back, your stomach, your thigh, anywhere at all, and thered be connection, contact. And in that feeling of skin and warmth, something small and without language, something perhaps undeveloped in me, a newborn part, could sink down to sense the base of night, return home, or arrive. I love you. But you are no longer in your body, I dont know where you are. Awash in morphine, you drift in and out of sleep or languor, and we do not talk about death, I love you, you say to me instead, and reach out for me from the bed on which you lie through the days, fully dressed, writing on your phone, writing a novel on that little screen, two or three lines at a time before you drift into sleep again, and I let go of the door frame and step towards you and take your hand and look at you and say: I love you, too.

Language difficulties

The relationship to reality is what matters,

wrote Birgitta Trotzig in the mid-seventies when I was six or seven years old. I saw her one autumn at the book fair in Gothenburg, it must be ten years ago now, probably more; we were both on our way from the Stadsbiblioteket to the main site, she on the opposite sidewalk in a long black skirt, limping slightly, from hip troubles, perhaps. A year or two later, I read that she was dead.

When it comes to what really happens to me, in life, Im struck into silence. Silence! Stop sign zone border! It becomes almost physically impossible for me to as much as register facts, dates at least periodically. The real-life event hits me, massively burdensome and complicated, overwhelmingly intangible and transforms all speech, any form of direct articulation, into an unreal rustling of leaves.

When did it all start? When did you actually become ill? Were you already ill that January we were in Venice, nearly two years ago, and you vomited and pulled out of your business dinner and the talk you were supposed to give? Three days later, we went to India. Were your cells already then frenetically dividing as we sat in the darkness, in a rowboat on the river, and watched the funeral pyres on the ghats of Varanasi?

Were you already ill then, in January 2018? The next time was June. Id been at the book festival in Aarhus and we met up in Copenhagen. Wed rented an Airbnb on Islands Brygge, with a pull-out couch and the tiniest of bathrooms, a second-floor flat with a little balcony from where we could see the mouth of the harbor, the canal on the right. We met up on Saturday. I came in on the train, youd taken a flight and were already checked in when I got there, youd picked up the key from the host, whod told us to say we were friends of hers if anyone asked. She was a singer, and we made up stories in which we were Norwegian and Italian musicians, I a cellist, you a violinist. But we didnt see anyone. The next day, we went out early and just walked, through the city center, into the northern quarters beyond the city lakes, streets wed never walked before, we veered left into Vesterbro, and then suddenly, as we got to Kdbyen, the old meat-packing district, you had to stop and hold onto the corner of a building. You couldnt walk another step. It was impossible to tell if you were exhausted or in pain, you were almost angry with yourself. We took a taxi back to the flat.

We ate outside on the balcony all three nights. You hadnt the strength to go out looking for somewhere. It was nice, we both thought so. In bed you sat up, bent double in the night, such was the pain in your back. Im not sure how much you slept, if you could even sleep like that. I kept waking up and youd be sitting there next to me, bent double. Only now I remember you werent well before that either, two weeks before, at that wine festival in Bordeaux. Youd been there years ago with a friend and so much wanted to go back again, with me, to amble about with a wine glass in a holder around your neck, pausing at the various tasting stations, trying the different wines and rinsing your glass in the little fountain before moving on to the next. We went to Bordeaux before I was due at the book festival in Denmark. Wed booked a room at a little two-star hotel, there were windows on two sides, one facing out onto a park, French windows extending to the floor, and we didnt eat out in Bordeaux either, despite you being so fond of eating out, we stayed in the room with wine and cheese, bread and couscous salad from the supermarket. You hadnt the energy. And in the night you were in pain. You hardly mentioned it.

From my point of view, something happened during the spring of 2018. It was as if the flame began to dwindle. The energy went out of you, and I thought it was to do with us. That wed gone into a slide and that living with you, my whole reason for uprooting to Milan, was now going to tail away, until there was nothing left but a bare minimum of energy, a minimum of intensity.

I was jealous of your pain, which mounted over the summer. Youd wander about at night in our dark, roomy apartment, moaning and whimpering. It never occurred to me that you could be seriously ill. I reasoned the pain was from keeping something inside, that you werent happy with me anymore and didnt want the life we were living, only you couldnt bring yourself to acknowledge it and tell me. That was what I thought. Sometimes I wondered if there was someone else, and would convince myself of it, that some other woman had become the object of your desires. For you were giving so little away, the signals you sent me were so unclear.