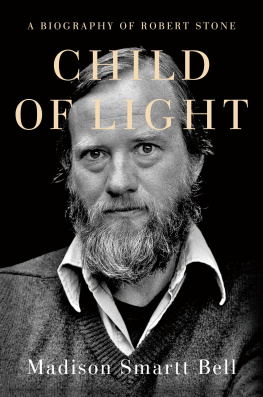

First Mariner Books edition 2021

Copyright 2020 by the Estate of Robert Stone

Introduction and part introductions copyright 2020 by Madison Smartt Bell

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-618-38624-6

ISBN 9780358505013 (pbk.)

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photograph Marion Ettlinger

eISBN 978-0-358-21214-0

v2.0221

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Lauren Wein and Pilar Garcia-Brown for helping the wheels turn smoothly, and to Janice Stone for her meticulous cataloging of the corpus of Robert Stones nonfiction. Thanks to Anna Young for rendering order out of the chaos of the raw materials of this book. Larry Cooper was the manuscript editor for several of Stones most important books (not to mention several of mine); to work with him on this volume was a boon.MSB

Introduction

All American novelists are embarked on a search for meaning; Robert Stone conducted his version of the quest in a style and within a structure uniquely his own. We assume too that our writers are products of their origins. Stones origins were obscure, his childhood difficult, his youth quite seriously dangerous. A weaker, less talented and intelligent person would not have survived those circumstances, much less prevailed in the way that Stone did, as a great artist and as a pellucid, unflinching observer and analyst of the time in which he lived.

The Homer Stone on his birth certificate was perhaps a convenient fiction. Born in 1937, Robert Stone was raised by his mother, Gladys Grant, a couple of generations before single motherhood would come to be viewed as a socially acceptable, even admirable, lifestyle choice. Gladys was an unusual and in some ways a redoubtable person, a cosmopolitan whose enactment of her independent spirit was many decades ahead of her time. She also suffered from progressively worsening mental illness, which meant that when Stone was a small boy she lost her job as a schoolteacher and the relative stability that went with it.

With his mother hospitalized, Stone was catapulted from a reasonably comfortable New York apartment to the orphans dormitory of St. Anns school on Lexington Avenue. After a few years Gladys was able to bring him home, though in fact they were sometimes homeless, in Chicago and in New York. At ten, eleven, twelve years old, Stone was a street urchin living by his wits, developing his first skills as a fiction writer by inventing stories to keep out of the clutches of Child Protective Services. In his middle teens he joined a street gang called the Saxons. New York youth gangs fought with knives rather than firearms back then. Some were killed, nevertheless, not only by steel but, increasingly, by heroin.

Expelled from his senior year at Saint Anns high school for a range of rebellious behavior, Stone joined the US Navy at age seventeen. During the three-year cruise, he continued his education as an autodidact, reading everything he could get his hands on, from Conrad to Kerouac. He also wrote some short fiction shipboard, and at the end of his enlistment, he was on his way to becoming one of the great writers of the late twentieth century. One might have called it a Horatio Alger rags-to-riches story, except that Stone, who in no way resembled any Alger hero, would have dismissed any such idea with scornful laughter.

Though he wore a cynical carapace, Stone was not really a cynic. His satirical bent, and the considerable anger that drives his most passionate work, comes from frustrated idealism. His frustrations had both a social and spiritual dimension.

After the navy, Stone attended New York University briefly, on a scholarship, which he lost because he could not manage to be both a full-time student and a full-time employee of the Daily News. He married young, and children came early; Stone was wont to call his children hostages to fortune, quoting Francis Bacon. He traveled with his wife, Janice, first to New Orleans, then to San Francisco to take up a Stegner Fellowship, awarded him on the basis of a few early stories, though hed never been anywhere near attaining an undergraduate degree. Wallace Stegner was an influence, and much more so Ken Kesey; Stone was for a time enveloped in Keseys charmed circle while somehow always managing to keep a certain ironic distance from it.

Experience with LSD and the early counterculture did much to reshape his mind. So too did a sojourn in Vietnam (as a journalist and observer), in the midst of the American war in that country. Stone had reached adulthood at the end of the 1950sbefore the opening of the doors of perception and the winds of revolution had begun to work their seismic changes on American culture and society. He was in those transformationsoften up to his neckbut never entirely of them.

His first three novels (A Hall of Mirrors, Dog Soldiers, and A Flag for Sunrise) were acclaimed as having captured the American zeitgeist of the periods in which they were set. The success of the third novel consolidated Stones position not only as an artist but as a social commentator to be attended to. He was never quite the sort of public intellectual that Hemingway had been and Norman Mailer very consciously tried to beif only because that role, for literary novelists, had been retired by the time Stone reached the stage. Still, in the five decades of articles and essays he published, before and after the end of the American Century, he was something like that.

Stones ambition and achievement as a novelist were both very great. He always had a hand on Americas heartbeat, as its rhythms altered from one phase to the next. The making of art was his first concern. Stone was a political novelist, a philosophical and sometimes a religious one. He was always a novelist of ideas, and the pieces in this volume are particular refinements of his ideassometimes as conclusions abstracted from novels he had already written and sometimes as explorations for novels yet to be composed.

During the last movement of A Flag for Sunrise, one of the principals (adrift in an open boat) has a hallucinatory dream in which a couple of sharks tell each other a sort of joke:

What is there? the shark asked his companion.

Just us, the other shark said.

Take away the bitter irony and it might be seen as the statement of a secular humanistone who believes in nothing beyond the realm of human interaction. Or as the same character says in the same sequence, we have nothing but each other.

Stone did espouse that point of view, but without (paradoxical as it may seem) being limited to it. Although his mother was not especially observant, Stone grew up in a Catholic world, raised and trained in considerable part by the Marist Brothers who ran Saint Anns orphanage and also the twelve-year school that was part of the institution. Though his years living in the orphanage were thoroughly wretched, a little later Stone went through a period of intense devotion. The reaction when it came was equal and opposite in direction. He was expelled from high school, not only for showing up half drunk but (worse in the Marist view) for tempting his fellow students down the path to apostasyas well as declaring his own. I felt like Luther or something, he said years later. I really thought I was a superhero.

Stones adult attitude to such questions, never entirely fixed, shifted around between the two extremes. I am not a believer in God, he told one interviewer I have been a believer in God. I am obsessed with the absence of God. I believe in that phrase from Pascal that says... Everything on Earth gives a sign of the divine presence. Everywhere we look there seems to be evidence of it. And it never yields itself to our discovery. And yet it seems to be everywhere. Or as in the Kabbalistic notions, it is as though God has separated himself forever and would have to be put together by gathering up all these items of light which is a virtually impossible task. That whatever that was, whether it was some kind of physical force, big burst, or blast, we have seen the last of it, and yet it has conditioned the way we feel and what we want for all eternity. I think we go without it, we go with this longing and with this kind of half hallucination that we are seeing it out there. We want it to be there.