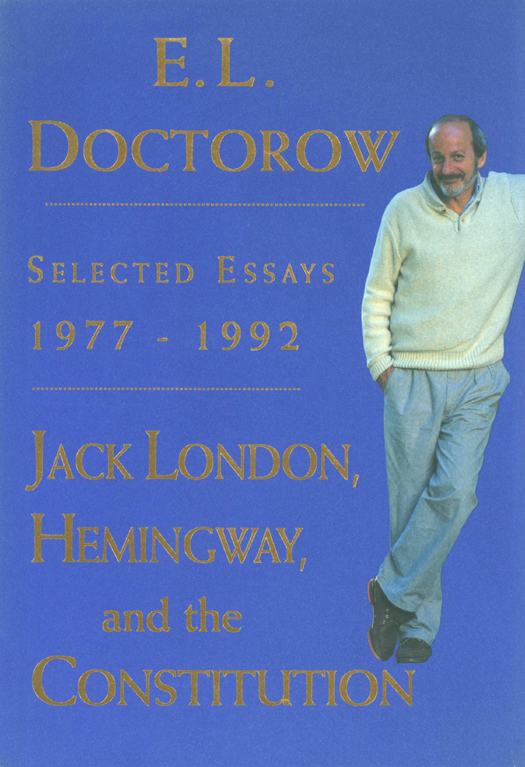

Copyright 1993 by E. L. Doctorow

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright

Conventions. Published in the United States by Random

House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto

Portions of this book have been previously published in Architectural Digest, Gettysburg Review, Harpers Magazine, The Michigan Quarterly Review, The Nation, New American Review, Playboy, and The New York Times Book Review.

Two Waldens was originally published in Heaven Is Under Our Feet, edited by Dawn Henly and David Marsh (Longmeadow Press, 1991).

and His Call of the Wild was originally published as the introduction to the Library of America edition of The Call of the Wild (Vintage Books, 1990).

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Bantam Books, a division of the Bantam, Doubleday, Dell Publishing Group, Inc., for permission to reprint the introduction by E. L. Doctorow to Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser (Bantam Books, 1982). Reprinted by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Doctorow, E. L.

Jack London, Hemingway, and the Constitution:

selected essays, 19771992/E. L. Doctorow. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79977-7

1. Title.

PS3554.O3J33 1993 814.54dc20 93-4179

v3.1_r2

Introduction

With one exception the pieces in this book were written because someone asked me to write them. Left to my own devices I will write fiction. I will choose the thrown voice and all its tropes. But when invited to write in my own voice for occasions not of my own devising, now and then, for one good or ignoble reason or another, I will do that.

The earliest of the pieces was written in 1977, the most recent in 1992. Im surprised to find that they have in common a kind of presumptive nationalism. They seem to concern themselves with American textsprinted or otherwise ingrained, those we recognize as ours and those we dont. Ive set them in what I hope is, roughly, the order of a thought process that goes: from the lives of some classic American authors, to the place of their work in the composition of our national character, to the ideas we can take from them as applicable to ourselves and our times, to our times as theyre constructed by our politics, to the states of mind we live in that we call our culture.

I cant be sure that another selection in another order wouldnt reveal the same underlying presumption. The writers I speak of (white male) made of themselves repositories of American myth, and the presidents I speak of (also white male) held mythic values no less vaunting. Ultimately, what politicians do becomes another kind of writingperhaps like Kafkas harrow, working its needles into the skin. But there is a real continuum insofar as those who make history write it, just as those who write it make it, an idea I give its fullest expression in the essay False Documents, and also acknowledge in a reflection on George Orwells mythbook, 1984, a superstatist American text, for all its nightmare European imagery.

But there is no text more central to our lives than our Constitution, which I treat here as Scripture, meaning a text that is read and studied and interpreted with statutory law, just as the scripture of Judaism, Christianity, or Islam is read and studied and interpreted.

And finally, as to American texts, there is the text of our cheapened dreams, our culture of popular song, the standards, as we call them, that sing in our heads generation after generation as a sort of urtext of the collective unconscious.

Where writers are not locked in history is Heaven, eventless Heaven. For all the variety of their subjects, these essays are necessarily spoken from the cultural milieu of the late, long cold war, which, one way or another, framed American intellectual life for almost half a century. I was a high school student in 1946 when Winston Churchill made his Iron Curtain speech at Fulton, Missouri. I published my first novel the year John F. Kennedy was elected president. Not that Im alonealmost all the writers publishing today came up in the cold war. In fact, just how long the war lasted may be realized by considering that, as to our literature, only one generation is still alivewriters in or verging on their seventieswhose working life has not been entirely circumscribed by it.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the breakdown of the Soviet Union, the war was declared over, but without any corresponding national sense of elation. If I were giving a State of the Mind of the Union address, I would describe us today as convalescing. Reality outraces apprehension, Melville says, speaking of the white whale, and so in spirit, in body, we are still to some extent suffering our cold war. This may have to do with the years of our denial. There were times when we were so inured to the wars dangers that we lived and worked as if it didnt exist. Children were born, went to school, married, and had children. Careers were embarked upon, the rhythms of private life tolled off the years. Yet the cold war was a fifty-year nuclear alert with two full-fledged nonnuclear clashes, Korea and Vietnam, fought in its shadow, and innumerable surrogate wars, covert subversions of foreign governments, coups, incursions, skirmishes, forays, international incidents, and nuclear weapons tests performed in its service. What is more, though the enemy to be contained was the Soviet Union, the creative animus of our warring mind was unleashed, to an astonishing degree, upon ourselves.

The penultimate piece in this book, James Wright at Kenyon, recalls the poet, my friend, during our undergraduate days in the American darkness of the late forties and early fifties. Time was to call us the silent generationas who, under the circumstances, would not be? An ideology of fear, sincerely or cynically broadcast by the politicians of the moment, devolved into a powerful civil religion with distinctly Puritan cruelties. Absolutist and Manichaean, it discovered and purged the designated subversive elements among us, not only with legal prosecutions where crimes had been committed, but with sworn oaths of loyalty, blacklists, and public rituals of confession and repentance before congressional committees where no crimes were supposed to have occurred other than crimes of thought.

That was the cold wars first phase. In its second phase, during the sixties, it took the lives of over fifty thousand of our young, and wounded and maimed tens of thousands more. Vietnam was the cold wars most absurd expression and attenuated rationale, and provoked a generation of students to arise in dissent and massively challenge its rigid orthodoxies. Their dissidence had the dynamic of a Reformation, the young rising against their elders dogma and its attendant culture and proposing another. At no other time since the Civil War has the country been so grievously torn.

In the aftermath of Vietnam, the generational survivors of the fifty thousand dead found themselves once again in an America unfazed, a land of pod people, the children behind them coming out studious, obedient, and smelling as clean as new car models. This was the third phase, akin to Counter-Reformationthe Rights chastisement of the ungrateful known as Morning in America.

In this final decade or so, with the mandate of a populace compliant with ruling circumstances, the last administrations of the cold war conflated its ideology with the capitalist principles of the nineteenth century. Deregulating industry, dismantling social legislation of benefit to anyone but their core constituencies, abjuring law enforcement where the law was not to their liking, and politicizing the courts, they distributed the enormous costs of the cold war democratically among all the classes of society except the wealthiest. The effect on our national standard of living was as a vampires arterial suck.