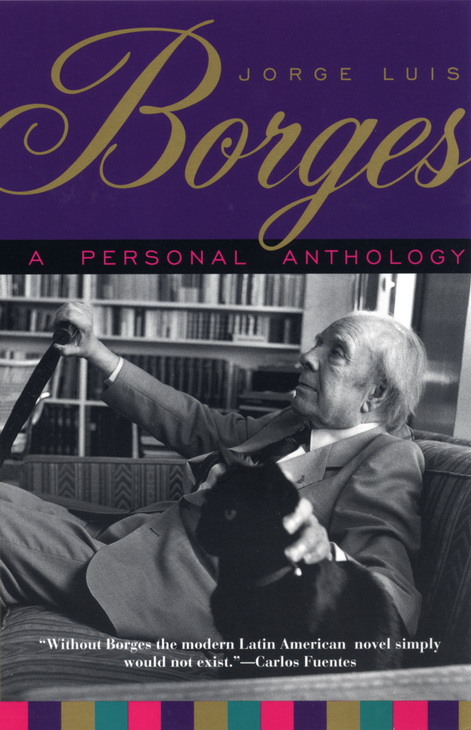

A PERSONAL ANTHOLOGY

Also by Jorge Luis Borges

Published by Grove Press

Ficciones

Jorge Luis Borges

A PERSONAL ANTHOLOGY

Edited and with a Foreword by Anthony Kerrigan

GROVE PRESS

GROVE PRESS

NEW YORK

Copyright 1967 by Grove Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Originally published as Antologia Personal , 1961 by Editorial Sur, S. A., Buenos Aires

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 67-29764

ISBN 978-0-8021-3077-8

eISBN 978-0-8021-9074-1

Cover design by Wendy Halitzer

Cover photograph Ferdinando Scianna/Magnum Photos

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Jorge Luis Borges is most poignantly and hauntingly interested in what men have believed in their doubt: Siddhartha, Josaphat, the Face of Christ; Duns Scotus, Averres, Berkeley, Hume; Judaism, its offshoot Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Idealism. His equivocation regarding heresies and dogmas renews them all, though he may be the unique evocative source of his own nostalgic non-belief in Belief or prescient belief in non-belief.

A fundamental theme always close to hand is his own identity. Like Don Quixote, he does not mind being a character in a book, so long as it is in the right book and not the wrong one. Don Quixote objected, in the Second Part of Don Quixote , by Cervantes, to appearing in the (spurious) Second Part of Don Quixote , by Avellaneda; Borges puts the question: Is not one single term repeated enough to break down and confound the history of the world? The right book for him to appear in, then, is the one by Borges. And no other. As for the present, he merely identifies himself as the one who swears he has not died.

(The identity of others concerned in the present book is dimly asseverated by their names at the end of each piece they translated. They are Americans and a Scotsman who have put into American and into English some of the thoughts Borges has had in various languageseven in Englishbefore he wrote them down in Spanish.)

Borges concern with history is unique. He is not taken with the grandiose Goethean-Romantic pivotal zeniths of Spenglerian cycles, or even with Unamuno's intra-history of dim daily existential Everyman routine, as he is moved by the epiphanies of racial and folk evolution. In the story of The Warrior and the Captive , he intuits a barbarian warrior's physic conversion to Rome as a city of light and order, and, conversely, of the Englishwoman's atavistic return to savagery in the vastness of the Argentine waste. Men leave off being wild beasts in one divine moment, or return to the earth to drink the blood of a slaughtered animal in another moment equally divine; enemies become blood brothers in the heat of battle, or a pursuer joins the prey in a paroxysm of blood identification ( Biography of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz ).

And as for History's periods, those Grand Ages of a Hero or of a God, they die out, period by period, in the physical death of a last survivor (as in The Witness ), and the world is the poorer.

History is also the epiphany of epigram: six feet of English earth for Ear aid Sigurdson; the odor of horses and of courage; I was proud of the men who had killed my brothers : these are the elements of what Borges calls true history, the vocabulary of The Modesty of History .

Among his several obsessions, Borges has counted a knife, The Knife. He is animated by the feel of it, he fictionally clutches it on behalf of others, he is atrociously aware of it, altogether frustrated, lying, unfulfilled, in his desk drawer, among his rough drafts and letters. A knife, moreover, the knife in his thoughts, is to kill; it was conceived and given form for a very special purpose. In addition, there is, in his verse, An impossible recollection of having died/Fighting, on some corner of a suburb. The Knife in his drawer should perforce fulfill its destiny; otherwise so much hard faith, such impassively innocent arrogance is rendered vain by non-use. An obsession with dying is proof of being alive; an obsession with a manner of dying, with being killed or killing, even more, is a creatively morbid concern with the diabolic importance of (someone's) being alive. This compulsive instinct is, perhaps, a true measure of Borges: it leads him to think, to assert, that if in the universein the entire history of the universe eventhere is or has ever been anyone who could be a duplicate of himself, then the meaning of all life, all lives, is altogether suspect.

The present collection is the attestation that no one is, ever has been, his replica. There is Borges and I, Borges and The Other, but there is, on the present evidence, no other Borges.

A NTHONY K ERRIGAN

Dublin, 1967

All the pieces presented here in English are complete versions of their originals in Spanish.

PROLOGUE

My preferences have dictated this book. I should like to be judged by it, justified or reproved because of it, and not by certain exercises in excessive and apocryphal local color which keep cropping up in anthologies and which I can not recall without a blush. To a chronological order I have preferred one of sympathies and differences. I have thereby proved, once again, my fundamental paucity: The Circular Ruins , which dates from 1939, prefigures The Golem or Chess , which are practically of the present. This paucity does not dishearten me, since it provides an illusion of continuity.

Croce held that art is expression; to this exigency, or to a deformation of this exigency, we owe the worst literature of our time. True enough, Paul Valry was able to write with felicity:

Comme le fruit se fond en puissance,

Comme en dlice il change son absence

Dans une bouche o sa forme se meurt

and Tennyson could write:

............................................................. and saw,

Straining his eyes beneath an arch of hand,

Or thought he saw, the speck that bore the King,

Down that long water opening on the deep

Somewhere far off, pass on and on, and go

From less to less and vanish into light.

verses which reproduce a mental process with precision; but such victories are rare and no one (I believe) will judge them the most lasting or necessary words in literature. Sometimes, I, too, sought expression. I know now that my gods grant me no more than allusion or mention.

Buenos Aires

August 16, 1961

J.L.B.

A PERSONAL ANTHOLOGY

DEATH AND THE COMPASS

Of the many problems which exercised the daring perspicacity of Lnnrot none was so strangeso harshly strange, we may sayas the staggered series of bloody acts which culminated at the villa of Triste-le-Roy, amid the boundless odor of the eucalypti. It is true that Erik Lnnrot did not succeed in preventing the last crime, but it is indisputable that he foresaw it. Nor did he, of course, guess the identity of Yarmolinsky's unfortunate assassin, but he did divine the secret morphology of the vicious series as well as the participation of Red Scharlach, whose alias is Scharlach the Dandy. This criminal (as so many others) had sworn on his honor to kill Lnnrot, but the latter had never allowed himself to be intimidated. Lnnrot thought of himself as a pure thinker, an Auguste Dupin, but there was something of the adventurer in him, and even of the gamester.

Next page

GROVE PRESS

GROVE PRESS