Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my late brother, Robert Dunnavant, Jr., an outstanding journalist who profoundly influenced my development as a writer and as a man

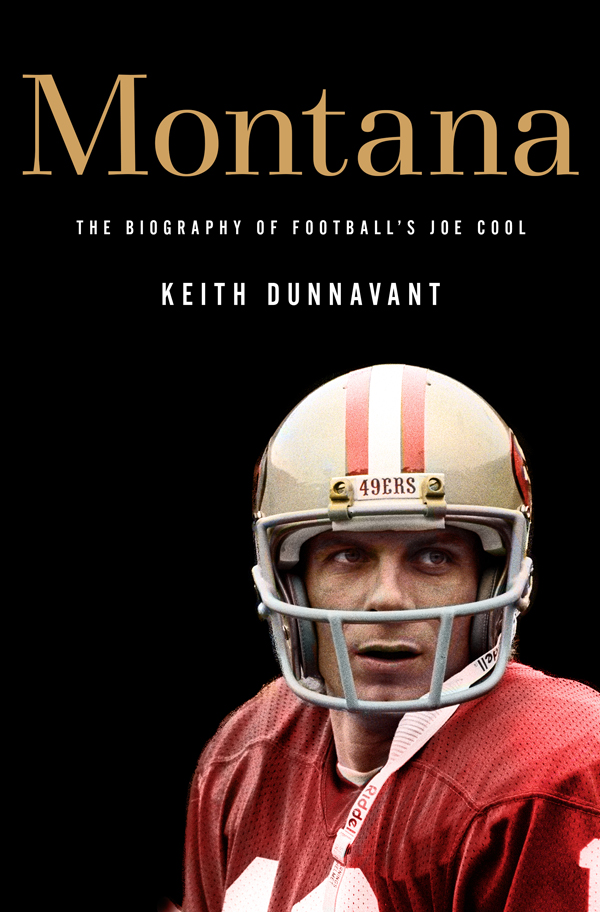

T HE QUARTERBACK GATHERED THE SNAP and rolled left, scanning the horizon for an open man. It was a beautiful day at Tampa Stadium, the air thick with September hope, when the Super Bowl tantalizes every team, even the woeful Buccaneers. It was a day Joe Montana would never forget.

By the time the San Francisco 49ers reached the third quarter of their 1986 season opener, headed for a decisive 317 victory over Tampa Bay, Montana owned two Super Bowl rings. He was the most efficient passer in the history of the National Football League. He was the man of countless heart-pounding rallies, including the memorable Cotton Bowl victory over Houston, when he overcame hypothermia, brutal cold, and a 22-point deficit to pull off the most stunning comeback in Notre Dame history. He was the man who sent Dwight Clark into the clouds to beat the Dallas Cowboys, turning a page in NFL history. He was Joe Cool. But he was not yet the man he was supposed to be.

One of the attributes that made Montana so tough to stop was his ability to get rid of the ball in a flash, often rolling left or right and contorting his body to send a perfect spiral soaring in the opposite direction, defying not just clawing defenders but immutable gravity. This time, as the quarterback drifted left, he could see Clark, his close friend, moving into the open to his right. In an instant, the window would close, and Montanas career had rested to a large measure on his skill in exploiting such small intervals of time and space. With the rush approaching, he twisted his body, cocked his right arm, and threw back to his right. Just as the ball drifted toward Clarks outstretched hands, he felt something in his body pop.

In a way he could not possibly comprehend, the quarterback had reached a turning point in his career.

Imagine Picasso without his blue period, Sinatra without the Capitol years, Cosell without Monday Night Football .

In September 1986, Joe Montana was not Joe Montana yet.

Not that Joe Montana.

Not yet.

T HE FATHER WAS A PUSHER. It all begins with the father, a Navy veteran who managed a local finance company on Main Street in Monongahela, a thriving blue-collar town near a bend in the big river, in the pulsating steel and coal corridor of western Pennsylvania. It all begins in that volatile cauldron of affection and ambition and vicarious thrill that so often goes terribly wrong. It all begins in a very dangerous place, where love so often turns to hate.

Joe Montana Sr., the descendent of Italian immigrants, played competitive sports in the service and was known around town as a decent backyard athlete who battled for every basket in pickup basketball games with teachers at the local high school. But every man approaches fatherhood in a reactive state, influenced, often unwittingly, by the lingering shadow of his own childhood. When I was a kid I never had anyone to take me in the backyard and throw a ball to me, he once said. Maybe thats why I got Joe started in sports. Sometimes its just that simple: a twinge of regret reverberating across the generations.

Every guy wants his kid to be a better athlete than he was, and Joe was no different, said family friend Carl Crawley Jr., who became the sons youth league football coach. Joe pushed and pushed and pushed Joey, because he wanted his son to have what he couldnt have and because he could see the kid wanted it.

The son, Joseph Clifford Montana, was born on a Monday, June 11, 1956, the year of Elvis, the Suez Crisis, and the Hungarian Revolution. His mother, Theresa, the daughter of Italian immigrants who had been lured to the new world by the great industrial expansion of the early twentieth century, eventually divided her time between homemaking chores and her employment at Civic Finance, where she kept the books down the hall from her husband. Joe Sr. had traded a career as an installer for the telephone company for the office job, which allowed him to spend more time with his family. The future Pro Football Hall of Famer was their only child. The Montanas were a tight-knit family, and in the years to come, in those adrenaline-filled days of the late 1960s and early 70s, when Joey was starring in three different sports for local teams, often traveling across Pennsylvania and beyond for youth-league and public school tournaments, she was almost always in attendancealternately manning the concession stand or cheering her boy on at the top of her lungs.

The son began his life in a modest two-story, wood-frame house on Monongahelas Park Avenue, a working-class street of tight contours and steep lots located just blocks from the central business district. The first hint of athleticism could be seenand heardwhen Montana was still an infant. He used to wreck his crib by standing up and rocking, his mother, who died in 2004, told Sports Illustrated . Then hed climb up on the side and jump to our bed. Youd hear a thump in the middle of the night and know he hit the bed and went on the floor.

Animated by dreamsencouraged by his fatherof someday becoming a professional athlete, young Joe began gravitating to the front porch at the end of the workday, ball in hand, waiting for his dad to arrive home so they could continue his athletic education amid the creeping late-afternoon shadows. Even when he was exhausted, the father always made the time. It didnt take him long to see that his son was gifted: fast afoot, able to throw farther and more accurately than other kids his age, capable of sinking a jump shot from long range. It didnt take him long to start investing a measure of his own self-esteem in his sons budding athletic career.

The elder Montana was the first to school him in the fundamentals of football, basketball, and baseball; the first to try to hone his raw talent; and the first to cultivate the competitiveness that would prove central to his success. Sometimes he taught by example, challenging the son to furious games of one-on-one in which he grabbed pushed [and] threw his elbows. Sometimes the pushing was tactical, like dangling a tire from a tree limb and making sure the son fired a certain number of tight spirals each day, so he could develop his arm. (Like many other Catholic boys across the land, he imagined himself as Notre Dame great Terry Hanratty, quarterback of the 1966 national champions, leading the Fighting Irish to another victory in the House that Rockne built. The father and son rarely missed an Irish game on the radio, and frequently watched the Sunday television replays.) Sometimes it was strategic, like fudging the paperwork so the eight-year-old could play nine-year-old midget league football. Even though he was a year younger than all the rest, the skinny kid with the closely cropped blond hair and the earnest blue eyes was immediately recognized as one of the best players, so naturally, he became a quarterback.

Unlike many of his teammates, he did not approach the game as an outlet for his boyish aggression. The chance to hit somebody was not what made him tick. A rather timid player who tried to avoid contact, he earned playing time by the projection of his superior athletic skills and a widely admired competitive streak. Even then, the coaches and players could see how much he hated to lose. Childhood teammate Keith Bassi recalled, Joe thrives on competition. He lives for it.